Thank you to the University of Warwick for sending me this interesting article by Kevin Butcher, Professor of Roman History. If you've been watching our Tudor Society Advent Calendar videos, you'll know that I mentioned Saturnalia in the talk I did on the Lord of Misrule tradition.

Thank you to the University of Warwick for sending me this interesting article by Kevin Butcher, Professor of Roman History. If you've been watching our Tudor Society Advent Calendar videos, you'll know that I mentioned Saturnalia in the talk I did on the Lord of Misrule tradition.

Whilst we celebrate Christmas, over 2000 years ago the ancient Romans were busy with their own winter festival; Saturnalia. Over-eating, drinking, singing, gift-giving, pranks, singing stark naked and theatrics were all associated with the festival, which was the most popular holiday of the year. Kevin Butcher, Professor of Roman history at the University of Warwick, says that the 25th December was also celebrated by Romans.

Partying, pantomime, feasting and gift-giving are all established traditions of the Christmas season. At the same time of the year over 2000 years ago, Romans had the very same customs in celebration of a different festival – Saturnalia.

Originating as a farmers' festival dedicated to Saturn, the Roman god of agriculture and the harvest, Saturnalia began on the 17th December and lasted between three and seven days.

As with our Christmas celebrations, it was a period during which all work and business stopped (Lucian, Saturnalia, 13) – and was the most popular holiday of the year with the poet Catullus calling it ‘the best of days’. (Catullus, Carmen, 14).

During Saturnalia Romans broke away from standard behaviour and dress and even engaged with role-reversal. Women, children and slaves enjoyed more freedom allowing everyone to socialise and celebrate together (Lucian, Saturnalia, 13) – greeting each other with the popular seasonal greeting ‘Io Saturnalia’ (pronounced Yo). (Martial, Epigrams, 11.2)

Saturnalia provided an opportunity for Romans to indulge themselves in excessive eating, drinking, and gambling which were all traditionally seen as vices. (Martial, Epigrams, 11.2, 11.15, Lucian, Saturnalia, 2, 9) Public events and feasts were widespread with banquets held in the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum. Accounts describe how people would dress smartly and bring with them bread baskets, white napkins, wine and other ‘elegant eatables’. (Statius, Silvae, I.6.1)

Musical entertainment was provided by foreign slaves as Statius writes ‘in one group Lydian ladies clap, elsewhere are cymbals and jingling Gades, elsewhere again troops of Syrians make din’. (Statius, Silvae, I.6.1)

Later, the 25th December had great significance as the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti or ‘Birthday of the unconquered sun’, celebrating the cult of the sun god Sol, a festival which was later associated with the birth of Christ.

“The first evidence for the date of 25th December”, according to Professor Kevin Butcher, of the University of Warwick’s Department of Classics and Ancient History, “is in a Roman calendar of AD 354, where it is noted that this is also the day of the birthday of the Unconquered Sun”. This date in Late Antiquity comes only around a century before the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century.

How this day came to be considered the date of the nativity is unknown but Professor Butcher says “it is possible that the emperor Constantine (AD 307-337) had some influence, since before his conversion to Christianity he was a keen devotee of the Unconquered Sun, a god who is commonly depicted on his coins”.

One poem of Statius recounts the spectacle of a Saturnalian feast in the colosseum under the emperor Domitian. This December was ‘wine-soaked’ and the ‘tipsy feast’ was accompanied by amusing pranks. Among the theatrics on offer were virtuoso combats between women and dwarves during which both sides would ‘deal wounds and mingle fists and threaten one another with death!’ (Statius, Silvae, I.6.1)

During the imperial period, there are references to a King of the Saturnalia whose ridiculous demands had to be obeyed by other guests. Lucian gives the examples of singing stark naked and being pushed head-first into cold water with a face full of soot – an echo of today’s Christmas pantomimes. (Lucian, Saturnalia, 2)

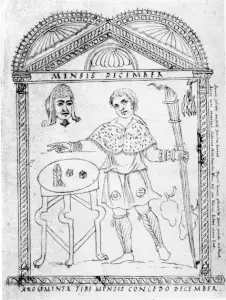

An illustrated Christian manuscript of AD 354 called the Calendar of Philocalus offers a personification of December which illustrates several aspects of Saturnalia. The torch represents the nocturnal celebrations, the dice alludes to gambling and games, the birds are an example of a gift and the mask symbolised the festive entertainment.

Interestingly Statius chooses to end his account pondering the legacy of Saturnalia, eventually concluding that the sacred holiday will ‘endure throughout all time’. (Statius, Silvae, I.6.1) Considering that many Roman traditions have survived and are part of our modern Christmas he was correct.

Professor Butcher, states that there is no explicit connection between the Christmas and Saturnalia festivals despite some similarities and says ‘it's not even clear whether the earliest Christians celebrated an anniversary of Christ's nativity’.

For any inquiries about this article or the work of Professor Butcher, please contact: Kim Ingram, Tel: +44(0)24765 75601, Email: [email protected]

Sounds like some modern Christmas parties, especially at Uni ho ho!!