Lady Alice More was born the daughter of Sir Richard Harpur and his wife, Elizabeth Ardern. Little is known of Alice’s early life, including her year of birth, but historian Retha Warnicke has dated it to in or after 1474. Alice’s first husband was John Middleton; however, the date of their wedding ceremony is unknown. Warnicke has put forward the argument that Alice was likely already married to John by the year 1492, as her father had failed to mention her in his will of the same year. This is a convincing argument; it was not particularly unusual for a fifteenth-century father to exclude his daughter from his will if she was an established member of another household. Alice’s marriage to John represented the customary ambitions of the late medieval gentry: securing wealth, status and property. The Middleton and Ardern families were related by kinship, with John being Alice’s cousin; with both parties owning a significant number of properties in Yorkshire. Additionally, Alice’s husband was a wealthy silk merchant and a member of the Mercers’ Company (a successful trade association) and the Staple of Calais (a mercantile corporation). The couple had three children: a son and two daughters, Alice and Helen, but only Alice survived infancy.

Lady Alice More was born the daughter of Sir Richard Harpur and his wife, Elizabeth Ardern. Little is known of Alice’s early life, including her year of birth, but historian Retha Warnicke has dated it to in or after 1474. Alice’s first husband was John Middleton; however, the date of their wedding ceremony is unknown. Warnicke has put forward the argument that Alice was likely already married to John by the year 1492, as her father had failed to mention her in his will of the same year. This is a convincing argument; it was not particularly unusual for a fifteenth-century father to exclude his daughter from his will if she was an established member of another household. Alice’s marriage to John represented the customary ambitions of the late medieval gentry: securing wealth, status and property. The Middleton and Ardern families were related by kinship, with John being Alice’s cousin; with both parties owning a significant number of properties in Yorkshire. Additionally, Alice’s husband was a wealthy silk merchant and a member of the Mercers’ Company (a successful trade association) and the Staple of Calais (a mercantile corporation). The couple had three children: a son and two daughters, Alice and Helen, but only Alice survived infancy.

Alice’s husband died in 1509, leaving her a moderately wealthy merchant widow. It is not known when she married her second, and more famous, husband Thomas More. More was not hesitant about marrying following the death of his wife, Jane. He had four young children and desperately required a maternal figure to head his ever-expanding household of children and adopted orphans. Like Alice’s former husband, Thomas was a member of the Mercers’ Company and was acquainted with John Middleton’s contemporaries. Equally, Thomas More was likely attracted to Alice as a result of her household qualities; her having experience raising children with her previous husband. The only surviving evidence for how soon after Jane More’s death Thomas wed Alice is in a letter written in 1535 by the parish priest, Father John Bouge. He recalled that within a month after Jane’s funeral, Thomas came to see him one Sunday night with a licence from Cuthbert Tunstall, commissary-general of the prerogative court of Canterbury, to dispense with the banns for his marriage to Alice Middleton. Reasons for the relative scarceness of More’s wedding ceremony could be the result of his own doing. Unlike first weddings, elaborate festivities and celebrations did not accompany subsequent weddings. There was still a certain prudence concerning second marriages, as they could be labelled bigamous and unholy by contemporaries; significantly in the cases of women remarrying.

Lady More and her second husband initially lived together at the Old Barge in Bucklesbury; having moved there sometime between October and early November 1511. As a result of their large family - the Mores’ residence also housed their foster daughter, Margaret Giggs, and Anne Cresacre, an orphaned heiress who married Thomas’s son, John - the family relocated to Chelsea, London, in 1525. As a result of Thomas More’s advocacy of scholarly pursuits, his household became renowned as London’s leading institution for the humanist style of education; significantly the education of women. In 1521, the Dutch scholar and humanist, Erasmus, praised Lady More’s supervision of her stepdaughters’ education in a letter to the French scholar, Guillaume Bude. He stressed that her abilities in their education was the result of “mother-wit and experience”, rather than academic training. Thomas More’s daughter, Margaret, became a prominent figure in scholastic society, being the first non-royal woman to publish a translation. She later became distinguished as a celebrated translator and devout upholder of Roman Catholicism throughout the precarious, impending religious reformation of the early sixteenth century.

Upon Thomas More’s imprisonment in the Tower of London, for not signing the oath for King Henry VIII’s Act of Supremacy, he was visited by the female members of his family on several occasions. Lady More pleaded with her husband, arguing that he should retire with his family to Chelsea and sign the oath for the preservation of his mortal life; evidently, Lady More was fond of her husband. Margaret Roper (his daughter, now married) and her father secretly shared letters during his confinement; most of his eight surviving letters addressed to Margaret affectionately mention his wife. Similarly, he refers to Lady More as his “good bedfellow”, which may suggest that a certain degree of intimacy existed between the two during their marriage. Two months before her husband’s execution, Lady More wrote to Thomas Cromwell, then secretary to King Henry, listing her grievances. These included: selling her effects to fund her household and paying for her husband’s upkeep in prison. Cromwell was the ideal candidate to turn to; he was a self-made man and a trained lawyer who would rise in the king’s favour during the mid-1530s.

After her husband’s execution in 1535, the crown granted Alice an annual annuity of £20; a kind gift considering that her husband was deemed a traitor. Additionally, the king allowed her to possess, until 1543, a lease of some lands in Battersea obtained by her husband in 1529.

Lady More’s death date has been a source of debate among academics, with scholars placing it between 1546 and 1551. However, experts have suggested that 1551 was the likely year of death, as an entry in the Land Revenue Miscellany Book, 212, noted on April 25th, 1551, that an Alice More had died.

In conclusion, Lady Alice More was an ideal wife by sixteenth-century societal standards; raising successfully, well-educated children and upholding the customary, feminine virtues expected of a pious woman.

Alice’s posthumous reputation has hitherto witnessed a series of slanderous and unfair representations. She has been referred to as a ‘Harpy’ like figure; referencing her purported unpleasant and rapacious behaviour. (In Greek mythology Harpies are violent and aggressive half-bird, half-woman monsters.) Historiography has tended to perpetuate this myth, specifically the literary academic Percy Allen, in 1906. William Roper, her step-son in law, married to More’s daughter, Margaret, had, like later historians, been critical towards Alice’s life. He characterised her as a materialistic and earthly woman, void of the spiritual convictions of her husband. Nicholas Harpsfield, for whom Roper prepared his account, similarly began his biography of Thomas More by slandering Alice’s character. He stated that Thomas wed her more for supervising his offspring than for “bodily pleasures.” While Alice’s experience of household management, and successful raising of children, were desirable, Thomas was fond of his final wife and provided a comfortable environment for her. This included an exceptional education, a variety of music lessons and a secure position in society as the wife of the Lord Chancellor. Additionally, as stated earlier in this article, Thomas More spoke affectionately of his wife during his imprisonment, and once referenced her as his “good bedfellow.”

Retha M. Warnicke is one of few modern historians to revaluate Lady Alice More’s life, debunking the myth that she was a cutthroat woman. Warnicke stresses that Allen’s argument, that represented Alice as ‘hook nose Harpy’, is unfair. Instead, Alice’s marriage to Thomas More was entirely conventional. She brought with her a proportionate widow’s jointure from her previous marriage, alongside inheritance and many household skills that were deemed desirable by sixteenth-century standards. Allen’s argument is derived from a letter from humanist scholar, Andreas Ammonius, addressed to his friend Erasmus. It was dated October 27th, 1511, while Ammonius was lodging at the More household at the Old Barge. He complained to his friend that he would no longer have to deal with English housekeeping, which he criticised, followed by five untranslatable Greek words. Allen believed that these Greek words were about Alice’s hook-nosed or beak-like appearance and that Ammonius was somehow complaining about her hospitality.

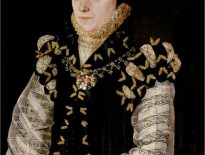

Regarding her purported hook-nosed appearance, the portrait of Alice More from the studio of Hans Holbein the Younger in no way suggests that Alice was the unattractive woman of Allen’s study. Rather, it reveals her as a modestly dressed women reading a book. What furthers Allen’s inaccuracy is the fact that the hook-nosed theory is based on several Greek words that are not easily translated; rendering it, in historian Ruth Norrington’s view, “grossly exaggerated.” This is not to suggest that Lady More was a particularly beautiful woman; while the Harpy theory has been debunked, Thomas More did inform Erasmus that Alice was “old and not pretty.” Lady More was in her mid-thirties by the time of her second marriage, which by sixteenth-century standards was not particularly young. This is not to suggest she was ultimately unattractive, but that her physical appearance was unlikely to have been Thomas More’s primary motivator in marrying her, rather, he acknowledged the benefits of marrying a skilled and wealthy widow.

By Alexander Taylor

Picture: Lady Alice More from the studio of Hans Holbein the Younger.

I really enjoyed this article, there are so many myths about Alice that it was refreshing to learn a little bit about her. If possible I would like to know more about Alice her life and the relationship she and Thomas had together.

Hi Lynne – indeed, Alice is an unfortunately maligned figure in Tudor history. I recommend Retha M. Warnicke’s book, ‘Wicked Women of Tudor England’, for further information on her. It examines Alice’s upbringing, first marriage and overall reputation. Similarly, Peter Ackroyd’s biography of Thomas More is an enlightening read.

Thank you I’ll look them up 🙂

It is very interesting to meet Alice Middleton in her own right and not just in the shadow of her great husband, Thomas More. It is very rare that women in the sixteenth century for a woman to step outside of their husbands career and lives. She was a good manager of More’s vast and expanding household and she is noted here as supervising Meg’s education, which suggests that she had some degree of classic education herself. She was a woman of whit and good cheer, was warm and loving and she appears as a vast personality.

It is so interesting how myths start. Even one ineligible letter can completely tarnish a person’s reputation for 500 years. This is a very well written summary of her life, without bias or fake news. 🙂 Thank you – always fun to read about Tudor women.