In the late summer of 1483, two princes, aged twelve and nine, vanished from the Tower of London where they had been imprisoned by their uncle, Richard III. Murder was suspected, but without bodies no one could be certain even that they were dead. Their fate remains one of history’s enduring mysteries, but the solution lies hidden in plain sight in stories we have chosen to forget, of English anti-Semitism, the cult of saints, and in two small, broken and incomplete skeletons.

In the late summer of 1483, two princes, aged twelve and nine, vanished from the Tower of London where they had been imprisoned by their uncle, Richard III. Murder was suspected, but without bodies no one could be certain even that they were dead. Their fate remains one of history’s enduring mysteries, but the solution lies hidden in plain sight in stories we have chosen to forget, of English anti-Semitism, the cult of saints, and in two small, broken and incomplete skeletons.

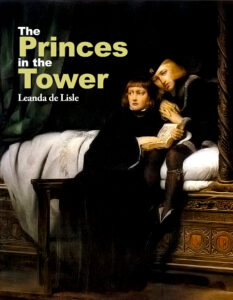

Thus far fiction has provided the best-known answers to what has been turned into a popular ‘whodunit’, with history trailing in fiction’s wake. On the one had we have Shakespeare’s Richard III: a biblical Herod and child killer, whose hunchback is an outward sign of a disfigured soul. This built on a tradition dating back to Richard’s death in 1485, with one Welsh poet describing him then as ‘the sad lipped Saracen’ ‘cruel Herod’ who ‘slew Christ’s Angels’. Later came the reaction with Richard’s enemies accused in his place. The most influential here work is Josephine Tey’s 1951, Daughter of Time, voted by the British based Crime Writers Association the greatest crime novel ever written.

In Tey’s book a detective lying bored in hospital with a broken leg, decides to investigate an historical case with the help of his friends and researchers. Given an image of Richard III, the detective is struck by the contrast between the Richard III of Shakespeare’s play and the gentle, wise face of the portrait. He later learns that Richard was crowned in July 1483, after the young sons of his elder brother, Edward IV, were found to be illegitimate, and without right to the throne. He believes Richard therefore had no motive to kill the princes. So why had he for so long been depicted as their murderer? Tey’s detective is fascinated by how historical myths come into being, and concludes that Richard is a victim of the propaganda of his successful rival, Henry Tudor and his dynsaty, while it is in fact Henry Tudor who had the clearest motive to kill the boys.

So what was Tudor’s motive? After Richard was killed at the battle of Bosworth, Henry Tudor married the sister of the princes, Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth of York, and had Edward’s children declared legitimate. He had no blood right of his own to the throne and needed his wife to be a rightful queen. But if the princes were alive their right was superior to their sister’s. As Tey’s detective notes there is no proof the princes were killed in 1483. They might still have been alive in 1485, and Henry Tudor now had both the motive and the means to kill them and to then cover up his deed. Certainly Tudor made no effort no institute any inquest into the deaths of the princes.

Since Tey’s novel was published an entire industry has grown up with historians and novelists pointing the finger at the Tudor camp. If only Tey’s detective had been given a different portrait than that of Richard III, and if only he had considered the true nature of the myths we still live by, he might have found the genuine solution to the mystery of the boys who disappeared. The portrait I would have chosen to give the detective is of a king who had died a prisoner in the Tower a dozen years before the princes vanished: the frail, childlike, Henry VI.

The last king of the House of Lancaster, Henry VI’s mental illness had triggered the so-called Wars of the Roses, with the rival royal House of York. At the battle of Tewekesbury in 1471, the Yorkist claimant, Edward IV, defeated and killed Henry’s VI’s son. Shortly afterwards Henry VI died in the Tower, ‘of grief and rage’ over the loss of his only child, it was said. But it seems more likely the large dent later found in the back of his skull had something to do with it, and that this wound was inflicted on the orders of Edward IV. Only his half-nephew, Henry Tudor, a Lancastrian through his mother’s illegitimate Beaufort line, was left to represent the Lancastrian cause. He was driven into exile in Brittany, and there he remained in April 1483 when Edward IV died of natural causes, leaving twelve-year old elder son as Edward V.

Child kings rarely made good kings, and by July Edward V had been overthrown by his uncle Richard III, who kept him in the Tower, along with his nine-year old brother, Richard, Duke of York. It was indeed claimed the princes were illegitimate, but not everyone accepted that, and they judged Richard III to be a usurper. To the modern mind, if Richard was, nevertheless a religious man and a good king, he could not now have ordered the deaths of the children, and much has been made of his supposed good character and abilities as a ruler. But in the fifteenth century it was a primary duty of divinely sanctioned kingship to ensure peace, and rule above the fray of tribal divisions. Deposed kings, who posed a threat to national unity, rarely lived long.

What Richard, the good king, underestimated was the enduring loyalty inspired by Edward IV’s memory. In contrast to Henry VI, and other deposed kings, he had been a successful ruler, and his sons had been given no chance to show their mettle. By October 1483 rumours that Richard had killed the princes was fuelling a rebellion. If the boys were still alive, it seems strange Richard did not now say so. But the key question is, if the princes were dead, why had Richard not followed the example of earlier royal killings? In the past the bodies of deposed kings were displayed and claims were made that they had died of natural causes (like grief and rage) so that loyalties could be transferred to the new king.

The fact the princes simply vanished in 1483 is central to the conspiracy theories concerning their fate. So why were the princes disappeared? That the answer lies in the fifteenth century seems obvious, but this is a world almost outside our imagination. Not only was the monastery church Richard III was buried in destroyed during the Reformation period, so was 90% of English religious art, along with libraries and thousands of unique manuscripts (including most of those at Oxford University). And while the Tudors are no longer with us, England remains a country in which the violent rejection of its medieval Catholic past is not merely embedded in English culture, it is enshrined in law. It forms our perspective and creates blind spots.

In 1483 there were images of Henry VI all over the country, painted in churches and illustrating prayer books, because, as Richard III was acutely aware. there had been an unexpected sequel to the king’s murder. Henry VI had been popularly acclaimed a saint with rich and poor alike venerating the mentally ill king as an innocent whose troubled life gave him insight into their own difficulties, and encouraged the hope that he would help them from heaven. Miracles were reported at the site of his modest grave, in Chertsey Abbey, Surrey, and Richard III shared his late brother’s anxieties about the growing power of his cult. It had a strong following even in his home city of York, where a statue of ‘Henry the saint’ had been built on the choir screen at York Minster.

Richard was to take control of the Lancastrian cult in 1484, with an act of reconciliation, moving Henry VI’s body to St George’s chapel, Windsor to be buried alongside Edward IV. But in the meantime there was a high risk that the princes, in whom the religious qualities attached to royalty were combined with the innocence of childhood, would attract a still greater cult. Remember the emotion of the vast crowds outside Buckingham Palace after the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, and imagine it focussed on the tombs of two little princes who could respond to your deepest prayers. The nature of the danger to Richard was obvious, not least when he looked at the history of popular child saints in England.

The parish church of Eye in Suffolk boasts a rare survival: a rood screen dating from around 1480 that depicts Henry VI. Although he died a bearded, middle-aged man, he is painted as a beardless boy: a reflection of his ‘innocence’. Alongside is another image of a popular saint who did actually die as a child: little St William, who like Henry VI was not recognised officially as a saint by the Catholic Church, but was venerated by popular acclaim. A tanner’s apprentice, little William’s mutilated body was found near Norwich in 1144. Local Jews were accused of killing him in a religious ritual: a prototype of the medieval ‘blood libel’ that was to become associated with Jewish persecution in Europe. The local sheriff protected the Jews from immediate retribution, but the boy came to be worshipped as a martyr sacrificed by the incorrigible Jewish unbelievers. Similar cults followed, and even after the Jews were expelled from England in 1290, child murder retained a powerful biblical resonance.

In the fifteenth century the popular Mystery Plays, acted out around the feast of Corpus Christi, included the New Testament story of the Slaughter of the Innocents. This told how King Herod, after hearing of the prophesy of Christ’s reign, ordered the mass slaughter of male infants, hoping to kill Christ. According to the logic of the blood-libel, this was a prelude to Christ’s death on the cross, after which Jews who rejected Christ’s rule had continued to seek to kill Christ’s followers. The Mystery Plays were extremely important in York, where Richard was a member of the Corpus Christi guild. And in the absence of Jews, Richard would have wanted no parallels drawn between himself – the king who had usurped the throne of the dead princes - and Herod.

The vanishing of the princes suited Richard for without a grave there could be no focus for a cult, and without bodies there would be no relics either. Nevertheless, he needed the Edwardian Yorkist opposition to know the princes were dead in order to forestall plots raised in their name. The Tudor historian Polydore Vergil describes how their mother Elizabeth Woodville was given the news, how she tore her hair and screamed with grief. The stories that later emerged describing the killings were horrible. It was said variously that the boys were suffocated with their bedding, drowned, or bled to death. Elizabeth Woodville wanted vengeance and Henry Tudor’s mother, Margaret Beaufort, was the person to suggest how she might get it: a promised marriage between Henry Tudor, and the sister of the princes, Elizabeth of York, would unite the old Lancastrian affinity with Edwardian Yorkists and bring Richard down.

Richard crushed the rebellion that followed in October 1483, and by 1485 Elizabeth Woodville had accepted Richard III as king, as he had hoped she would in 1483. But Henry Tudor had little choice but to fight on, and at the battle of Bosworth in August 1485, he emerged victorious with Richard killed. The princes were revenged, but it soon evident that the new Tudor king, Henry VII, was doing nothing publicly to investigate their fate, or to punish those who had carried out the killings at Richard’s behest.

It is possible Henry feared an investigation would draw attention to some role in the fate of the princes played by a person close to his cause. But contemporaries mention only one name, and it is alongside that of Richard III: Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham. The duke, who came from a Lancastrian family, was a close ally of Richard’s in the overthrow of the twelve-year old Edward V, but turned against Richard after he was crowned. It is possible Buckingham, a ‘sore and hard dealing’ man, encouraged Richard to have the princes murdered, hoping to see Richard killed afterwards and the House of York extinguished. But this does not exculpate Richard, and when he executed Buckingham for his part in the rebellion of October 1483, he never accused him of killing the princes.

So why did Henry Tudor not look publicly for the bodies of his little brothers in law, or hunt out the men who carried out the murders? The answer is that Henry Tudor had his own good reasons for wishing to forestall a cult of the princes. As Tey’s detective noted, Henry’s blood claim to the throne, through his mother’s illegitimate line, was extremely weak. He was determined, nevertheless, not to be seen as a mere king consort to his wife, Elizabeth of York. Henry did not base his right on her legitimacy, but on divine providence – that is God’s direct intervention on earth to make him king.

Henry claimed to be a ‘fair unknown’, a true prince who comes from obscurity to claim his rightful crown as the mythical king Arthur had done. He argued that a few months before the ‘saint’ Henry VI was murdered, the king had prophesised he would rule and that God’s will was confirmed by his victory over Richard at Bosworth. The story is repeated in Shakespeare’s play: as the murder of the princes in Tower takes place, Richard recalls how Henry the ‘saint’ had prophesised Tudor’s reign, and realises that, like Herod, he has missed his mark.

It would not have been wise for Tudor to allow Yorkist royal saints to compete with the memory of Henry VI, whose cult he now encouraged. Nothing was said therefore of the princes after Bosworth, beyond the vague accusation in parliament that Richard III was guilty of ‘murders in shedding of infants blood’. But the memory of Yorkist glory was hard to suppress, and if the princes were dead, they still had relatives: most significantly, the ten-year old Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick, first cousin to the princes and the last of the male line. A Yorkist uprising in 1486, saw Henry place his own little prince in the Tower, with Warwick imprisoned there. It left Henry’s enemies with no effective figurehead to rally round, and so they created them.

In 1487 the Yorkists used a boy – Lambert Simnel - to pose as Warwick. When that failed they found another boy in 1491, Perkin Warbeck, who claimed he was the younger of the princes in the Tower, smuggled abroad after his brother’s murder. It was 1497 before Perkin Warbeck was captured. Henry Tudor kept him alive so that he might publicly confess to his posing as a prince. But in 1499 the Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, demanded further assurance that the Tudor dynasty was secure from any rivals before they would agree to a marriage between their daughter Katherine of Aragon and Henry’s son Arthur Tudor. They wanted Perkin Warbeck dead, but still more they wanted Henry Tudor to kill his royal prisoner, the last in the male line of the House of York.

Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick, had grown up in the Tower, so ignorant of the outside world it was said he did not know the difference between a chicken and a goose. It was easy to trick him into discussing a treasonous plot to escape the Tower with the fake prince Perkin Warbeck, and both were executed that November. Warwick’s death was widely viewed as an act of judicial murder – even the Tudor historian Polydore Vergil recalled the public disgust. During the next reign it was said that Warwick’s death had cursed the Tudor line. No Tudor male born after 1499 ever grew to manhood, and the last Tudor king died aged fifteen with the same skeletal deformity as Richard III (a detail that does not appear in any of Shakespeare’s plays).

But for Henry Tudor the immediate blow came in April 1502, when his first born, Arthur, died shortly after his blood-stained marriage to Katherine of Aragon. It seemed a punishment. Arthur’s death rocked Henry’s claim that he was God’s anointed, and risked prompting the emergence of new pretenders. Perhaps this is why, a month later, a condemned traitor called Sir James Tyrell supposedly confirmed the murder of the princes on Richard’s orders, confessing his own part in the killings, before he was executed.

Henry VIII’s future chancellor, Thomas More, who recorded what he had heard of Tyrell’s confession, wrote that the murdered boys had been buried at the foot of some stairs in the Tower, but that Richard had asked for their bodies to be re-buried somewhere more dignified. Those involved in the reburial had subsequently died, so their final resting place was unknown - a most convenient outcome for Henry Tudor. While the princes’ graves could remain unmarked, like Hamlet’s father, with no ‘hatchment over their bones’, and given no ‘noble rite of burial’ the tomb of Henry VI had come to rival that of Thomas Becket at Canterbury, one of the top three pilgrimage sites in Europe. Thousands still visited it in 1533, the year Henry VIII broke with Rome to marry Anne Boleyn.

But the Reformation had brought to a close the cult of saints in England and the tomb of Henry VI at Windsor had decayed and disappeared entirely by 1611, while our memories of the saints and their power faded. The princes were not forgotten, however, and in 1674, two skeletons were recovered in the Tower, in a place that resembled More’s description of their first burial place. In 1933 they were examined by two doctors; and judged to be two children aged between seven and eleven and between eleven and thirteen. Today the bones of these children are in Westminster Abbey, not far from the tomb of Henry Tudor. DNA testing could establish if they are indeed, close relatives of the skeleton, said to be of Richard III found under that car park in Leicester, and give us the final piece of the puzzle of the vanished princes.

Leanda de Lisle

Leanda de Lisle read History at Somerville College, Oxford University before moving into journalism. She was a writer for Country Life magazine, the Spectator

magazine, and write a bi monthly opinion and editorial column for the Guardian newspaper, amongst other national newspapers.

Her first book “Elizabeth: The Death of Elizabeth & the Coming of King James”, was published in 2005 and was runner up for the Saltire Society’s First Book of the Year award. She also wrote “The Sisters Who Would be Queen; The tragedy of Mary, Katherine & Lady Jane Grey”, and her latest book is “Tudor; The Family Story (1437-1603)”

Leave a Reply