Penelope Devereux, also known as Penelope Rich and Penelope Blount, was the elder daughter of Walter Devereux and his wife, Lettice Knollys. Penelope was from a distinguished family, with her maternal grandmother being Lady Mary Boleyn, sister of Queen Anne Boleyn, and both her mother and father serving Queen Elizabeth I. Penelope's father was rewarded for his loyal service to Elizabeth, fighting in Ireland, with the earldom of Essex, and he was a notoriously chivalric figure during Elizabeth's early reign and the ideal model of manhood. After her father's death, Penelope's mother went on to marry Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the queen's favourite, in secret, causing Elizabeth to nickname Lettice "the she-wolf". Penelope became the ward of Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, after her father's death in 1576 and was educated in his household in Leicestershire.

Penelope Devereux, also known as Penelope Rich and Penelope Blount, was the elder daughter of Walter Devereux and his wife, Lettice Knollys. Penelope was from a distinguished family, with her maternal grandmother being Lady Mary Boleyn, sister of Queen Anne Boleyn, and both her mother and father serving Queen Elizabeth I. Penelope's father was rewarded for his loyal service to Elizabeth, fighting in Ireland, with the earldom of Essex, and he was a notoriously chivalric figure during Elizabeth's early reign and the ideal model of manhood. After her father's death, Penelope's mother went on to marry Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the queen's favourite, in secret, causing Elizabeth to nickname Lettice "the she-wolf". Penelope became the ward of Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, after her father's death in 1576 and was educated in his household in Leicestershire.

Penelope was brought up in a family which had many powerful connections, such as her uncle, William Knollys, who held important positions at the courts of both Elizabeth and James I. Penelope began her career at court in 1581, accompanied by her guardian's wife, Catherine, Countess of Huntingdon, who was Robert Dudley's sister and Philip Sidney's aunt. The countess was notoriously Protestant, dedicating her life to the education of young women of the nobility and gentry. Of her pupils was the diarist Margaret Hoby, one of the earliest female diarists of the sixteenth century whose work survives. She recorded the daily events of her life, which consisted of activities such as prayer, housekeeping, attending sermons and general housework.

As a result of her background, Penelope was in a position to make a good marriage. There were reports, during Penelope's younger life, that she was to marry the poet Sir Philip Sidney, a match that her father had been keen on. Sidney was a shining example of Renaissance manhood, like Penelope’s father. He possessed intellect, chivalry and bravery on the battlefield. Alongside this, he was committed to the Protestant cause, fighting in the Netherlands against the threat of the Spanish Catholics. However, Huntingdon arranged a marriage between Penelope and the wealthy Sir Robert Rich in November 1581. The marriage was a strategic alliance between the familys' wealth and court connections. The, now Lady Rich, was a reported beauty of Elizabeth’s court and became a muse for many poets. She had golden hair with dark, ensnaring eyes. She was also a highly cultivated Renaissance woman, reportedly able to speak French, Italian and Spanish fluently. It is not surprising that academics believe her to have been the influence for some of Philip Sidney’s pieces, as a result of their family connections. She is traditionally thought to have inspired his famous sonnet sequence Astrophel and Stella, containing 108 sonnets and 11 songs. Some have suggested that the love between Astrophel and Stella is reminiscent of the love between Sidney and Lady Rich, while also emphasising themes of chastity and Penelope’s reported beauty. Below is a segment from one of the sonnets that can be construed as a declaration of Sidney’s love for her.

Loving in truth, and fain in verse my love to show,

That she (dear She) might take some pleasure of my pain:

Pleasure might cause her read, reading might make her know,

Knowledge might pity win, and pity grace obtain,

I sought fit words to paint the blackest face of woe,

Studying inventions fine, her wits to entertain:

While she was a desirable and beautiful woman, her marriage was known to be unhappy. Regardless, the couple had five children together, including Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick, and Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland. As a result of her unhappy marriage, which she had protested about during her younger years, she reportedly eloped during the 1590s with Charles Blount, Baron Mountjoy, and had the first of their six children in March, 1592, a daughter, Penelope. She did, however, continue spending time with her husband and her children by Mountjoy were tolerated by her husband and brought up with the Rich children.

The 1590s was a challenging decade for Elizabeth’s rule: many of her closest companions died, the county saw an increase in famine and Elizabeth’s court was naturally ageing. Few new members entered the court, excepting the Earl of Essex, who happened to be Lady Rich’s brother. By 1595 Lady Rich’s affair with Blount was already known. However, it would be sometime before her husband brought her adulterous affair to public knowledge, as shall be discussed later in the article.

An issue that Lady Rich faced during the beginning of the seventeenth century was the treasonous affairs of her brother. While at first known to be an admirable figure of the Tudor court, Essex was known to have a tremendous number of enemies. As a young, attractive nobleman, he had a close and often misunderstood relationship with the queen. After the failure of his Essex Rebellion in 1601, Essex accused his sister of helping to overthrow the queen; essentially trying to tarnish her reputation. Unfortunately for Essex, the queen did not act on his accusations, and Lady Rich remained in favour.

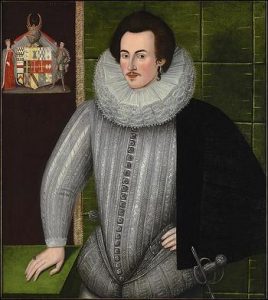

While Lady Rich led an unconventional life throughout the 1590s, she did fare remarkably well. A miniature portrait (see top of post) of her from the 1590s reveals her dressed in lavish, fashionable Elizabethan clothing. Miniatures by Hilliard were highly sought after; personalised objects that could be given as love-tokens or kept as exclusive pieces of art by the preeminent miniaturist of the period. Additionally, Lady Rich remained in good relations with the new king and queen that acceded to the throne in 1603. The Jacobean period created her lover, Mountjoy, Earl of Devonshire and she served Queen Anne as a Lady of the Bedchamber. Equally, she remained a fashionable figure of the early Jacobean court, performing in some of the most famous masques of the period. These included Ben Jonson’s lavish Masque of Blackness on Twelfth Night in 1605, where Lady Rich danced as the nymph Ocyte.

Lady Rich’s harmonious life came to an abrupt end with the unexpected divorce proceedings against her in 1605. Her husband, Lord Rich, sued for a divorce and Lady Rich in return intended to marry her lover Blount and legitimise their children. While the divorce was granted, after Lady Rich publically admitted to adulterous relations with Mountjoy, she was sadly unable to legitimise her children. As a result of this challenging situation, she decided to take the potentially dangerous move of marrying her lover in secret. As this was forbidden, King James had her banished from court. This essentially ruined the couple in terms of their social standing within courtly society and, alongside losing royal favour, they had ruined all that they had established throughout the early Jacobean period, such as Mountjoy's rise to the earldom of Devonshire. The couple died relatively close to each other, having lived in almost complete obscurity after 1605. Blount died on 3rd April 1606 and Penelope on 7th July 1607. Penelope had led an interesting and cosmopolitan existence. From associating with the court’s finest poets and courtiers, she engaged in an extramarital affair that, ultimately, ruined her position within society.

By Alexander Taylor

I studied Astrophil and Stella at university. The references to their childhood betrothal and the puns on her name leave little doubt that it’s Penelope Rich who was the object of Astrophil’s devotion – although it’s open to debate how much is courtly love and how much is real.

My mouth doth water, and my breast doth swell,

My tongue doth itch, my thoughts in labour be;

Listen then, lordings, with good ear to me,

For of my life a riddle I must tell.

Towards Aurora’s court a nymph doth dwell,

Rich in all beauties which man’s eye can see;

Beauties so far from reach of words, that we

Abase her praise, saying she doth excel;

Rich in the treasure of deserved renown;

Rich in the riches of a royal heart;

Rich in those gifts that give the eternal crown;

Who though most rich in these and every part

Which make the patents of true worldly bliss,

Hath no misfortune, but that Rich she is.

I always find it sad when I read work like this, and Wyatt’s poetry too, as it makes me “what if” about how things would have been different if these people had got together with their muses.

Yes. Astrophil and Stella is quite moving. I’m sure there was real feeling behind it. Such a shame it couldn’t be. I love Wyatt’s poetry too but what a disastrous love life he had!

Lady Penelope Rich, Duchess of Devonshire, who dared to live Life on her own terms, was my 13th Great Grandmother, I am fiercely proud to say. xoxox

My apologies for previous post—my 13th GGM was the Duchess of Devereaux, NOT *Devonshire*; that was a whole other woman. My Mac autofilled what I’d been searching & writing about. Sorry bout that~