On 17th February 1565, Mary, Queen of Scots met Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley at Wemyss Castle in Scotland, and fell in love.

On 17th February 1565, Mary, Queen of Scots met Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley at Wemyss Castle in Scotland, and fell in love.

It seemed like a fairy tale. Darnley was young, tall, handsome, and charming. He was of royal blood, with claims to both the Scottish and English thrones. He was the son of Lady Margaret Douglas—Mary’s own cousin—and Matthew Stuart, Earl of Lennox, whose family had spent years in exile after being declared traitors. The House of Lennox had once supported Henry VIII’s attempts to control Scotland, and by the 1560s, they were eager to regain their influence.

But for Mary, Darnley appeared to be the perfect husband - a man who could help her strengthen her claim to the English throne, provide her with heirs, and reinforce her position in Scotland. Plus she’d rather fallen under his spell – he was quite the charmer.

Yet, this love match was one of the worst decisions she ever made - a decision that set her on a course toward scandal, betrayal, and ultimately, her downfall.

At 22 years old, Mary had already lived an extraordinary life. Crowned Queen of Scotland when she was just six days old, she had spent much of her youth in France, where she had been raised in the French royal court and groomed to be queen consort to Francis II of France.

She had married Francis, when he was the Dauphin of France, heir to the throne, in 1558, and had become Queen of France in July 1559 after the death of Francis’s father, Henry II. Sadly, just over a year later, in December 1560, Francis died unexpectedly from an ear infection, leaving the 18-year-old Mary widowed and politically vulnerable. She had no choice but to return to Scotland in August 1561 - a country she barely knew, where she faced Protestant lords who resented her Catholic faith and where she had to navigate the ever-growing tension between Scotland and England.

As a Catholic queen ruling what had become a Protestant country, Mary needed a strong husband who could protect her throne and help her produce an heir. She also had her sights set on something even greater - the English crown. Mary’s father-in-law, Henry II, had proclaimed Mary and his son King and Queen of England following the death of the English queen Mary I in November 1558, and European Catholics believed that the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots had a far better claim to the throne than Mary I’s successor, the Protestant Elizabeth I, who they considered illegitimate due to her mother, Anne Boleyn’s, controversial marriage to Henry VIII, and the fact that her own father had made her illegitimate.

In 1565, Elizabeth was unmarried and childless, and if Mary married wisely, she could strengthen her claim to the English throne. But this was where everything went wrong.

Enter Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley.Darnley had been raised in England, under Elizabeth’s watchful eye, but his father, the Earl of Lennox, had been working for years to restore the family’s fortunes in Scotland. In February 1565, Elizabeth made the fateful decision to allow Darnley to travel to Scotland, supposedly to visit his father.

Mary had met Darnley before - he had been sent to France in 1559 to congratulate her and Francis II on their accession, and again in 1560 or 1561 to offer condolences after Francis’s death. But this time, when he arrived in Scotland in early February 1565, it was different.

On this day in Tudor history, 17th February 1565, Mary met Darnley at Wemyss Castle, and as the Scottish ambassador, Sir James Melville, recorded, she was instantly captivated by him. He later wrote that Mary “took well with him, and said that he was the lustiest and best proportioned long man that she had seen; for he was of high stature, long and small (meaning slender), even and erect.”

It wasn’t just his looks that appealed to her—Darnley was also well-educated, refined, and skilled in courtly entertainment. He could dance, speak multiple languages, and he had royal blood.

For Mary, Darnley seemed like the perfect match. He was a Stuart, just like her, and his English claim made him a potential king consort who could help her press her own claim to the English throne.

But there was just one problem: Elizabeth I was not happy.

As Mary and Darnley’s romance developed, Elizabeth’s attitude toward the match shifted dramatically. At first, she had allowed Darnley to travel to Scotland, but as soon as it became clear that Mary was considering marriage, Elizabeth ordered him to return to England.

Darnley, however, had other plans. He defied Elizabeth’s orders, stayed in Scotland, and pursued Mary with even greater determination. By April 1565, he was made a Knight of the Order of St Michael, and Mary began granting him lands and titles - a clear sign that she intended to marry him.

Despite Elizabeth I’s disapproval of their relationship and warnings from her advisors, twenty-two-year-old Mary married the nineteen-year-old Darnley on 29th July 1565 at Holyrood Palace. She did not seek Elizabeth’s permission to marry one of her subjects, and worse still, on 30th July heralds proclaimed that Darnley was King of Scotland, with the couple's official title being “Henry and Marie, King and Queen of Scotland”.

Elizabeth reacted to the news of the marriage by throwing Darnley’s mother into the Tower of London. And she wasn’t the only one to be angry. The marriage also infuriated the Scottish nobility, many of whom turned against Mary.

What started as a passionate romance quickly turned into a nightmare.

Darnley, once charming and graceful, became arrogant, entitled, and unstable. He demanded more power, insisting on being granted full authority as king, rather than just being Mary’s consort. A series of rows led to Mary 'demoting' Darnley and changing the legend on coinage to read “Marie and Henry, by the Grace of God, Queen and King of Scotland” instead of “Henry and Marie... King and Queen...”, and also denying him of the right to bear the royal arms. Darnley also alienated the Scottish lords with his behaviour, drank excessively, and grew jealous of Mary’s friendship with her secretary, David Rizzio.

In March 1566, less than a year after their wedding, Darnley made a fatal mistake. Not only did he begin plotting against Mary with his father and Scottish lords in exile for them to support him in his quest to be granted the Crown Matrimonial, he conspired with a group of Scottish nobles and murdered Rizzio in front of a heavily pregnant Mary. Rizzio was stabbed multiple times, with the final blow being delivered by Lord Darnley's dagger, although he was not the one brandishing it—all while the queen was held at gunpoint.

This act shocked and horrified Mary, and any love she had left for Darnley turned to hatred.

Although she later reconciled with him briefly after the birth of their son, the future James VI/James I, the marriage was doomed.

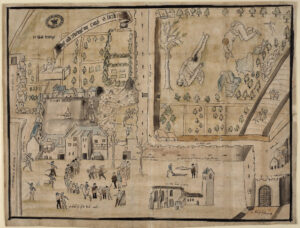

By early 1567, Darnley feared for his life, suspecting Mary’s advisors were plotting against him. He fled to his father’s estate, but Mary persuaded him to return to Edinburgh. He was recovering from an illness in his lodging at Kirk o’ Field, just a few hundred yards from Holyrood House where his wife and infant son were staying, when, in the early hours of 10th February 1567, a massive explosion destroyed the house where he was staying.The house was reduced to rubble and Darnley's body was found in a neighbouring garden, by a pear tree, beside that of his groom, with a dagger lying on the ground between them. Darnley had not been killed in the explosion, he had been strangled to death. Perhaps the explosion had been an attempt to cover up his murder.

Mary was suspected of being involved in her husband’s murder. Her decision to marry the chief suspect, James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, just weeks later sealed her fate. The scandal led to her forced abdication, imprisonment, flight from Scotland, and eventual execution in England in 1587.

Mary’s infatuation with Darnley led her down a path from which she never recovered. By choosing him, she alienated her allies, angered Elizabeth I, and tied herself to a man who would become her greatest liability.

Leave a Reply