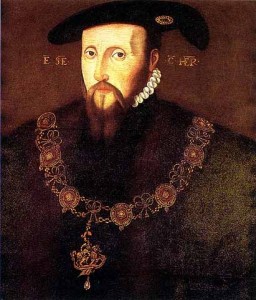

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector of England, was the most powerful man in the country during Edward VI's reign. But how did the king's uncle go from ruling in all but name to losing his head on Tower Hill on this day in 1552?

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector of England, was the most powerful man in the country during Edward VI's reign. But how did the king's uncle go from ruling in all but name to losing his head on Tower Hill on this day in 1552?

His is a story of ambition, betrayal, rebellion, and leadership gone wrong.

Let me tell you more…

Edward Seymour's rise to power was nothing short of meteoric. As a trusted military commander, a staunch Protestant reformer, and, perhaps most importantly, the uncle of the young King Edward VI, he was perfectly positioned to influence the Tudor court. His closeness to Henry VIII in the king’s final years helped him secure his place among England's most powerful men.

When Henry VIII died in January 1547, his will laid out a plan for a shared regency council to govern until Edward VI came of age. It was meant to be a council of equals, with no single man holding absolute power. But Edward Seymour had other ideas. He acted quickly, working with the king’s trusted secretary, Sir William Paget, to consolidate power. In those critical days, Seymour secured the support of key council members, manoeuvered past his rivals, and had himself declared Lord Protector of England and Governor of the King’s Person.

With this role, Seymour wielded immense authority, effectively ruling as king in all but name. While Henry VIII’s will envisioned collective leadership, Seymour's position allowed him to dominate the council and govern almost unilaterally. It was a bold move, but it set the stage for both his triumphs and the tensions that would ultimately lead to his downfall just two years later and ultimately his execution three years after that.

Somerset’s downfall was rooted in his inability to manage relationships within the council. His authoritarian style often alienated those around him. He was known for bypassing the council entirely, relying heavily on royal proclamations to push through his policies, which angered his peers.

William Paget, his trusted ally, tried to warn him in May 1549. In a letter, Paget criticized Somerset’s “choleric fashions” and warned that such behaviour would lead to peril—not only for Somerset personally but for the realm as a whole. Paget wrote, “A king which shall give men occasion of discourage to say their opinions frankly, receiveth thereby great hurt and peril to his realm. But a subject in great authority as your Grace, in using such fashion, is like to fall into great dangers and peril to his own person.”

Somerset ignored Paget’s advice, and his high-handed approach left him increasingly isolated.

1549 was a disastrous year for Somerset. Two major uprisings, Kett’s Rebellion in Norfolk and the Prayer Book Rebellion in the southwest, shook the kingdom. Somerset’s sympathies for the common people—his reluctance to use force and his promises of reform—backfired spectacularly. Riots and chaos spread, and his slow response allowed the rebellions to escalate. When the Crown finally acted, the response was brutal, and over 10,000 people lost their lives. Somerset's indecisiveness during these crises damaged his reputation and highlighted his inability to maintain order.

Somerset’s ambitious foreign policy also contributed to his downfall. The War of the Rough Wooing with Scotland, begun by Henry VIII and continued by Somerset, failed spectacularly. Edward VI’s potential bride, Mary, Queen of Scots, was smuggled to France to marry the French dauphin. And Somerset’s garrisoning strategy in Scotland drained England’s resources and failed to secure a lasting foothold. Meanwhile, tensions with France over Boulogne strained the treasury further, and Somerset’s policies left England vulnerable and financially weakened.

These failures left Somerset vulnerable and it was his inability to maintain alliances within the council and his alienation of previous loyal supporters that sealed his fate. John Dudley, Earl of Warwick (later Duke of Northumberland), emerged as Somerset’s most formidable rival. Warwick, an experienced military leader, capitalised on Somerset’s failures, rallying other disgruntled councillors against him.

In October 1549, Somerset’s position became untenable. Warwick and other councillors openly opposed him. In a desperate move, Somerset issued a proclamation at Hampton Court, calling for troops to defend him and King Edward VI. In the meantime, Warwick was meeting with councillors at his home, Ely Place. There, Warwick blamed Somerset for the recent rebellions and told of how “his own fantasies” had led to the loss of fortifications in Scotland and France. By the time Somerset had moved himself and the young king to Windsor Castle, there were 16 councillors who’d turned against him.

Realising he’d lost, Somerset wrote to the council stating that he’d agree to their terms if the king was not harmed, the peace of the realm was ensured, and they offered reasonable conditions. Edward VI also wrote to the council warning them to treat his uncle gently.

On 10th October, Somerset was informed that he was being deprived of his protectorship and that 29 accusations had been drawn up against him. He was ordered from the king's presence and on 11th October 1549, following his surrender, Somerset was arrested and brought in front of his nephew, the king, who summarised his charges as “ambition, vainglory, entering into rash wars in mine youth, negligent looking on Newhaven, enriching himself of my treasure, following his own opinion, and doing all by his own authority.”

On 13th October, Somerset’s protectorate was dissolved and the next day, he was taken to the Tower of London. He confessed to the charges laid against him and on 14th January 1550 he was officially deprived of the protectorate by act of Parliament.

Remarkably, Somerset made a brief return to favour in 1550. He was released from the Tower, pardoned, and restored to the privy council and the privy chamber. However, his return was short-lived. In 1551, he was accused of plotting to kill Warwick, now the Duke of Northumberland, the Marquess of Northampton and others at a banquet, and also plotting to secure the Tower of London and “raise London”.

Somerset was arrested again and on 1st December 1551, he was tried for high treason by a jury of his peers. He was acquitted of treason, but found guilty of felony for bringing men together to riot. Felony was still a capital crime, so he was condemned to death by hanging. His sentence was commuted to beheading and on this day in Tudor history, 22nd January 1552, he was taken to the scaffold at Tower Hill.

Chronicler and Windsor Herald Charles Wriothesley recorded:

“Fryday, the 22 of January 1552, Edward Seimer, Duke of Somersett, was beheaded at Tower Hill, afore ix of the clocke in the forenone, which tooke his death very patiently, but there was such a feare and disturbance amonge the people sodainely before he suffred, that some tombled downe the ditch, and some ranne toward the houses thereby and fell, that it was marveile to see and hear; but howe the cause was, God knoweth.”

It is not known what that disturbance was, whether it was thunder or an explosion, but then Sir Anthony Browne rode towards the scaffold, causing a rumour to go around the crowd that Somerset would be pardoned. He wasn’t. Somerset died with dignity and courage, and it fortunately took just one stroke of the axe to kill him.

In his diary, King Edward VI simply wrote, “The Duke of Somerset had his head cut off upon Tower Hill between eight and nine o’clock in the morning.”

His execution marked the tragic end of a man who had once held the highest position in the realm.

Somerset had climbed to dizzying heights, he’d been king in all but name, but he’d been a failure as a leader. He’d gone his own way, refused to listen to others, and had been reluctant to act against rebellions, finding it hard to be harsh to people whose grievances he sympathised with. We only have to compare his dithering in the 1549 rebellions with how Henry VIII handled the Pilgrimage of Grace rebellion in 1536. Somerset in 1549 – dither, dither, dither, no, I don’t want to send Crown troops against our own people, no, dither, dither, oh perhaps I should. Henry VIII in 1536 “destroy, burn, and kill man, woman, and child the terrible example of all others” and “take the said abbot and monks forth with violence and have them hanged without delay in their monks’ apparel”.

Wow! I don’t like what Henry VIII did, but that’s what the people and the council expected from a leader.

Somerset was a gifted military commander and a man with experience in administration, but he was no ruler.

Leave a Reply