On this day in Tudor history, 9 January 1493, Christopher Columbus recorded in his ship’s journal: "On the previous day [8th January 1493], when the Admiral went to the Rio del Oro [Haiti], he said he quite distinctly saw three mermaids, which rose well out of the sea; but they are not so beautiful as they are said to be, for their faces had some masculine traits."

On this day in Tudor history, 9 January 1493, Christopher Columbus recorded in his ship’s journal: "On the previous day [8th January 1493], when the Admiral went to the Rio del Oro [Haiti], he said he quite distinctly saw three mermaids, which rose well out of the sea; but they are not so beautiful as they are said to be, for their faces had some masculine traits."

Mermaids, as you probably know, are mythical creatures whose origin is the siren of Ancient Greek mythology. The original siren was actually a bird with a human head, but the Greeks were depicting the siren as part fish by the classical period. Homer told of the sirens using their beautiful song as a lure, and that has also become associated with the mermaid. By 1493, when Columbus’s crew allegedly saw three mermaids, the mermaid had the head a torso of a woman and instead of legs, a fishtail. They are depicted in this way in medieval manuscripts, and the British Library explains, “Mermaids and sirens also frequently appear in the margins of Psalters as symbols of temptation. In the Luttrell Psalter a siren holds a mirror and a comb, perhaps as a warning against the lure of vanity and luxury.”

Sadly, it’s thought that the three creatures Columbus’s crew saw were actually manatees. No wonder he thought they weren’t as pretty as expected!

In 1608, in the reign of King James I, explorer and navigator Henry Hudson recorded his crew seeing a mermaid off the coast of Greenland, writing:

"From the navill upward her backe and breasts were like a woman’s,

as they say they saw her, but her body as big as one of us. Her

skin very white, and long haire hanging downe behind of colour

blacke. In her going downe they saw her tayle, which was like the

tayle of a porposse, and speckled like a macrell."

The National Geographic website explains that sirenians, aquatic mammals like the three species of manatee and the dugong, whose name actually comes from the Malay for “lady of the sea”, “have long fueled mermaid myths and legend across cultures” as they are “known to rise out of the sea like the alluring sirens of Greek myth, occasionally performing "tail stands" in shallow water. Their forelimbs also have “five sets of finger-like bones” and their neck vertebrae “allow them to turn their heads”. It’s not surprising that sailors unfamiliar with these sea mammals, also known as sea cows, could mistake them for the mermaids of popular myths and legends from a distance, and I expect Hudson’s crew were exaggerating, or perhaps the hair was actually something like seaweed. Of course, they may have been drunk too!

And there weren’t just sightings. Dead “mermaids” were brought back from voyages to the New World and put on display, and, yes, they were manatees or dugongs, not real mermaids. But if you look at this dugong skeleton, you can kind of understand how it fooled sailors of the early modern era.

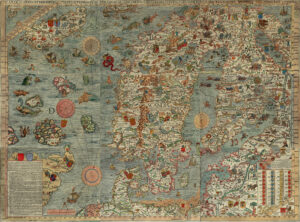

I love the Carta Marina, a map created by the Swedish cartographer, writer and Catholic clergyman Olaus Magnus and published in 1539. It was the first map of the Nordic countries to give details and place names. I love it because it has some wonderful sea creatures on it. Magnus described some of these sea creatures in his 1555 book Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus, published in English as “A Description of the Northern Peoples”, an exemplar of which was given to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, when the Swedish king was wooing Queen Elizabeth I. Magnus described a “prister” as having a face like a warthog, two blow-holes on top of its head, and a body that was 200-feet long. It also had a broad, forked tail and finned feet. Then there was the sea orm, a huge sea serpant, and a gigantic lobster. Here's a link to Magnus’s map, which you can zoom-in on to see all the wonderful sea creatures - https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ea/Carta_Marina.jpeg

If you’ve ever seen a skeleton of a blue whale, you can understand just why sailors and fishermen in times gone by believed in mythical creatures – there WERE ginormous sea creatures!

Mythical creatures weren’t just depicted on maps and in books, look, here’s one in the Armada Portrait from Elizabeth I’s reign. The painting is full of symbolism and it’s thought that as mermaids were said to tempt sailors to their fate, that this mermaid symbolises the queen’s might over the crews of the Spanish Armada. Mermaids were also said to be ill omens, foretelling and provoking disaster, and the Spanish Armada’s planned invasion of England was a disaster, with them being attacked by fire ships and being scattered by bad weather conditions. Perhaps it wasn’t the Protestant Wind of Elizabethan propaganda, it was mermaids!Mermaid sightings may seem like tall tales, but they reveal a fascinating side of early exploration, folklore, and symbolism. From Columbus’s journals to Henry Hudson’s crew, it’s easy to see how imagination and the unknown blurred the lines between myth and reality.

These stories also remind us of the power of storytelling—how legends like mermaids found their way into maps, portraits, and even royal propaganda, like the Armada Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I. Whether they were seen as ill omens or temptresses, mermaids have captivated human imagination for centuries.

Leave a Reply