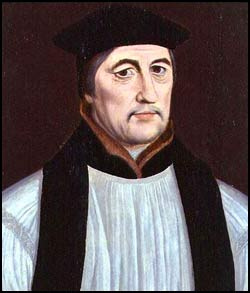

Stephen Gardiner’s date of birth is not known, with some saying 1483 and others saying 1493 or 1497, but he was born in Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk. His father was William Gardiner (some say John Gardiner), a cloth merchant and a mercenary hired during the War of the Roses. According to Welsh accounts of the 1485 Battle of Bosworth, it was “Wyllyam Gardynyr” who killed King Richard III with a poleaxe. Sir William Gardiner later married Helen Tudor, a woman said to have been the illegitimate daughter of Jasper Tudor, uncle of King Henry VII.

Stephen Gardiner’s date of birth is not known, with some saying 1483 and others saying 1493 or 1497, but he was born in Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk. His father was William Gardiner (some say John Gardiner), a cloth merchant and a mercenary hired during the War of the Roses. According to Welsh accounts of the 1485 Battle of Bosworth, it was “Wyllyam Gardynyr” who killed King Richard III with a poleaxe. Sir William Gardiner later married Helen Tudor, a woman said to have been the illegitimate daughter of Jasper Tudor, uncle of King Henry VII.

As a young man, Gardiner met the famous humanist scholar, Desiderius Erasmus, in Paris and he studied at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. He received the degree of Doctor of Civil Law in 1520 and of Canon Law in 1521, and went on to work for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey as secretary. He met Henry VIII for the first time in 1525 at The More in Hertfordshire for the signing of the Treaty of the More between the King and Francis I of France. Two years later, in 1527, Gardiner and Sir Thomas More worked as commissioners in arranging, with the French ambassadors, a treaty to obtain support for an army against the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, in Italy.

In 1527, Gardiner accompanied his master, Wolsey, on a diplomatic mission to France to gain the French King’s support for “the King’s Great Matter” (or “secret matter”), his wish to divorce Catherine of Aragon. A year later, Gardiner was sent to Italy with Edward Foxe, the provost of King’s College, Cambridge, to secure a decretal commission from the Pope which would allow Cardinal Wolsey to rule on the validity of the King’s marriage without appeal to Rome. Although Gardiner was an expert on canon law, and so was at a great advantage, Pope Clement VII had recently been imprisoned by Charles V’s troops, and was wary of offending the Emperor who was Catherine of Aragon’s nephew, and so refused to grant the decretal commission and instead granted a general commission to allow Cardinal Wolsey to try the case in England with the Papal Legate, Cardinal Campeggio. You can read more about the Legatine Court in Cardinal Campeggio and the Legatine Court.

In 1526, Gardiner was appointed Archdeacon of Taunton and then in 1529 Archdeacon of Norfolk, a post from which he resigned from in 1531 when he became Archdeacon of Leicester. In November 1531, he was appointed Bishop of Winchester after successfully procuring a decision from the University of Cambridge on the unlawfulness of a man marrying his dead brother’s wife. However, he offended the King a year later when he was involved in preparing the “Answer of the Ordinaries”, a reply to the “Supplication Against the Ordinaries”.

In May 1533, Gardiner assisted the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, in pronouncing the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon null and void, and in 1535 he was one of the bishops asked to vindicate Henry VIII’s new title “Supreme Head of the Church of England”, something which he did by writing his treatise De vera obedientia, in which he argued that rulers were entitled to supremacy in their own country’s churches, and that the pope had no legitimate power over other churches.

Between 1535 and 1539, Gardiner was mostly abroad on diplomatic missions, but in 1539 he helped to prepare “The Six Articles”, which reaffirmed the traditional Catholic doctrine on transubstantiation, clerical celibacy, the vow of chastity, the withholding of the cup from the laity at communion, private masses and auricular confession. In 1543, Gardiner was involved in the Prebendaries’ Plot against Cranmer, along with his nephew, Germain Gardiner. The plot failed when the King supported Cranmer, but Gardiner survived, although his nephew, the scapegoat, was executed for treason. In 1546, Gardiner, along with Lord Chancellor Wriothesley, attempted to turn the King against his sixth wife, the Reformist Catherine Parr. The plot failed when Catherine managed to reconcile with the King.

Philip of Spain and Mary I

It is not clear what Gardiner’s role was in the Marian persecutions, but it appears that he preferred to try and persuade people to save themselves by recanting and reconciling themselves to the church. It has been pointed out that in his own diocese, nobody was persecuted until after Gardiner’s death.

In May 1555, Gardiner carried out his last diplomatic mission to France, to promote peace, a mission that was not successful, and in October 1555 he opened Parliament. On the 12th November 1555, after being taken ill at the end of October, the famous Tudor statesman and lawyer, Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester and Lord Chancellor of England, died. It is thought that he was in his sixties, and that he had been suffering from jaundice and dropsy. It is said that as he lay dying, the story of the Passion was read to him, and that his dying words, after hearing of the denial of Peter, were “Erravi cum Petro, sed non flevi cum Petro”, “Like Peter I have erred, unlike Peter I have not wept”, an allusion to his weakness during the reign of Henry VIII. He was laid to rest at Winchester Cathedral in what is now known as the Bishop Gardiner Chantry Chapel.

Bishop Gardiner's Chantry Chapel

(Text taken from Claire's On This Day in Tudor History)

While Stephen Gardiner would not be first on a list of my favourite Tudors, most people don’t realise how much of a brilliant man and how much he was an integral part of the religious and political developments at the Tudor Court. He is often maligned because of his involvement in a plot to bring down Katherine Parr, but to be honest, he was taking his cue from Henry moaning about her practically preaching to him every night. It isn’t clear what changed, but Gardiner was on good terms with Henry’s sixth Queen at first and married them. Katherine became a radical Protestant and he was duty bound to enforce the law, although he was a traditional Catholic and would naturally take action against heresy. His own religious views seem to have been flexible as he accepted the King’s supremacy. His nephew, however, still denied the supremacy and became a martyr because of it. Henry was informed that Gardiner harboured secret reservations about the new monarchy and new ideas and he ordered his arrest for treason. However, Gardiner was lucky enough to find out and made his way to Henry, confessed that he once did believe like that but he now had seen the light and Henry pardoned him. His devotion to the King’s will was complete after that and he was certainly devoted to prosecuting the heresy growing up around the Court, the Queen and in London. He was involved in the movement against Anne Askew and the Queen, which resulted in the martyrdom of one and near miss for later. Gardiner fell out of favour soon afterwards.

He was actually, as you say moderate but he did have to do his job. He didn’t use torture, he preferred persuasion, although Anne Askew was tortured, but not on his orders. Anne Askew was illegally tortured by the Earl of Southampton and Chancellor Audley themselves and to a very cruel extent. It was terrible as was the cruel fate which she and many others faced during the Tudor period.

Stephen Gardiner stood by his principles, being imprisoned himself under Edward and then defending the traditional Catholic Church under Mary. His role in the King’s Great Matter as a young man is often overlooked and his learning and letters reveal a complex and brilliant man, often portrayed as insensitive and as a campaigner. There was far more to him than that.

We now know that William Gardiner didn’t kill Richard iii and evidence shows it was actually Rhys ap Thomas, a Welshman with a halibard, war hammer. That was one of two fatal blows. He suffered ten in all. It makes sense that he was killed by a Welshman as he was in the middle of Henry’s Welsh pikemen, fighting on foot and between the French/Breton vanguard and the traitors galloping into his flanks under Sir William Stanley. The poems of Guytor Glynn confirmed this account. Jean Molinet believed the man responsible was William Gardiner but that account has been disproved by Susan Fenn in her new biography about Rhys ap Thomas. One thing we do know for certain, the man was Welsh and he used a pollaxe or halibard for the fatal blow.