Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, was born on 2nd July 1489 in Aslockton, Nottinghamshire, England. He was the son of Thomas Cranmer and his wife Agnes (nee Hatfield). He had an older brother, John, a younger brother, Edmund, and a sister called Alice.

Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, was born on 2nd July 1489 in Aslockton, Nottinghamshire, England. He was the son of Thomas Cranmer and his wife Agnes (nee Hatfield). He had an older brother, John, a younger brother, Edmund, and a sister called Alice.

Cranmer's father died in 1501. His mother sent Cranmer to grammar school and then in 1503, when he was fourteen years old, he was sent to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he studied for a Bachelor of Arts degree. His degree, which comprised logic, philosophy and classical literature, took him eight years to complete and he followed it with a Masters degree, studying the humanists. After obtaining his Masters degree in 1515, Cranmer he was elected to a Fellowship of Jesus College. Following his marriage to his first wife, Joan, he was forced to relinquish his fellowship and became a reader at Buckingham College. Sadly, Joan died in childbirth and the child also died.

After Joan's death, Jesus College reinstated Cranmer as a Fellow and Cranmer began studying theology at the college. In 1520 he went into holy orders and in 1526 he was awarded a Doctorate of Divinity.

From 1527, as a reputable university scholar, Thomas Cranmer was involved in assisting with the proceedings to get Henry VIII's first marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled and it was he who suggested to Edward Foxe and Stephen Gardiner, in 1529, that they should canvass the opinions of university theologians throughout Europe, rather than just relying on a legal case in Rome. The King liked the plan and Cranmer was chosen as a member of the team to gather these opinions. Under Edward Foxe, the team at Rome produced the Collectanea Satis Copiosa ("The Sufficiently Abundant Collections") and The Determinations, which supported, both historically and theologically, the idea that Henry VIII as king exercised supreme jurisdiction within his realm.

In 1532, Thomas Cranmer was appointed as ambassador at the court of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and it was in this role that he saw the effects of the Reformation in cities like Nuremberg. It was while he was at Charles V's court that he met his second wife, Marguerite, after he had become friends with her uncle (by marriage), Andreas Osiander, a Nuremberg reformer. Although Cranmer was a priest, he did not take Marguerite as his mistress, instead, he decided to set aside his vow of celibacy and marry her. Unfortunately, Cranmer was unnable to persuade Charles V to support Henry VIII's annulment from Catherine of Aragon, the emperor's aunt.

In his Bachelor of Arts degree, Cranmer had studied the works of Erasmus and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples. In 1531, Cranmer became friends with Simon Grynaeus, a humanist based in Basel, Switzerland, and it was this friendship which led to Cranmer's later contacts with Continental Reformers from Strasbourg and Switzerland. He became friends with Martin Bucer, a continental reformer, through 18 years of correspondence, finally meeting when Bucer fled to England from Strasbourg in 1549.

In the Autumn of 1532, while in Italy, Thomas Cranmer received a letter dated the 1st October 1532 informing him that he was the new Archbishop of Canterbury, due to the death of William Warham, the former archbishop. Cranmer was ordered home to England to take up his new position, one which had been arranged by Anne Boleyn and her family. Cranmer arrived back in England in January 1533 and was consecrated as Archbishop of Canterbury on the 30th March 1533, after the arrival of papal bulls which were needed for his promotion from priest to Archbishop.

The new archbishop worked closely with his King on the annulment proceedings. Anne Boleyn was already pregnant and the couple had secretly married in January 1533 so the annulment was now considered urgent. On the 10th May 1533, Archbishop Cranmer opened court for the annulment proceedings. Catherine of Aragon did not attend and the king was represented by Stephen Gardiner. On 23rd May, Cranmer ruled that the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon was against the will of God,and the marriage was declared null and void. Five days later, on 28th May, Cranmer declared the marriage between Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn valid and on 1st June he crowned Anne Boleyn Queen of England. In September 1533 he had the pleasure of baptising the couple's daughter, Elizabeth, and becoming her godfather.

It seems that Cranmer was unaware of Anne's fall and the King's interest in Jane Seymour until Anne was arrested on 2nd May 1536. Cranmer wrote to Cromwell in support of Anne but his letter did no good, her fall was a foregone conclusion. On 16th May, Cranmer heard Anne's confession at the Tower of London and on 17th May, he declared that her marriage to the King was null and void. Anne Boleyn was beheaded on 19th May 1536.

In the summer of 1536, Archbishop Cranmer's "Ten Articles" were finally published, after much debate between the conservatives and reformers. These Ten Articles defined the beliefs of the new Church of England, the Henrician Church which had been established after the break with Rome. The first five articles explained that the new church recognised only three sacraments, those of baptism, the eucharist and penance, and the second five articles were concerned with the roles of purgatory, saints, rites and images, and were more conservative in flavour to balance out the reformist first five articles. It was these articles that caused the Northern uprising known as The Pilgrimage of Grace.

The Bishops' Book of 1537, also known as "The Institution of the Christian Man", was written by a team of 46 divines headed by Cranmer to rectify the inadequacies of the earlier "Ten Articles". It set out the religious reforms of Henry VIII and established the new Ecclesia Anglicana, the Church of England.

The Act of the Six Articles of 1539 reversed some of the reforms and reaffirmed traditional Catholic doctrine on transubstantiation, the withholding of the communion cup from the laity, clerical celibacy, the vows of chastity, permission for private masses and the importance of auricular confession. As a result of this act, Cranmer was forced to send his wife and children abroad for safety.

In June 1541, Henry VIII left Cranmer, Thomas Audley and Edward Seymour in charge as a council while he went on a royal progress with his fifth wife, Catherine Howard to the north of England. It was during the king's absence that the council became aware of Catherine's colourful past and possible extramarital affairs. Audley and Seymour chose Cranmer to be the one to tell the King and Cranmer did so by giving the King a letter during mass. Catherine Howard was executed in February 1542.

Cranmer survived a plot by clergymen in 1543 and the king gave him his full support. When Cranmer was arrested in the November, he was supported by the king, and the two of the ringleaders of the plot were sent to prison. Bishop Stephen Gardiner's nephew, Germain Gardiner, who had been heavily involved, was executed.

In 1544, on 27th May, Cranmer's Exhortation and Litany was published, the first officially authorised liturgy in English which is still part of the Book of Common Prayer today.

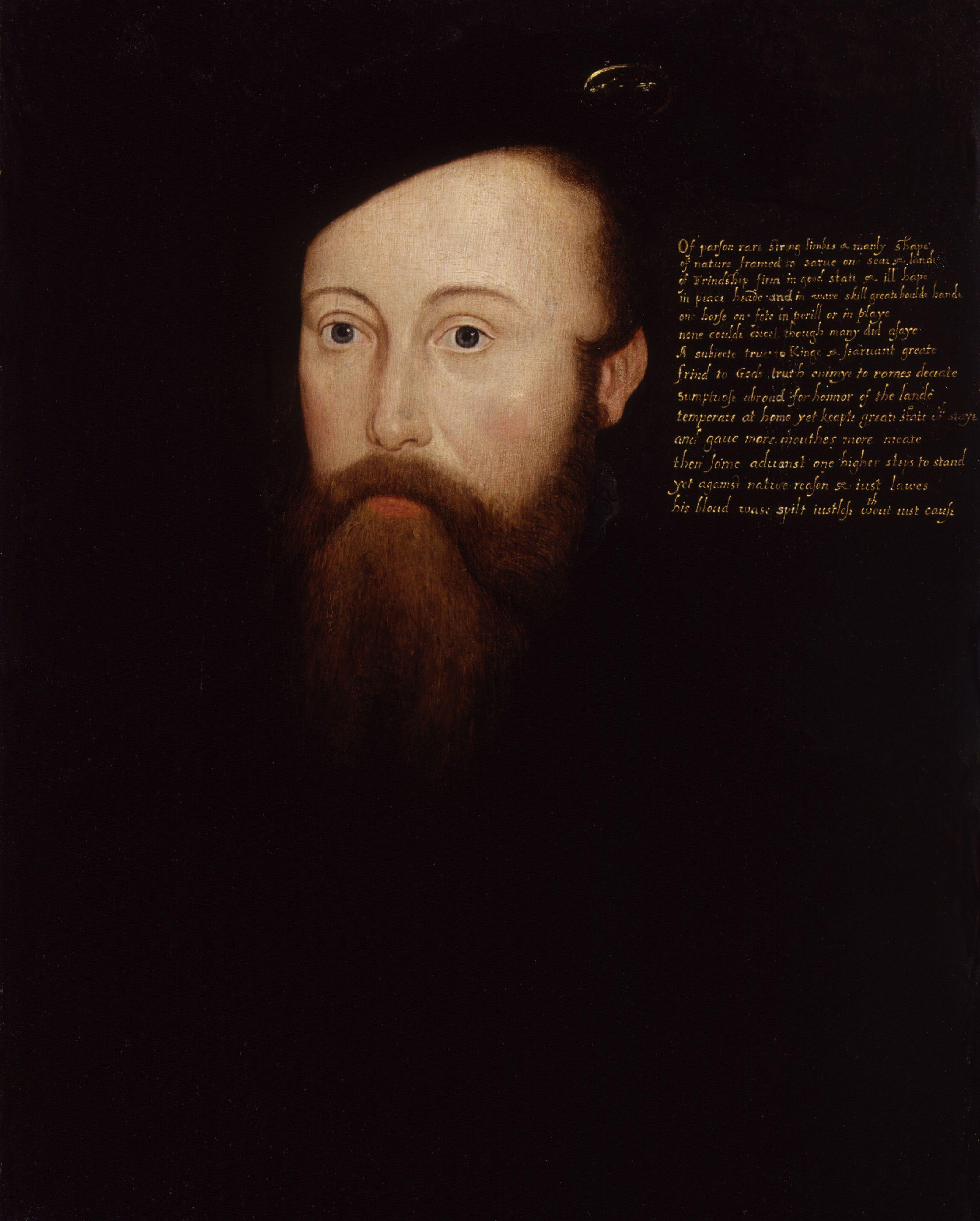

On 28th January 1547, Henry VIII died. While he was dying, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer held his hand and gave the king a reformed statement of faith instead of the usual last rites. Cranmer showed his grief for his master, the king, by growing a beard which was also a symbol of his rejection of the old church and its ideas.

Thomas Cranmer was one of the executors of Henry VIII's will and so was an important part of the Lord Protector's (Edward Seymour's) administration. In August 1547, each parish was instructed to obtain a copy of "The Homilies", a book of twelve homilies, four of which were written by Cranmer. The 1549 Act of Uniformity established "The Book of Common Prayer", which set out the new legal form of worship in England. It was made compulsory in June 1549 which led to the Prayer Book Rebellion, a series of revolts in the south-west of England which then spread into the east of England. The rebels called for the rebuilding of abbeys, the restoration of the Six Articles, the restoration of prayers for souls in purgatory, the policy of only the bread being given to the laity and the use of Latin for the mass. On 21st July, Cranmer preached a sermon at St Paul's Cathedral defending the church line and the Book of Common Prayer.

Although the Prayer Book Rebellion was squashed, it did have a negative effect on the Lord Protector's administration and in October 1549, despite Cranmer supporting Seymour, John Dudley took over Seymour's role. Cranmer was unaffected by this change in government and he continued to work with his friend Martin Bucer on the Ordinal, the liturgy for the ordination of priests, which was published in 1550. Cranmer also went on to publish "The Defence of the True and Catholic Doctrine of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ" in 1550, and in 1552, despite a breach between Cranmer and Dudley caused by the execution of Edward Seymour, Cranmer worked on revising the Prayer Book and canon law and also forming a statement of doctrine. His canon law bill came to nothing but the 1552 Act of Uniformity replaced the Book of Common Prayer with a more Protestant Book of Common Prayer and The Forty-Two Articles were issued on 19th June 1553. However, the Forty-Two Articles were never properly authorised as some bishops opposed them. Cranmer was working on getting bishops to subscribe to them when King Edward VI died and scuppered all of these plans.

On 6th July 1553, Edward VI died, leaving his throne to Lady Jane Grey, who he had appointed as his successor in his "Device for the Succession", which also excluded his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, as heirs to the throne. Thomas Cranmer had opposed the documents but had reluctantly signed them when Edward had asked him to respect his will. Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed queen after Edward's death, but her throne was seized by Mary I in mid July 1553. Although John Dudley and other members of the council were imprisoned, Cranmer was not, and on 8th August 1553 he performed the Protestant funeral rites as Edward VI was buried in the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey. While other reformed clergy fled the country now that the Catholic Mary I was in control, Cranmer chose to stay but, after proclaiming that "all the doctrine and religion, by our said sovereign lord king Edward VI is more pure and according to God's word, than any that hath been used in England these thousand years", he was ordered to stand before the Queen's council on 14th September in the Star Chamber. He was then sent to the Tower of London.

On 13th November 1553, Thomas Cranmer was found guilty of treason and condemned to death. He was then moved to Oxford's Bocardo Prison in March 1554, along Bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, and the three of them were tried in Oxford for heresy on 12th September 1555.

Ridley and Latimer were found guilty immediately and were burnt at the stake on 16th October 1555, but Cranmer had to wait for a final verdict from Rome. On 4th December, Rome took the post of archbishop away from Cranmer and gave permission to the secular authorities to decide Cranmer's sentence.

Between the end of January and mid-February 1556, Cranmer made four recantations, submitting himself to the authority of the monarch and recognising the Pope as the head of the church. On 14th February, his priesthood was taken from him and his execution was set for 7th March because Edmund Bonner was not happy with Cranmer's admissions. Cranmer then made a fifth recantation, fully accepting Catholic theology, repudiating Reformed theology, stating that there was no salvation outside of the Catholic Church and announcing that he was happy to return to the Catholic fold. He participated in the mass and asked for sacramental absolution, which he received.

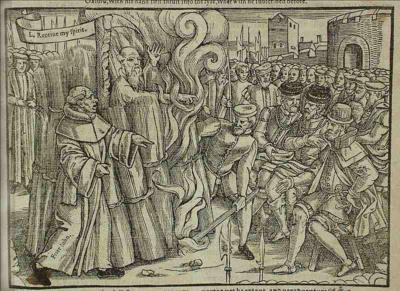

Cranmer's recantation and his return to the Catholic Church should have resulted in him being absolved, but although his execution was postponed, Mary I then announced that it would be going ahead. On 18th March 1556, Cranmer made his final recantation, but his execution date was set for 21st March. On the date of his execution, he was given the opportunity to publicly recant at the University Church, Oxford. Instead of recanting, Cranmer opened with the expected prayer and exhortation to obey the king and queen, but then renounced his recantations, saying that the hand he had used to sign them would be the hand that would be punished by the fire first. Cranmer went on to say: "And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ's enemy, and Antichrist with all his false doctrine." He didn't have the chance to say anymore because he was quickly taken away to suffer his sentence. He was taken to the stake and it is said that he placed his right hand into the flames as they licked around him and as he died he said: "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit... I see the heavens open and Jesus standing at the right hand of God."

Cranmer's execution was unlawful because he was executed even though he had recanted. He had repented and accepted the Catholic faith and even though Bonner had not been satisfied with his first four recantations his fifth seems to have been acceptable. However, Mary would not budge and Cranmer was executed. So why was Cranmer executed when he had quite clearly recanted? Possible reasons include:

- Revenge – Cranmer was the one who had annulled Mary I's parents' marriage and allowed her father to marry Anne Boleyn. Mary and her mother had been treated harshly by Henry VIII after the annulment.

- An example – Was Cranmer used as an example to show how far the Church was willing to go to rid the country of heretics?

- Theology – Did Mary see it as her job to punish and remove the man who could be held responsible for the English Reformation? Did she see herself as doing God's work by getting rid of someone who was doing the Devil's work?

- Politics – Cranmer had been an influential political figure for two decades so perhaps Mary and her council thought that it was dangerous to leave him alive.

An eye-witness recorded the burning of Thomas Cranmer in a letter to a friend, which is transcribed in John Strype's Memorials of the Most Reverend Father in God Thomas Cranmer: Sometime Lord Archbishop of Canterbury...:

"But that I know for our great friendships, and long-continued love, you look even of duty that I should signify to you of the truth of such things as here chanceth among us; I would not at this time have written to you the unfortunate end, and doubtful tragedy, of T. C. late bishop of Canterbury, because I little pleasure take in beholding of such heavy sights. And, when they are once overpassed, I like not to rehearse them again; being but a renewing of my woe, and doubling my grief. For although his former, and wretched end, deserves a greater misery, (if any greater might have chanced than chanced unto him), yet, setting aside his offences to God and his country, and beholding the man without his faults, I think there was none that pitied not his case, and bewailed not his fortune, and feared not his own chance, to see so noble a prelate, so grave a counsellor, of so long continued honor, after so many dignities, in his old years to be deprived of his estate, adjudged to die, and in so painful a death to end his life. I have no delight to increase it. Alas! it is too much of itself, that ever so heavy a case should betide to man, and man to deserve it.

But to come to the matter. On Saturday last, being the 21st of March, was his day appointed to die. And, because the morning was much rainy, the sermon appointed by Mr. Dr. Cole to be made at the stake, was made in St. Mary's church, whither Dr. Cranmer was brought by the mayor and aldermen, and my Lord Williams, with whom came divers gentlemen of the shire, Sir T. A. Bridges, Sir John Browne, and others. Where was prepared, over against the pulpit, a high place for him, that all the people might see him. And, when he had ascended it, he kneeled him down and prayed, weeping tenderly: which moved a great number to tears, that had conceived an assured hope of his conversion and repentance.

Then Mr. Cole began his sermon. The sum whereof was this. First, he declared causes why it was expedient that he should suffer, notwithstanding his reconciliation. The chief are these. One was, for that he had been a great cause of all this alteration in this realm of England. And when the matter of the divorce between King Henry VIII. and Queen Katherine was commenced in the court of Rome, he, having nothing to do with it, set upon it as judge, which was the entry to all the inconveniences that followed. Yet in that he excused him, that he thought he did it not of malice, but by the persuasions and advice of certain learned men. Another was, that he had been the great setter forth of all this heresy received into the Church in this last time, had written in it, had disputed, had continued it, even to the last hour, and that it had never been seen in this realm, (but in the time of schism), that any man continuing so long hath been pardoned; and that it was not to be remitted for ensample's sake. Other causes he alleged, but these were the chief, why it was not thought good to pardon him. Other causes beside, he said, moved the queen and the Council thereto, which were not meet and convenient for every one to understand them.

The second part touched the audience, how they should consider this thing; that they should hereby take example t fear God; and that there was no power against the Lord; having before their eyes a man of so high a degree, sometime one of the chiefest prelates of the Church, an archbishop, the chief of the Council, the second peer in the realm of long time; a man as might be thought, in greates assurance, a king of his side; notwithstanding all his authority and defence, to be debased from an high estate to a low degree; of a counsellor to be a caitiff; and to be set in so wretched estate, that the poorest wretch would not change conditions with him.

The last and end, appertained unto him, whom he comforted and encouraged to take his death well, by many places of Scripture. And with these, and such, bidding him nothing mistrust but he should incontinently receive that the thief did, to whom Christ said, "Hodie mecum eris in paradiso." And out of St. Paul armed him against the terrors of the fire, by this; "Dominus fidelis est; non sinet nos tentari ultra quam ferre potestis;" by the example of the three children, to whom God made the flame seem like a pleasant dew. He added hereunto the rejoicing of St. Andrew in his cross; the patience of St. Laurence on the fire; ascertaining him, that God, if he called on him, and to such as die in His faith, either will abate the fury of the flame, or give him strength to abide it. He glorified God much in his conversion, because it appeared to be only his work; declaring what travail and conference had been used with him to convert him, and all prevailed not, till it pleased God of His mercy to reclaim him, and call him home. In discoursing of which place, he much commended Cranmer, and qualified his former doing.

And I had almost forgotten to tell you, that Mr. Cole promised him, that he should be prayed for in every church in Oxford, and should have mass and dirige sung for him; and spake to all the priests present to say mass for his soul.

When he had ended his sermon, he desired all the people to pray for him, Mr. Cranmer kneeling down with them and praying for himself. I think there was never such a number so earnestly praying together. For they that hated him before, now loved him for his conversion, and hope of continuance. They that loved him before could not suddenly hate him, having hope of his confession again of his fall. So love and hope increased devotion on every side.

I shall not need, for the time of the sermon, to describe his behaviour, his sorrowful countenance, his heavy cheer, his face bedewed with tears; sometime lifting his eyes to heaven in hope, sometimes casting them down to the earth for shame; to be brief, an image of sorrow; the dolor of his heart bursting out at his eyes in plenty of tears; retaining ever a quiet and grave behaviour, which increased the pity in men's hearts, that they unfeignedly loved him, hoping it had been his repentance for his transgression and error. I shall not need, I say, to point it out unto you, you can much better imagine it yourself.

When praying was done, he stood up, and, having leave to speak, said, "Good people, I had intended indeed to desire you to pray for me, which because Mr. Doctor hath desired, and you have done already, I thank you most heartily for it. And now will I pray for myself, as I could best devise for mine own comfort, and say the prayer, word for word, as I have here written it." And he read it standing; and after kneeled down, and said the Lord's Prayer; and all the people on their knees devoutly praying with him. His prayer was thus:-

"O Father of heaven; O Son of God, Redeemer of the world; O Holy Ghost, proceeding from them both, three persons and one God, have mercy upon me most wretched caitiff, and miserable sinner. I, who have offended both heaven and earth, and more grievously than any tongue can express, whither then may I go, or whither should I fly for succour? To heaven I may be ashamed to lift up mine eyes; and in earth I find no refuge. What shall I then do; shall I despair? God forbid. O good God, thou art merciful, and refusest none that come unto thee for succour. To thee therefore do I run. To thee do I humble myself, saying, O Lord God, my sins be great, but yet have mercy upon me for thy great mercy. O God the Son, thou wast not made man, this great mystery was not wrought, for few or small offences. Nor thou didst not give thy Son unto death, O God the Father, for our little and small sins only, but for all the greatest sins of the world; so that the sinner return unto thee with a penitent heart, as I do here at this present. Wherefore have mercy upon me, O Lord, whose property is always to have mercy. For although my sins be great, yet thy mercy is greater. I crave nothing, O Lord, for mine own merits, but for thy name's sake, that it may be glorified thereby; and for thy dear Son Jesus Christ's sake. And now therefore, Our Father which art in heaven, &c."

Then rising, he said, "Every man desireth, good people, at the time of their deaths, to give some good exhortation, that other may remember after their deaths, and be the better thereby. So I beseech God grant me grace, that I may speak something, at this my departing, whereby God may be glorified, and you edified.

First, It is an heavy case to see, that many folks be so much doted upon the love of this false world, and be so careful for it, that or the love of God, or the love of the world to come, they seem to care very little or nothing therefore. This shall by my first exhortation. That you set not overmuch by this false glosing world, but upon God and the world to come; and learn to know what this lesson meaneth which St. John teacheth, "That the love of this world is hatred against God."

The second exhortation is, that, next unto God, you obey your king and queen willingly and gladly, without murmur or grudging; and not for fear of them only, but much more for the fear of God, knowing that they be God's ministers, appointed by God to rule and govern you. And therefore, who resisteth them resisteth God's ordinance.

The third exhortation is, that you love all together like brethren and sistern. For, alas! pity it is to see what contention and hatred one Christian man hath to another, not taking each other as sisters and brothers, but rather as strangers and mortal enemies. But I pray you learn and bear well away this one lesson, to do good to all men as much as in you lieth, and to hurt no man, no more than you would hurt your own natural and loving brother or sister. For this you may be sure of, that whosoever hateth any person, and goeth about maliciously to hinder or hurt him, surely, and without all doubt, God is not with that man, although he think himself never so much in God's favour.

The fourth exhortation shall be to them that have great substance and riches of this world, that they will well consider and weigh those sayings of Scripture. One is of our Saviour Christ himself, who saith, "It is hard for a rich man to enter into heaven;" a sore saying, and yet spoke by Him that knew the truth. The second is of St. John, whose saying is this, "He that hath the substance of this world, and seeth his brother in necessity, and shutteth up his mercy from him, how can he say he loveth God?" Much more might I speak of every part; but time sufficeth not. I do but put you in remembrance of things. Let all them that be rich, ponder well those sentences, for if ever they had any occasion to shew their charity, they have now at this present, the poor people being so many, and victuals so dear. For though I have been long in prison, yet I have heard of the great penury of the poor. Consider that that which is given to the poor is given to God, whom we have not otherwise present corporally with us, but in the poor.

And now, for so much as I am come to the last end of my life, whereupon hangeth all my life past, and my life to come, either to live with my Saviour Christ in heaven, in joy, or else to be in painever with wicked devils in hell; and I see before mine eyes, presently either heaven ready to receive me, or hell ready to swallow me up; I shall therefore declare unto you my very faith, how I believe without colour or dissimulation; for now is no time to dissemble, whatsoever I have written in times past.

First, I believe in God the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, &c., and every article of the Catholic faith, every word and sentence taught by our Saviour Christ, His Apostles, and Prophets, in the Old and New Testament.

And now I come to the great thing that troubleth my conscience more than any other thing that ever I said or did in my life, and that is, the setting abroad of writings contrary to the truth which here now I renounce and refuse, as things written with my hand, contrary to the truth which I thought in my heart, and written for fear of death, and to save my life, if it might be; and that is, all such bills, which I have written or signed with mine own hand since my degradation; wherein I have written many things untrue. And forasmuch as my hand offended in writing contrary to my heart, therefore my hand shall first be punished; for if I may come to the fire, it shall be first burned. And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ's enemy and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine."

And here, being admonished of his recantation and dissembling, he said, "Alas, my lord, I have been a man that all my life loved plainness, and never dissembled till now against the truth; which I am most sorry for." He added hereunto, that, for the sacrament, he believed as he had taught in his book against the bishop of Winchester. And here he was suffered to speak no more.

So that his speech contained chiefly three points, love to God, love to the king, and love to the neighbour. In the which talk he held men very suspense, which all depended upon the conclusion; where he so far deceived all men's expectations, that, at the hearing thereat, they were much amazed; and let him go on awhile, till my Lord Williams bade him play the Christian man and remember himself. To whom he answered, that he did, for now he spake truth.

Then was he carried away, and a great number, that did run to see him go so wickedly to his death, ran after him, exhorting him, while time was, to remember himself. And one Friar John, a godly and well-learned man, all the way traveled with him to reduce him. But it would not be. What they said in particular I cannot tell, but the effect appeared in the end; for at the stake he professed, that he died in all such opinions as he had taught, and oft repented him of his recantation.

Coming to the stake with a cheerful countenance and willing mind, he put off his garments with haste, and stood upright in his shirt; and a bachelor of divinity, named Elye, of Braze-nose College, laboured to convert him to his former recantation, with the two Spanish friars. But when the friars saw his constancy, they said in Latin to one another "Let us go from him; we ought not to be nigh him, for the devil is with him." But the bachelor in divinity was more earnest with him; unto whom he answered, that, as concerning his recantation, he repented it right sore, because he knew it was against the truth, with other words more. Whereupon the Lord Williams cried, "Make short, make short." Then the bishop took certain of his friends by the hand. But the bachelor of divinity refused to take him by the hand, and blamed all the others that so did, and said, he was sorry that ever he came in his company. And yet again he required him to agree to his former recantation. And the bishop answered, (shewing his hand), "This is the hand that wrote it, and therefore shall it suffer first punishment."

Coming to the stake with a cheerful countenance and willing mind, he put off his garments with haste, and stood upright in his shirt; and a bachelor of divinity, named Elye, of Braze-nose College, laboured to convert him to his former recantation, with the two Spanish friars. But when the friars saw his constancy, they said in Latin to one another "Let us go from him; we ought not to be nigh him, for the devil is with him." But the bachelor in divinity was more earnest with him; unto whom he answered, that, as concerning his recantation, he repented it right sore, because he knew it was against the truth, with other words more. Whereupon the Lord Williams cried, "Make short, make short." Then the bishop took certain of his friends by the hand. But the bachelor of divinity refused to take him by the hand, and blamed all the others that so did, and said, he was sorry that ever he came in his company. And yet again he required him to agree to his former recantation. And the bishop answered, (shewing his hand), "This is the hand that wrote it, and therefore shall it suffer first punishment."

Fire being now put to him, he stretched out his right hand, and thrust it into the flame, and held it there a good space before the fire came to any other part of his body; where his hand was seen of every man sensibly burning, crying with a loud voice, "This hand hath offended." As soon as the fire got up, he was very soon dead, never stirring or crying all the while.

His patience in the torment, his courage in dying, if it had been taken either for the glory of God, the wealth of his country, or the testimony of truth, as it was for a pernicious error, and subversion of true religion, I could worthily have commended the example, and matched it with the fame of any father of ancient time; but, seeing that not the death, but cause and quarrel thereof, commendeth the sufferer, I cannot but much dispraise his obstinate stubbornness and sturdiness in dying, and specially in so evil a cause. Surely his death much grieved every man; but not after one sort. Some pitied to see his body so tormented with the fire raging upon the silly carcass, that counted not of the folly. Other, that passed not much of the body, lamented to see him spill his soul, wretchedly, without redemption, to be plagued for ever. His friends sorrowed for love, his enemies for pity; strangers for a common kind of humanity, whereby we are bound one to another. Thus I have enforced myself, for your sake, to discourse this heavy narration, contrary to my mind: and, being more than half-weary, I make a short end, wishing you a quieter life, with less honour, and easier death, with more praise.

The 23rd of March.

Yours, J.A."

Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer are now known as the "Oxford Martyrs". A cross on the ground in Broad Street, Oxford, marks the place where they were burned at the stake and a memorial to them was erected in Oxford in the 19th century. The inscription reads:

"To the Glory of God, and in grateful commemoration of His servants, Thomas Cranmer, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Prelates of the Church of England, who near this spot yielded their bodies to be burned, bearing witness to the sacred truths which they had affirmed and maintained against the errors of the Church of Rome, and rejoicing that to them it was given not only to believe in Christ, but also to suffer for His sake; this monument was erected by public subscription in the year of our Lord God, MDCCCXLI."

You can read more about Thomas Cranmer in the following articles, here and over at The Anne Boleyn Files:

- Thomas Cranmer and Stockholm Syndrome - Beth von Staats' excellent article in the November 2014 magazine.

- Thomas Cranmer’s Everlasting Gift: The Book of Common Prayer

- Edward VI’s Coronation – Primary Source Accounts and Archbishop Cranmer’s Speech

- Thomas Cranmer becomes Archbishop of Canterbury

You can read more about his life in Beth von Staats' book Thomas Cranmer in a Nutshell and Diarmaid MacCulloch's biography Thomas Cranmer: A Life.

Leave a Reply