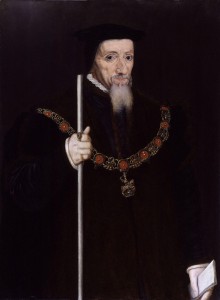

William Paulet wasn’t born into the powerful aristocracy. He came from Basing in Hampshire, born sometime between 1474 and 1488—even his birth date is a mystery!

William Paulet wasn’t born into the powerful aristocracy. He came from Basing in Hampshire, born sometime between 1474 and 1488—even his birth date is a mystery!

His family had connections, but nothing close to the powerhouses of the Tudor court. Unlike men like Thomas More or Thomas Cromwell, Paulet didn’t make his name by standing on principle or radical reform. Instead, he mastered something far more valuable in the Tudor world: survival.

He trained in law at the Inner Temple, which set him up for a career in administration, and he made a very smart marriage—Elizabeth Capell, the daughter of a wealthy Lord Mayor of London. It wasn’t the grandest match, but it gave him financial backing and key city connections.

His real break? He got in with Cardinal Wolsey, the king’s most powerful minister. And from there, he started his slow, careful rise.

Paulet first came to royal attention under Henry VIII, and he quickly started stacking up titles:

- Sheriff of Hampshire three times.

- A Justice of the Peace overseeing local law.

- Master of the King’s Wards, managing the wealth of young noble heirs.

It wasn’t glamorous, but it put him right in the heart of Tudor power.

By the 1530s, Paulet had become a trusted royal servant. He helped downgrade Catherine of Aragon to ‘Dowager Princess of Wales,’ proving his loyalty to Henry’s new order. And when Anne Boleyn fell in 1536, he was on the commission that sent her alleged lovers to the scaffold.

Did he believe in Anne’s guilt? Probably not. But in Henry’s court, belief didn’t matter—survival did.

Henry rewarded him with a peerage in 1539, making him Baron St John. He became a key financial administrator and by the 1540s was Lord Treasurer—a role he would hold for three more reigns.

Paulet had officially made it. But Henry VIII wouldn’t live forever—and his death in 1547 would bring one of the most dangerous transitions in English history.

When Henry VIII died, his nine-year-old son Edward VI took the throne. Paulet was named to the regency council—a huge moment for his career.

At first, he backed Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, the boy king’s uncle and Lord Protector. But when Seymour’s rule turned chaotic, Paulet sided with John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, instead.

And it paid off—he was made:

- Earl of Wiltshire in 1550

- and Marquess of Winchester in 1551

But Tudor politics were never stable. In 1553, Edward VI was dying. Northumberland tried to block Edward’s Catholic sister Mary from the throne, instead backing Lady Jane Grey. Paulet signed the letters patent putting Jane on the throne, but when Northumberland’s coup collapsed, he acted fast. While some stayed loyal to Jane and lost their heads, Paulet was one of the first to switch sides and declare for Mary. It was a classic Paulet move—he bent like the willow, not like the oak.

For many men, serving Edward’s Protestant government and then suddenly backing Mary, a Catholic queen, would be a problem.

Not for Paulet.

He kept his role as Lord Treasurer, and while others were being arrested, exiled, or executed, Paulet got to work fixing England’s finances.

One of his biggest tasks? Helping Mary fund her navy, which would later be key in England’s battle against Spain under Elizabeth.

When rebellion broke out, Mary made him Lieutenant General of London, putting him in charge of the city’s defences. And just like that, Paulet had survived yet another Tudor crisis.

But by 1558, everything was about to change again. Mary died, and Elizabeth I took the throne. By this point, Paulet was in his 80s—ancient by Tudor standards. You’d think he’d retire, right? Not William Paulet. He kept his job as Lord Treasurer and was so respected that Elizabeth once joked, "If my Lord Treasurer were but a young man, I could find it in my heart to have him for a husband before any man in England."

Even in old age, he held power until 1570, when his health forced him to step back. By then, he was in his 90s—a staggering lifespan in an age when most men didn’t live past 50. By the time William Paulet died on 10 March 1572, he had served:

- Henry VIII (Protestant, Catholic, and everything in between)

- Edward VI (Hardline Protestant)

- Mary I (Devout Catholic)

- Elizabeth I (Protestant again)

How?

Because he knew when to bend, not break. He never stood on principle—he stood on survival. He never made himself irreplaceable—he made himself essential. And when a regime changed, he never resisted the inevitable—he adapted to it. His own words sum it up best: "I was made of the pliable willow, not the stubborn oak." And in a world where conviction could get you killed, being flexible kept him alive.

Leave a Reply