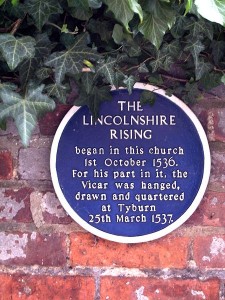

Plaque commemorating the Lincolnshire Rising, opposite south entrance to St James's church, Louth.

On 1st October 1536 Thomas Kendall, Vicar of St. James’ Church, Louth preached a sermon warning the people of his congregation that the Church was in danger. The following day Nicholas Melton and a group of people from the city captured John Heneage, the Bishop of Lincoln’s registrar, as he tried to deliver the assessment of the clergy as ordered by Thomas Cromwell. Melton ripped the papers from Heneage’s hand and burned them. Melton and his followers took Heneage to Legbourne Nunnery where several more of the King’s commissioners were working. They were also captured. On the 3rd it was reported that approximately 3000 men marched to Caistor in an attempt to capture the commissioners working there however the commissioners managed to escape.

From here the towns of Caistor and Horncastle joined the rebellion. On the 4th October Dr John Raynes, Chancellor of the Bishop of Lincoln and Thomas Wulcey, who worked for Thomas Cromwell, were captured and beaten to death by the rebels. On the same day the rebels drew up a list of articles which contained five complaints for the King. These were complaints against the suppression of the monasteries, complaints against various taxes being imposed or rumours of taxes and importantly complaints against those people who were working for the King, including Thomas Cromwell. The rebels felt that these people were from a low birth and were only supporting the dissolution of the monasteries to line their own pockets with the wealth of the churches.

Over the next three days more support came from Towes, Hambleton Hill, and Dunholm as well as from Horncastle and Louth. When the rebels met at Lincoln Cathedral it is reported that they had somewhere between 10 000 and 20 000 men gathered.

Meanwhile on the 8th October in Beverley, Yorkshire a lawyer named Robert Aske became the leader of more men rebelling against the rumours surrounding the dissolution of the monasteries and the revolt happening in Lincolnshire. Then on the 9th October 1536 the rebels of Horncastle, dispatched their petition of grievances to the King. On the 11th the King’s reply to the commoners formally came.

“Concerning choosing of counsellors,” the king wrote, “I never have read, heard nor known, that princes’ counsellors and prelates should be appointed by rude and ignorant common people ; nor that they were persons meet or of ability to discern and choose meet and sufficient counsellors for a prince. How presumptuous then are ye, the rude commons of one shire, and that one of the most brute and beastly of the whole realm and of least experience, to find fault with your prince for the electing of his counsellors and prelates, and to take upon you, contrary to God’s law and man’s law, to rule your prince whom ye are bound to obey and serve with both your lives, lands, and goods, and for no worldly cause to withstand.

As to the suppression of houses and monasteries, they were granted to us by the parliament and not set forth by any counsellor or counsellors upon their mere will and fantasy, as you, full falsely, would persuade our realm to believe. And where ye alledge that the service of God is much thereby diminished, the truth thereof is contrary ; for there are no houses suppressed where God was well served, but where most vice, mischief, and abomination of living was used : and that doth well appear by their confessions, subscribed with their own hands, in the time of our visitations. And yet were suffered a great many of them, more than we by the act needed, to stand ; wherein if they amend not their living, we fear we have more to answer for than for the suppression of all the rest. And as for their hospitality, for the relief of poor people, we wonder ye be not ashamed to affirm, that they have been a great relief to our people, when a great many, or the most part, hath not past 4 or 5 religious persons in them and divers but one, which spent the substance of the goods of their house in nourishing vice and abominable living. Now, what unkindness and unnaturality may we impute to you and all our subjects that be of that mind that had rather such an unthrifty sort of vicious persons should enjoy such possessions, profits and emoluments as grow of the said houses to the maintenance of their unthrifty life than we, your natural prince, sovereign lord and king, who doth and hath spent more in your defences of his own than six times they be worth.”(Ridgway 2011)

Clearly the King was not impressed that the people of his realm would dare stand up in rebellion against him and his government. In response he sent Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk to Lincoln to keep an eye on the rebels. Brandon and his men made their way to Stamford where on the 12th Brandon wrote to the King asking what his orders were. He asked Henry VIII if they should be allowed to pardon the traitors in Lincolnshire or if they should ride forth to suppress the rebels in the north. Brandon worried that if they should pardon the rebels and ride North that if the rebels in Lincolnshire should decide to revolt once more then they would be stuck between two rebelling parties.

Meanwhile the rebellion was now spreading and it was reported that all the people of Yorkshire were now up in arms as well as men coming from East Riding and Marshland to join the rebellion. It was around this time that Robert Ask began to refer to the rebellion as a Pilgrimage seeking the King’s support in preserving the Church and the punishment of those subverting the law.

On the 15th October Henry VIII wrote to Brandon again detailing that he should instruct the rebels to surrender their weapons and give all the information they can about how the rebellion started and if they do so they would be dismissed without any further problems. Henry also demanded that Brandon and the Earl of Shrewsbury who was supporting the Duke, should gather the leaders of the rebellion and question them. The King also stated that he was sending Brandon soldiers on foot and horseback for support. (L&P Vol 11. 717).

From Stamford Brandon and his men moved forward to Lincoln. Meanwhile the rebels marched to Pontefract Castle where Lord Darcy and several other leading men had gathered for safety. However the Castle fell on the 21st and those within, including Lord Darcy joined the rebellion as part of their leadership.

On the same day a herald from Henry VIII was sent to Pontefract Castle to read a proclamation from the King. However, Robert Aske refused to let the proclamation be read. Aske wanted to take the Pilgrimage’s petition straight to the King.

By now the two sides were vastly different in numbers. Brandon and his men only made up approximately 3200 soldiers, the combined forces of Shrewsbury and the Duke of Norfolk only adding a further 6000 while the rebels, according to Sir Brian Hastyngs writing to Shrewsbury were reported to be ‘above 40,000’ (L&P vol. 11 759).

On the 19th October Henry VIII wrote to Brandon advising him that if he could not subdue the rebels by means of conversation…

“then you shall, with your forces run upon them and with all extremity "destroy, burn, and kill man, woman, and child the terrible example of all others, and specially the town of Louth because to this rebellion took his beginning in the same.” (L&P vol. 11 780).

Brandon’s job was clear, he was to stop the rebellion by means of negotiations or if that did not work then he was to make the King’s presence known and to have no mercy upon all those that rose up against the King.

Finally on the 26th October the rebels of the Pilgrimage of Grace paused at Scawsby Leys, near Doncaster where they met the Duke of Norfolk and his army. Despite vastly outnumbering Norfolk and his men Robert Aske decided to negotiate with the Duke. It was agreed upon that two representatives of the Pilgrimage, Sir Robert Bowes and Sir Ralph Ellerker would take the rebels petition to the King. A general truce was proclaimed and Robert Aske ordered the disbanding of the Pilgrimage.

While the King seemed to negotiate with the rebels Brandon was to remain in Lincoln. He and his men were to keep the peace upon the area and to keep an eye out for any further signs of rebellion. He was also charged with seeking out any further stirrers of the rebellion and gaining information from them. Brandon was supplied with military guns and wrote to inform the King that all was quiet and that he had no need of further reinforcements.

In November the Pilgrimage representatives Sir Ralph Ellerker and Sir Robert Bowes met with the Duke of Norfolk and other members of council. After a great deal of discussion the council and the Duke of Norfolk agreed that a general pardon would be given to all the rebels and that their complaints would be taken to a council meeting at York to be discussed. The rebels appeared to be happy with this decision and on the 3rd of December 1536 a general pardon was read to the rebels and they dispersed and went back to their homes.

The King took an unnaturally friendly manner with Robert Aske, talking to him and behaving in a most friendly way to a man who had dared to stand up to the King’s laws. It is thought that Henry decided to take a friendly tone with Aske in the hopes to gain more information from him about who the leaders of the rebellion were. Yet despite all the King’s talk there was no meeting or parliament held to discuss the rebels complaints. This lack of action caused frustration and anger among some of the rebels and in January 1537 a fresh rebellions broke out in East Riding, West Riding, Lancashire, Cumberland and Westmorland. Although these revolts were smaller than that of the previous year the rebels had broken their promise to not riot against the King. This time the King acted swiftly and he commanded that those responsible for the rebellions to be tried and punished. Over the next few over one hundred people involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace and rebellions were tried and sentenced to the traitor’s death of being hung, drawn and quartered.

Rebel leaders such as Robert Aske and Lord Darcy were taken to the Tower of London. Aske was found guilty of his crimes and sentenced to be gun in chains from the battlement at York where he would die a slow, painful death from exposure and starvation.

Sarah Bryson is the author of Mary Boleyn: In a Nutshell. She is a researcher, writer and educator who has a Bachelor of Early Childhood Education with Honours and currently works with children with disabilities. Sarah is passionate about Tudor history and has a deep interest in Mary Boleyn, Anne Boleyn, the reign of Henry VIII and the people of his court. Visiting England in 2009 furthered her passion and when she returned home she started a website, queentohistory.com, and Facebook page about Tudor history. Sarah lives in Australia, enjoys reading, writing, Tudor costume enactment and wishes to return to England one day.

Notes and Sources

Photo from Wikimedia Commons, photographer: Sjwells53.

- Ridgway, Claire (2013), October 1536 – The Pilgrimage of Grace, The Anne Boleyn Files, viewed 18 April 2015, http://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/october-1536-pilgrimage-grace/.

- Ridgway, Claire (2011), 4th October 1536 – The Lincolnshire Rising and Trouble at Horncastle, viewed 18 April, http://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/4th-october-1536-the-lincolnshire-rising-and-trouble-at-horncastle/.

- 'Henry VIII: July 1536, 1-5', in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 11, July-December 1536, ed. James Gairdner (London, 1888), pp. 2-19 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol11/pp2-19 [accessed 15 April 2015].

- Lipscomb, Suzannah (2009), 1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII, Lion Hudson plc, Oxford.

Leaving a man hanging in chains to die of starvation and exposure? And this just months after having his wife killed on false adultery charges? Yes, Henry VIII earned his place in Hell.

The desperation of these men and women must have been deep, for you hear their anger, malice, passion, the defence of their faith and way of life. I don’t condone murder, but they had heard they would face more and more taxes and these men unfortunately got the focus of that wrath, as the King’s representatives. It happened at the start of the peasants revolt, which was the focus of much violence, it would happen in future riots and revolution. Why? Because people resort to attack when they are desperate and nobody will listen to what are often justified grievances.

The royal response was swift. In Lincolnshire it was all over very quickly once the royal army under Suffolk arrived. The local gentlemen made their peace quickly and the ordinary people felt betrayed, but within weeks in Lincolnshire it had collapsed. In Yorkshire it was a different matter for here they had better leaders and were more organised and gained the support of local nobles like Lord Darcy. They were also 30,000 to 50,000 strong as against a force of 8,000 at most sent by a stunned Government, taken by surprise by these risings. Robert Aske, a soldier and legal man for the Earl of Northumberland was their most famous leader and it was he, with two others who faced hanging in chains at the Castle or Clifford Tower, York.

While Robert Aske was no gentleman and made threats against many who didn’t want him there, including the future Queen, Katherine Parr as Lady Latimer and the family of the Earl of Cumberland, including Brandon’s daughter, Lady Eleanor Clifford. His men were rough, but he was honestly defending his beliefs and those of the people who followed him. He was a devout and honest man and the King clearly saw him as someone to negotiate with. Henry’s force were outnumbered and under supplied and it is clear from Norfolk’s letters that there was little choice but to talk and buy time.

Henry’s plan to invite Aske to court for Christmas and issue of a general pardon had the desired effect. It put the rebels off their guard and most went home. The offer of pardon some see as a way of hiding the true intentions of Henry Viii whose own letters make uncomfortable reading, full of terrible threats of retribution if these people, these unnatural people as he saw them had risen against their Prince who had kept them safe from war. The truth was Henry didn’t have the numbers and this was a real danger to his throne, even if they did make an oath not to blame the King, but his evil advisers. After the warm welcome at court, where Aske heard Mass, saw traditional festive customs, was welcomed by the King and Queen Jane, the latter sympathetic to the cause of the rebels or as they called themselves, he was confident of a fair hearing and that the promises of the various meetings would be kept. Those promises included a Parliament to meet and debate the fate of the larger monastic houses and the inheritance of Princess Mary. A pardon was also extended to all. Henry even gave Aske a very rich and wonderful coat to wear.

However, these promises were not kept and, thanks to a second and disastrous rising, which Aske did not support, the King now had the excuse to crush this rebellion once and for all. While in places the executions were horrific and Aske himself was hung in chains, probably taking a slow time to die, although some people believe his chains would have killed him quickly. Monks were hung from their own monastic walls if they had cooperated in the rising, 12_people were killed in Cartmel, four monks and eight lay people, six were hung at Sawley and so on. There is one report that one area saw 70 people killed and no village had someone killed. The numbers are not clear, but from official court records, about 226 people in Yorkshire were executed and 169 in Lincolnshire and Lancashire combined. Norfolk was criticised by Henry for merely hanging people and not drawing or quartering them, the full legal sentence for treason from the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Appalling as this is, from the point of view of the insecure Tudor King, it was justified because they had killed his officials, had attacked those who represented royal authority, had risen up with violence against him as their King and Supreme Head, denied him his titles and authority and had marched on him and his capital. They had received his gracious pardon, in his eyes and broken faith and so they deserved death. Far more could have been executed, but via judicial trials, the main offenders were found guilty and executed. Elizabeth I would find the same way for justice in her eyes by executing 700 after the Northern Rising in 1569 and the numbers executed after the Peasants Revolt are definitely unknown. We know one area alone was recorded as 500 people being executed, many without trial. One village recently did excavation for a new memorial statue and found a cash of almost 300 skulls. Archaeology with bone experts and dating put them to the reign of Richard ii. They had all been removed from the body with swords. Local records showed a number of trials and condemnation from that time, not the numbers found, but this could show that others were killed without trial but then again we only have the documentary as witness anyway. Monarchs saw themselves as next to God and rebellion was a heinous sin and capital crime. During the later period of the British Empire risings, riots and even protest at home, more so in Ireland and India were treason which carried the death penalty, in the seventeen, eighteenth, nineteenth and up to the early decades of the twentieth century. Henry had taken on a lot more power since becoming Supreme Head and he believed his subjects should be obedient in all things. It wasn’t even his idea; it was in Tyndale Obedience of a Christian Man. In addition to this, however, he had become more paranoid and had unpredictable mood swings, possibly going back to inecor more bangs on the head. He was backed into a corner and hit out as a result.