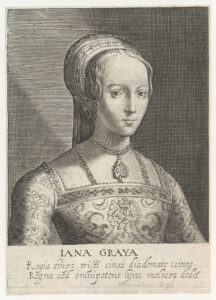

The van de Passe Engraved Portrait. It was engraved by Willem and Magdalene van de Passe and first published in 1620. It was probably based on the Hastings Portrait. It actually depicts Katherine Parr.

Among portraits of the many kings and queens of England and Great Britain, those of the Tudor monarchs are arguably some of the most readily recognized. Henry VIII’s portrait by Holbein, with its confident visage, assertive hands-on-hips pose, and bold stance, is essentially iconic for the Tudor period as a whole, for example. Yet one Tudor monarch remains entirely absent from the pictorial record: Jane Grey Dudley, the ‘Nine-Days Queen’ of 1553. No reliably authentic portrait of Queen Jane has yet been identified, despite dozens of portraits from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries having been put forward over the past four and half centuries. Most recently, the acquisition in 2006 by the National Portrait Gallery of the so-called Streatham Portrait was heralded by significant international publicity. That portrait ultimately proved to date to at least four decades after Jane’s death, however, and the authenticity of the likeness remains dubious. Similarly, the Wrest Park Portrait exhibited in 2007 by Philip Mould Gallery as a posthumous historical portrait of Jane

has since been shown to be an early life portrait of Mary Neville Fiennes, Lady Dacre.[1] And the presentation in the same Mould exhibition of the Yale Miniature as a life portrait of Queen Jane has failed to garner support from any other authority. Each new announcement has been greeted by a flurry of media attention, but each painting has subsequently slipped quietly into the background upon more careful investigation. Even my own early study of the Fitzwilliam Portrait in 2005 suffered the same ignominious fate, and rightly so.[2]

The question therefore arises as to why no portrait of Queen Jane seems to have survived. She remains, after all, one of the most popular female figures from sixteenth-century Britain, after Elizabeth I, Anne Boleyn, and Mary Stuart. She was celebrated across Europe during her own lifetime as a superior intellect and popularized immediately following her execution in 1554 for the admirable way in which she met death. Her younger sisters gained widespread support as successors to the childless Elizabeth I, until Katherine Grey’s death in 1568 and Mary Grey’s death in 1578, keeping Jane indirectly in the public eye throughout that period. At least one modern historian has cited an “intense obsession” with Jane among the British early in the eighteenth century.[3] And Jane became something of a darling among writers in the nineteenth century owing to a perception that she personified Victorian feminine ideals. So if multiple authentic portraits of Jane’s sister Katherine have survived, and at least one probably-authentic portrait of her sister Mary, why have no authentic portraits of Jane herself survived? The answer lies in the complex intersection of the relative ages of the sisters at their respective deaths, the disposition of the Grey family estate, the politics of the era, and the vicissitudes of portrait collecting across more than four centuries.

The Northwick Portrait. By an unknown artist. In 1590, it was in the collection of John Lumley, Baron Lumley. It is now in a private collection in the UK. Only since 1965 has it been said to depict Jane Grey. It actually depicts Katherine Parr.

It has never before been published in full color, and was virtually unseen since 1965. Took me over a year to track it down and then to convince the owner to let me see it.

Most students of Tudor history are aware that Jane Grey Dudley died at barely seventeen years of age. As a result, there was little opportunity for production of a painted likeness. Portraiture of living persons was still a relatively new cultural phenomenon in England in the sixteenth century, though its popularity there was expanding very rapidly. But they were not often commissioned for sentimental reasons or in any effort to create a remembrance of a beloved relative. Paintings of quality usually cost significant sums of money and thus were largely limited instead to expressions of individual status within some larger social structure beyond the family. Portraits of men of the sixteenth century can often be shown to coincide with elevation to a new political office or title of nobility or to mark participation in some significant public event, such as a military battle. Women’s portraits can similarly often be associated with their marriage or their safe delivery of a male heir into the family. Women and children were seldom recognized as having individual status but were instead subsumed under that of their family. As an illustration of this, we might consider the scarcity of portraits of children from Tudor England. Very few portraits of individual children are known to have been produced, and few such portraits have survived. The exceptions are almost always minor children of the reigning monarch, such as Holbein’s portrait of the future Edward VI as an infant or William Scrot’s portrait of Princess Elizabeth from the 1540s. Since Jane was not the child of any reigning monarch, nor even the grandchild of one, we cannot today expect that any portrait of her would have been produced prior to her reaching the age of eligibility for marriage. For Jane, this did not occur until the winter or spring of 1552-1553, when she reached the age of sixteen.[4] And while Jane may have been viewed at that time by her family and its allies as a potential bride for Edward VI, the king was instead negotiating for a match with Elizabeth of France. Jane did not become a serious candidate for marriage until May of 1553, when John Dudley began promoting her as a successor to the dying Edward. Further, it took some time for an artist to be selected, one or more sittings to occur, and the actual paint-work to be completed. The span between Jane’s marriage in May and her imprisonment in mid July was a very brief one crowded with other concerns that may well have left insufficient time to plan and to create a portrait of her. And it is perhaps noteworthy that every authentic portrait of Jane’s sisters Katherine and Mary actually post-date their own respective marriages by two or more years.[5] There was precious little opportunity for any portrait of Jane to have been produced prior to July 1553, and probably no opportunity whatsoever thereafter.

Yet we have reliable documentation that at least one portrait of Queen Jane was produced before 1559, and it is altogether probable that that portrait was an authentic likeness, even if it was not taken from a life sitting. The portrait was owned by Elizabeth Cavendish, known to history as Bess of Hardwick, a close friend of the Grey family. Bess had served as a lady in waiting to Jane’s mother Frances during the 1540s and had wed her second husband in the Grey family chapel at Bradgate in 1547. Jane herself even stood godmother to Bess’s daughter Temperance in 1549. An inventory of Bess’s possessions taken in relation to her third marriage to William St Loe in 1559 revealed that Bess displayed a portrait of Queen Jane in the very private space of her personal bedchamber. [6] It seems exceedingly unlikely that Bess would have held a portrait of Jane so closely were it not an authentic likeness. Sadly, that portrait largely disappeared from the historical record after 1560, and its current whereabouts are entirely unknown. Recent research suggests that it became severely damaged and may have been deliberately destroyed early in the nineteenth century.

Any portrait of Jane owned by the Grey family itself may likewise have become severely damaged and been destroyed. Jane’s father Henry Grey was attainted of treason early in 1554 and his estates, including the family seat of Bradgate in Leicestershire and their London residence of Sheen Priory, were seized by the Crown. Sheen was restored as a Carthusian monastery under Mary I, and it is rather doubtful that the monks would have preserved any portrait of Protestant Jane. Bradgate was eventually returned to Jane’s uncle, John Grey, but he and his heirs preferred Pirgo Palace in Essex and Enville Hall in Staffordshire. Bradgate was little used and poorly maintained, eventually falling to ruin by the beginning of the eighteenth century. And while Jane’s mother Frances did recover some few minor estates after 1554, she left virtually all of her property to her second husband Adrian Stokes, who sold everything off to pay his own enormous debts.[7] Jane’s sisters Katherine and Mary Grey are not documented as having inherited or having possessed any portraits of Jane. Thus by the time of Mary Grey’s death in 1578, no close adult member of the immediate Grey family remained alive with an active interest in preserving a portrait of Jane Grey Dudley.[8]

The Klabin Portrait. Virtually unknown to any art historian prior to my uncovering it in 2014 in a small private museum in Rio de Janeiro, and it has never before been published. It is inscribed “Iane Grey/ An[n]o Dom[ini] 1553/ Aetatis 16”, but the inscription was added long after the painting was created. It is French, late 16th century, and depicts an unknown French woman.

As noted, the only two portraits of Jane documented in the sixteenth century, those owned by Bess of Hardwick and John Lumley, both disappeared at some point over the past four and half centuries. Each illustrates one of the two principal reasons why identifiable authentic portraits of Jane have failed to survive. In the instance of the Chatsworth Portrait owned by Bess of Hardwick in 1559, the evidence suggests that the portrait suffered significant decay over time, either through conscious neglect or natural processes. Most habitable rooms in pre-modern houses included a fireplace, and those fireplaces often discharged some measure of smoke into the room itself. As is the case with modern households in which the residents smoke tobacco products, smoke residue could and did accumulate over time, eventually obscuring the image. Inventories taken in the nineteenth century at the houses of Bess’s descendants, Chatsworth House and Hardwick Hall, revealed over two dozen portraits in which the image was entirely obscured by soot and dirt.[10] That soot and dirt also often caused chemical reactions in the protective varnish, the paintwork itself, or even the supporting wood panel, especially in those instances when the panel became wet for some reason, e.g.: ‘rising damp,’ flooding, leaking roofs. Panels became warped, split, or riddled with wood worm. Rather than attempt to repair the damage, owners too frequently simply disposed of the paintings in order to make way for new acquisitions that more nearly accorded with current aesthetics. In more extreme instances, paintings were lost through failure to maintain the houses in which they were held (e.g.: Bradgate) or through destruction of the entire house as a result of fire or war. Innumerable paintings from the sixteenth century are known to have been lost through these forms of neglect and accident.

The Soule Portrait. Another one that had not been examined by any art historian since the 1950s and that took me several months to track down. This painting is unusual in that the sitter was entirely unidentified until 1954, when she became known as Elizabeth I When Princess. It has recently been firmly dated to 1560-65. I believe it to depict Katherine Grey Seymour, younger sister of Jane Grey.

Even among those sixteenth-century portraits that survive today, many of the sitters cannot be identified for a variety of reasons. It was relatively uncommon for portraits to be labeled with the sitter’s name, for example. Over time, as a portrait passed from one generation to the next, there were fewer and fewer people remaining alive to attest to the identity of the person depicted, as was the case with the Wrest Park Portrait. By 1675, that 125-year-old portrait had entirely lost its identity even though it was still in the possession of the sitter’s direct lineal descendants. The situation is directly comparable to finding today a box of 75- or 100-year-old unlabeled family photographs in an attic. Though those photographs depict your own ancestors, how do you go about identifying them if there is no one left alive to offer adequate clues? Since none of Jane’s immediate family members were left alive after 1578, it is perhaps understandable that any surviving authentic portrait of her might have lost its identity. Even when portraits were labeled, those labels were usually added many years or even decades after the fact and were not always correct. John Lumley famously added painted labels to the surfaces of many of the portraits in his collection, and while most of the surviving labels do seem to have been accurate, others became decayed and are thus no longer legible. Such is the case with the Northwick Portrait, which originated in the Lumley collection and was sometimes said to depict Jane Grey. The Lumley label or cartellino had become entirely illegible by the end of the eighteenth century, so that we cannot today rely on it for identifying the sitter depicted. The labels were ordinarily added atop the layers of protective varnish, and as the organic compounds in the varnish deteriorated, the uppermost layers sloughed off, taking the painted label with it. That process is best illustrated by the Soule Portrait. Photographs taken of it in 1937 and again in 1954 reveal the presence of an inscription added atop the varnish sometime after 1602. Today, just sixty years since the last photograph, the inscription is entirely gone, carried away by flaking varnish. Thus even when a portrait has survived the ravages of time and neglect, it was rare that later owners could still correctly identify non-labeled portraits, rarer still that portraits actually bore an accurate label, and even more rare that such labels themselves survived.

Instead, we rely today on surviving written documentation combined with provenance, or ownership history, of the painting to aid in attempting to identify otherwise unidentified sitters in sixteenth-century portraits. Household inventories and wills are both valuable tools in this process. When widows re-married, or when a householder died, inventories of the household goods were very often taken to meet various legal requirements. Sometimes those inventories are exceedingly detailed and describe individual paintings by size, content, and even artist attribution, as is the case with the Lumley Inventories. At other times, they are frustratingly vague and focus only on collective financial values. Many of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century inventories of Chatsworth House and Hardwick Hall, for example, reveal only the total number of paintings in a given room of the house and their total appraised value, with no mention whatsoever regarding subject content or physical size. Alternatively, owners sometimes named and described individual heirloom portraits in their wills when bequeathing them to specific heirs. Such was the case with the Syon Portrait, which can be traced through a series of wills from its original owner early in the seventeenth century down to 1748, and from there through household inventories to the present. But such convenient conjunctions of wills, inventories, and provenances that allow tracking a painting across four centuries are extremely rare. In the vast majority of cases, the best we have is a provenance for the past century only, or a single mention in an ancient will, or a vague description in s single inventory from the very distant past. Absent the complete documentary trail or any reliable name inscription applied to the painting by the original artist, portraits commonly became misidentified, leaving the sitter without a name today.

Owing therefore to the apparent loss of the Chatsworth Portrait through damage and destruction, to the decay of the label on the Lumley Portrait, to the lack of any long-surviving immediate family members with an interest in preserving the Grey domestic estates and the objects they held, to the Elizabethan perception that Jane was an enemy of the Crown, and to the absence of an adequate written record to aid in locating lost or misidentified portraits, it seems unlikely that any portrait of Jane painted from the life has survived and can be identified today. The greatest prospect for ‘seeing’ Queen Jane may instead lie in identifying some posthumous portrait with sufficient direct connections to Jane and her family to allow judging it a reasonably authentic likeness.

J. Stephan Edwards, PhD

- J. Stephan Edwards, “Framing a Life in Portraits: A ‘New’ Portrait of Mary Nevill Fiennes, Lady Dacre,” British Art Journal XIV:2 (Autumn 2013), 14–20. ↑

- J. Stephan Edwards, “A New Face for the Lady,” History Today 55:12 (December 2005): 44–45. ↑

- Jean I. Marsden, Fatal Desire: Women, Sexuality, and the English Stage, 1660-1720 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006), 171. ↑

- J. Stephan Edwards, “On the Birth Date of Lady Jane Grey,” Notes and Queries 54:3 (Sept. 2007), 240-242; “A Further Note on the Date of Birth of Lady Jane Grey,” Notes and Queries 55:2 (June 2008), 146-148. ↑

- The best known portrait of Katherine Grey, a miniature now at Belvoir Castle, dates to no earlier than the winter of 1562-1563, two years after her marriage to Edward Seymour and one year after the birth of her first son. A second miniature now in the Victoria and Albert Museum is inscribed ‘wife of the Earl of Hertford,’ indicating that it too probably post-dates her marriage. The single known portrait of Mary Grey is inscribed ‘1571,’ six years after her marriage to Thomas Keyes. ↑

- Chatsworth Devonshire MSS, Hardwick Hall Drawers H/143/6, f.3v; Gillian White, ‘That whyche ys nedefoulle and nesesary’: The Nature and Purpose of the Original Furnishings and Decoration of Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire (Ph.D. diss., University of Warwick, 2005), II: 389-415. ↑

- National Archives, PROB 11/42B, Will of Lady Frances, Duchess of Suffolk, dated 9 November 1559. ↑

- Jane Grey had no surviving issue. Her father died in 1554, her mother in 1558. Her sister Katherine Grey Seymour’s eldest son Edward was not yet seven years old when his mother died in 1568. Edward survived until 1612 but is not known to have possessed any portrait of his aunt. Jane’s youngest sister Mary Grey Keyes died without issue in 1578. ↑

- Lionel Cust, “The Lumley Inventories,” The Sixth Volume of the Walpole Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1918), 25; Catharine MacLeod, Tarnya Cooper, and Margaret Zoller, “A List of Portraits in the Lumley Inventory,” in The Lumley Inventory: Art Collecting and Lineage in the Elizabethan Age, edited by Mark Evans (London: The Roxburghe Club, 2010), Appendix Three. ↑

- Devonshire MSS CH36/7/1A; CH36/7/2, 90-91 and 137-140. ↑

Leave a Reply