Today we have a guest post from David Jacques, OBE, who is a garden and landscape historian. He discusses how the use of the garden changed during the Tudor period. Over to David...

Medieval gardens were for rest and recreation, but with the advent of non-fortified palaces not only they but also their gardens were increasingly designed to impress. In Britain that is seen with the Tudor dynasty and continued till William of Orange’s response to Versailles at Hampton Court.

Henry VII had spent 14 years in Brittany, safe from his Yorkist enemies, and the great castle gardens in neighbouring France such as at Anjers, Amboise and Blois were not far away. They were notable for their Italian-style compartiments and their galleries. Anxious to catch up as soon as he had the money to do so, Henry laid out some compartiments devised in ‘knot’ patterns at Richmond Palace and surrounded them with galleries. The knots were surrounded at ground level by posts and rails, with heraldic beasts atop the posts.

Henry VII had spent 14 years in Brittany, safe from his Yorkist enemies, and the great castle gardens in neighbouring France such as at Anjers, Amboise and Blois were not far away. They were notable for their Italian-style compartiments and their galleries. Anxious to catch up as soon as he had the money to do so, Henry laid out some compartiments devised in ‘knot’ patterns at Richmond Palace and surrounded them with galleries. The knots were surrounded at ground level by posts and rails, with heraldic beasts atop the posts.

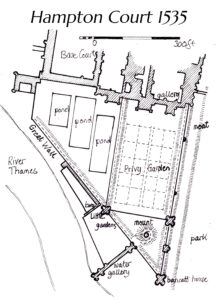

Henry VIII played tennis, jousted and hunted, leaving the diplomacy to Cardinal Wolsey. He added an ornamental orchard to the gardens at York House (he was archbishop of York), and bought and much enlarged Hampton Court, including adding a gallery overlooking knots and an ornamental orchard, so that it was grand enough to host the Holy Roman Emperor in 1522.

At Wolsey’s downfall in 1529, Henry took both these places. At York House (soon to be known as ‘Whitehall’) he erected more galleries and doubled the size of the Great Orchard that Wolsey had been making. Over time this became the ‘privy’ garden, set out in 16 quarters and with a forest of heraldic beasts on pillars (which had to be altered with each new queen).

Changes to Tudor Gardens

These changes were eclipsed by those at Hampton Court from 1530. There a triangular ‘new’ garden was set out between the gallery and the river Thames. Here Henry gave full vent to his taste for recalling chivalric ideals already seen with his jousting. The garden was dominated by a mount topped by a banqueting house, itself finished off with beasts and vanes. Between it and the gallery was the Privy Garden, again with a host of heraldic beasts, and to the west was an area with three ponds (which survive). The surrounding ‘great wall’ incorporated several battlemented turrets, giving the appearance of a fortified garden.

Towards the end of his reign Henry started Nonsuch Palace and ordered great changes to the gardens at Greenwich Palace. The great age of Tudor palace and garden making came to a halt with his death. Temporary banqueting houses were becoming a feature of diplomatic occasions, and a large canvas one was erected in Hyde Park in 1551 for the festivities upon the arrival of a French ambassador. This fashion was favoured by Queen Elizabeth, including the banqueting house of 1581 at Whitehall (later replaced by the present Banqueting House). They would often have ceilings painted to represent the heavens.

Elizabeth’s ‘progresses’ around the country encouraged the making of elaborate gardens, in particular that of her favourite, the Earl of Leicester, at Kenilworth Castle, which was ‘re-invoked’ in 2009. One of her rare extravagancies from 1572, on Leicester’s urging, was the north terrace at Windsor Castle, remaining in expanded form today. Later in the reign she imposed herself on Lord Lumley at Nonsuch where he had a maze, an obelisk and a tableau re-creating one of Ovid’s fables. She greatly appreciated this place and in fact acquired it in 1592. Nevertheless, at the end of the Tudor period the grandest palaces and gardens remained those of Henry VIII.

For more detail, see David Jacques Tudor and Stuart Royal Gardens (Windgather Press, 2024) available through Tudor and Stuart Royal Gardens - Oxbow Books .

For more detail, see David Jacques Tudor and Stuart Royal Gardens (Windgather Press, 2024) available through Tudor and Stuart Royal Gardens - Oxbow Books .

David Jacques OBE is a garden and landscape historian who was Inspector of Parks and Gardens at English Heritage and afterwards a consultant (e.g. at Hampton Court), an author and ran MA courses.

Leave a Reply