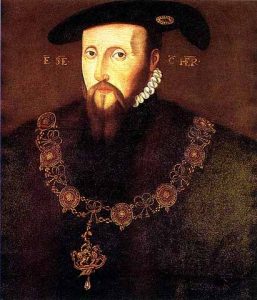

On this day in Tudor history, 22nd March 1546, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, landed in Calais to relieve the out of favour Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, in his military duties as lieutenant general there.

Hertford had been officially appointed the previous day “as the King's lieutenant in the parts beyond sea, and commander in chief of the army and armada now about to be sent thither; with authority to invade France at discretion, and to order all admirals, vice-admirals and shipmasters there.” The privy council also wrote to Surrey recalling him to England.

But what had happened? Why was Surrey being replaced with Hertford?

Surrey had been serving in the French campaign on and off from autumn 1543 and in September 1545 he was appointed lieutenant general of the king on sea and land for all of England’s continental possessions. England had captured Boulogne after a siege which ended in September 1544, but nearly lost it to the French when they attacked in October 1544. By the autumn of 1545, the privy council was advising the king to let Boulogne go, but Surrey was keen for the king to defend it and to make further conquests in France.

All looked good for Surrey in December 1545. Historian Susan Brigden explains that Surrey’s plan was to prevent the French reinforcing the fortress of Chatillon, which she explains “threatened the harbour of Boulogne and the supply of the English garrison”, and English soldiers successfully ambushed French troops and prevented supplies reaching the fortress. They also set about plans to capture it. However, disaster struck on 7th January 1546 when the English force was defeated by the French at the Battle of St Etienne. In a dispatch to Charles V, ambassador van der delft reported that the English had lost “1,200 footmen with eight English and four Italian captains” and that “the Earl of Surrey has consequently lost greatly in reputation, and there is considerable discontent at these heavy losses.”

On 11th January 1546, on hearing the news of the English defeat, and receiving no report of it from Surrey, the privy council wrote to Surrey: “The King, understanding by private advertisements from Bulloyn that Sir George Pollard is slain, and that there has been an encounter with his enemies, marvels that in so many days Surrey has not signified the matter hither. Are specially commanded to require him to signify the "circumstance of this chance," and in future to give advertisement of any such matter.” The king and his council were not best pleased!

On 15th January, in a letter to the English ambassadors, the privy council played down what had happened, writing “ But some of our men, through overmuch courage, disordered their array, and thereby seven or eight young gentlemen were lost, among them Sir George Pollard, who was "stricken on the knee with a gun out of Hardelow castle" and died within two hours, Edward Poninges, and other meaner personages. The Frenchmen will doubtless report it as a great victory, because in the misorder they got one or two of the captains' ensigns. Our men, however, gained their object”, but, as Surrey’s biographer, Jessie Childs, notes, their mention of “overmuch courage” as the cause of the English defeat was ominous for Surrey.

On 18th January, Sir William Paget, Henry VIII’s secretary of state, wrote to Surrey rebuking him for not writing to the king, but also reassuring Surrey, “His Majesty, like a prince of wisdom, knows that who plays at a game of chance must sometimes lose” and saying “he is sure that the earl had in the rearguard of the battle placed some men of wit and experience, 'which, when against all order of fight, and against the appointment of the chieftain, seeing the horse flee (as they took it), if they so thought and fled, so are not greatly to be blamed”.

Surrey continued in his service, but as Jessie Childs notes, “it was a wretched time for him, and St Etienne never strayed far from his mind.” Susan Brigden writes of how it was at that time that he “wrote two poems in female voice, transposing his own characteristic sense of isolation and abandonment into lamentations by women parted from their lovers”. He petitioned for his wife, Frances, to be permitted to join him in Boulogne, but his request was denied. Things went from bad to worse as Surrey was kept in the dark, even being sent 1000 sappers out of the blue. His exasperation is apparent in a letter to the king’s council: “Here are arrived and coming 1,000 pioneers who will consume much victual; and we have no advertisement from you how to use them”.

On 19th February, Paget wrote to Surrey informing him that Hertford was being sent, writing “the King will send an army over very shortly, and my lord of Hertford shall be lieutenant general in Bullonoys, whereby your authority of lieutenant shall cease”. He added some personal advice for Surrey: “therefore, for your reputation, you should make suit betimes for some place in the army, such as the captainship of the foreward or rearward. Thus should you gain experience and peradventure do some notable service, in revenge for the loss of your men at last encounter with the enemies; whereas, if you now tarry within a wall without authority, it would be thought abroad, either that you desired to tarry in a sure place or that your forwardness to serve was discredited here. If it please you to use me as a mean, I trust so to set forth the matter as to get you appointed to lead the foreward or rearward. And this counsail I write unto you as one that wold you well; trusting that your Lordship will even so interpret the same and let me know your mynd herein betymes.” So he was suggesting that Surrey should try and restore his reputation by serving under Hertford and proving himself. On 25th February, Paget reported that Surrey was indeed going to “lead the rearward”, so he’d listened.

Sadly, though, on 21st March 1546, the privy council wrote to Surrey recalling him. Surrey must have had mixed feelings about this – joy at the idea of see his wife and four children, but concern regarding how his service in Boulogne would be viewed by the king and his council. His children were excited by news of his return, though. In her excellent biography of Surrey, Jessie Childs includes a welcome epistle that the children’s tutor asked them to compose in Latin for their father. Although it was a schoolroom activity, Childs notes its “childlike sweetness” and “touching reverence”. They write of their “enormous joy” at his unexpected return and how “our joy is so great that the strength of this little body of mine is inadequate to express it”. They call him their “most loving father and the bravest of commanders” who “preserved the king’s interests with the greatest good faith that you could have applied”. I hope they had a wonderful reunion when Surrey returned.

Unfortunately, when Surrey arrived at court, he was, according to the imperial ambassador, “coldly received” and was refused access to the king. Things, of course, got worse for him later that year, when, in early December 1546 his former friend, Richard Southwell, gave evidence against him. Surrey was arrested and accused of improper heraldry, using arms in a painting to indicate he had a direct claim to the throne. It wasn’t true, and the real reason for his fall was his falling out with the Earl of Hertford, but the ailing Henry VIII was paranoid by this time and believed that Surrey and his father, the Duke of Norfolk, were plotting regarding the regency when the king died and his young son succeeded him. Surrey was tried for treason and executed on 19th January 1547. His pregnant wife and four children must have been devastated.

Surrey is such a fascinating Tudor chap. He served his king loyally as a soldier and was a gifted poet, and I’d highly recommend Jessie Childs’ book on him.

Also on this day in Tudor history...

Leave a Reply