Thank you to Loretta Goldberg, author of The Reversible Mask: An Elizabethan Spy Novel for joining us today and sharing this excellent guest article on the Siege of Antwerp.

During World War II, Sir Winston Churchill said, "In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies." Illusion was a tactic used in 1944 to deceive the Nazis about where the allies would land; many historians believe that the Normandy beachhead held because of the deception. 336 years earlier, in 1588, England faced invasion by Spain with its Armada of 120 ships and 20,000 troops that were meant to be supplemented by comparable forces from Spain’s soldiers and barges in the Netherlands (known as the Army of Flanders.) Illusion then also saved England.

The seeds for this nation-saving illusion were planted three years earlier, during the siege of Antwerp. Dutch Protestant rebels, aided by some money from England and friendly Protestant units from other states resisted the Spanish army’s siege for nine months. Spain won the siege of Antwerp, but what the Dutch threw at them with three terrifying and bamboozling new weapons so devastated Spanish morale that the memory of them in 1588 caused Spanish lookouts and captains to confuse manageable, traditional English weapons with the new Dutch weapons. Dread caused the Armada captains to break formation against orders, offering easy targets to waiting English warships and led to the ultimate defeat of Spain’s invasion enterprise.

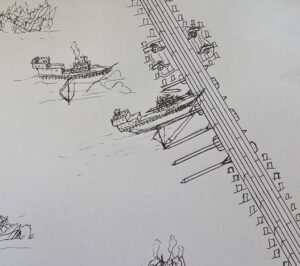

I have always been fascinated by the grip Dutch creativity had on the Spanish heart and mind of the time. The reason I’m writing this post is that contemporary images exist of the first two new Dutch weapons, but not the third. Tantalizingly, the Spanish commander, Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma and Governor-General of the Netherlands, described this third weapon in his journal. A reader of my first novel, The Reversible Mask: An Elizabethan Spy Novel, has drawn me a period-appropriate image of the third weapon. Retired civil engineer of roads and bridges, Mark Getchel is also an historian of his own family’s 400-year-old military history.

During the siege, Parma plaintively bemoaned the Dutch “industrious genius and the machines which they devise. Every day we are expecting some new invention…I confess that our merely human intellect is not competent to penetrate the designs of their diabolical genius, Certainly, most wonderful and extraordinary things have been exhibited, such as the oldest soldiers here have never before witnessed.”1 When Parma’s engineers examined the debris from the exploded new weapons they couldn’t replicate them. It’s as if Parma perceives his enemy as a superior, unknowable species of humanity. It was the number and variety of new weapons that sapped long-term Spanish morale.

Background

The siege of Antwerp occurred 18 years into a rebellion by Dutch Protestant parties against persecution by their Catholic Spanish rulers. The Hapsburg dynasty had married into ruling the valuable Netherland provinces during the fifteenth century. Philip II, the king of Spain, governed an empire encompassing the Americas, East Indies (absorbed when Philip inherited Portugal), the Catholic states of the Holy Roman Empire in Europe (about half of the states in the Holy Roman Empire had adopted Reformation religions since 1517 and repudiated Philip’s rule) and several Italian client states. Philip was a fervent burner of religious heretics.

The Dutch rebels were tougher to suppress than indigenous populations of the New World; the rebellion would last 80 years until the Netherlands won independence from Spain in 1648 as The Dutch republic. In 1576, ten years into the rebellion, 16 predominantly Protestant-governed provinces declared independence as the United Provinces of the Netherlands and established a separate governing body, their States General. So the war was both colonial and religious. Across the seas in England, the Protestant queen Elizabeth tried to mediate a peaceful settlement in the 1570s. A cautious minimalist, Elizabeth resisted internal pressure to intervene on the rebel side, but didn’t prevent private money or volunteers from helping the Dutch cause. In 1584, she believed that Antwerp would hold, an optimism not shared by her Privy Counsellors. If Antwerp were to fall, the threat of a Spanish invasion of England would exponentially increase.

Antwerp in 1584 was a major city whose population was literate by the standards of the day, and quite diverse, including Protestants, Catholics, a few Anabaptists and free thinkers, merchants, bankers and artisans. Opposing Parma were the city’s commanders Burgomaster Sainte Aldegronde, a poet and polemicist, and Admiral Jacobson of Antwerp’s fleet of ships. Although the Dutch had technological superiority, they lost Antwerp because of bad tactical decisions that prevented them from taking advantage of momentary Spanish weakness that their new weapons caused.

The Siege

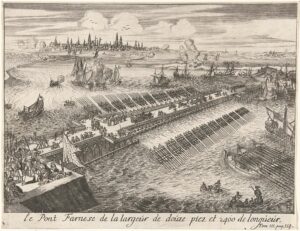

By autumn 1584, Parma’s army had gained control of the Kouwenstein Dyke on Antwerp’s landward side and begun to seal off the city’s access to the sea by building an improbable bridge across the entire 2400-foot width of the River Scheldt on the seaward side. In attempting this feat, Parma expanded the era’s understanding of what was possible in bridge building. Despite attacks by Dutch skirmishers, he built two new forts on the river’s banks and a bridge of linked, fortified barges supported by stout pilings, finishing the job in eight months.2

How could any weapon Antwerp’s defenders devised under siege conditions reach this bridge, let alone blow a big hole in it? That two of their new weapons accomplished this, killing an unprecedented number of Spanish soldiers, stunned the enemy. The Dutch rebels deployed the first kind of new weapons from April 4 to late May 1585, a second weapon in late May 1585 and the third weapon in July 1585.

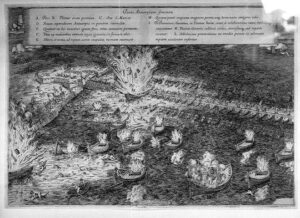

Federigo Giambelli, a Mantuan engineer who’d joined the Dutch side, the Antwerp clockmaker Bory and a mechanic named Timmerman combined their talents in a secret plan to make the first self-detonating bomb ship. Giambelli had been granted two 70-ton cargo ships (useless to merchants during a siege) and plenty of gunpowder. Bory had invented a clock that could be pre-set to light a wick to a lamp, the first self-lighting lamp. As it was expensive, only a few aristocrats had them. The three men applied this technology to a clock pre-set to strike a flint that would fire a wick leading to the bomb. Timmerman’s role is not clear, but Giambelli developed a proprietary recipe for gunpowder he wouldn’t share with his patrons. His goal was to make a bomb that would explode sideways and not up when it hit Parma’s bridge. It did.

The two ships, Fortune and Hope, had stone pyramid cones on the deck, filled with anti-personnel implements: stones, chain shot, stakes, harpoons, halberds and axe heads. In the hold there was a large marble chamber filled with seven thousand pounds of Giambelli’s specially grained gunpowder. The marble chamber was covered by a tin roof, the whole apparatus covered by light wood planks, bricks and piles of wood. The deck wood piles were meant to make them look like weak fireships. Hedging their bets on Bory’s self-lighting clocks, Giambelli used a slow-burning wick in Fortune while in Hope he used Bory’s clock with an hour’s time delay with a modified fire-arm flintlock to fire the wick. On the night of April 4-5, skeleton crews on both ships lit small fires on deck and fled.

To ensure that the bridge would be crowded with defenders at the right time, Giambelli sent 32 small fireships ahead of Fortune and Hope, bringing all available Spanish troops to the riverbanks and bridge. They repelled many of the fireships with poles and nets. The two bomb ships drifted behind the fireships showing minimal fire on deck. Before reaching Parma’s bridge, Fortune ran aground on sand. Sensing no danger, Spanish soldiers climbed aboard, curious. The ship exploded, killing everyone aboard and hurtling flaming debris to fill the air.

The Spaniards had no time to grasp what had happened and warn the multitude on the bridge. Hope struck the bridge with a crack of wood and iron on wood and iron then silence. Nothing happened. Laughing Spaniards filled the decks, pinging the odd stone cone with their axes. In seconds 1,000 were killed, a 200-foot breach was blown in the bridge, many parts of the construction were gone. Shredded body parts flew through the air and Parma was knocked unconscious. Boiling river water burned many to death. Some survivors on one bank were flung skywards and woke up on the opposite bank. The bomb’s energy even disrupted the ebb tide: water was sucked out fast and roared back in a ferocious flood. Over a mile away large stones from the bombs crashed through farmers’ roofs, and a marble slab penetrated the earth to the depth of a man’s height.3

The Dutch plan was to send up a flare signalling a waiting Zeeland rebel fleet that the new weapons had made a breach in the bridge so the fleet could sail through and break the siege. Now came the first of the Dutch rebels’ tactical mistakes. There was no flare. Admiral Jacobson didn’t send scouts to assess the damage to the bridge for two days. Delay allowed the Spaniards to fake the look of repair; the Zealand fleet stayed put.

In the attack on April 4-5, Giabelli employed fireships as decoys for the Hellburners. Three years later, lookouts and captains on the Spanish Armada ships assumed approaching English fireships were Hellburners, causing a panic flight that doomed Philip’s invasion of England.

Fireship4 versus Hellburner5 below:

- Fireship

- Hellburner

Fireships had blazing fires on decks, sails and rigging, set by crews who jumped into the sea for boats waiting to row them back safely to their lines. The goal was to spread fire to wooden enemy ships, and if enemy ships were full of ammunition and gunpowder all the better. But fireships could be repelled by poles, axes and dousing with water. Hellburners had little visible fire on deck and were self-detonating. They had no visible crews near impact.

After April 5, Giambelli kept sending fireships and smaller Hellburners at the bridge, Parma described life there: “We are always upon the alert with arms in our hands. Everyone must mount guard, myself as well as the rest…almost every night, and the better part of the day.” On May 7, an attack by the Zealand fleet was meant to be supported by Antwerp’s fleet. In a second tactical mistake, Dutch communication failed. The Antwerp fleet stayed put and Pama beat off that attack.

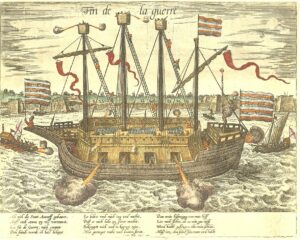

On May 26 the Spaniards saw the Dutch rebels’ second invention leave port to support a coordinated land and sea assault to retake the Kouwenstein Dyke. Fin de la Guerre had a miniature castle in the center, four masts and bulwarks ten inches thick. At the water line corks and empty barrels were supposed to keep it afloat. 20 cannon were protected by iron plates; the ship hosted 1,000 musketeers in bullet-proof crows nests. But when it left Antwerp it ran aground on a sandbar at Orldam.6

Giambelli had always derided the monster ship as “River’s Bottom,” warning that its mathematics were flawed, but no one else, including the Spaniards who knew it would deploy against them, knew it was destined to fail. Until it did. Relieved Spaniards called it Bugaboo when they captured its artillery two days later, while crestfallen rebels called it Lost Penny, Antwerp Folly, Elephant.

Despite the humiliating flop of Fin de la Guerre, the effort to retake the Kouwenstein Dyke almost succeeded. Dutch and allied troops, including English volunteers, supported by rebel ships commanded by Justin of Nassau, defeated the Spanish garrison holding Kouwenstein Dyke and demolished part of the dyke. One relief ship sailed through to exultant whoops by the rebels. Now came the third Dutch tactical mistake. Craving gratitude from his citizens, Sainte Aldergonde celebrated prematurely. He and many of his senior officers left the battlefield for a banquet and an affirming bell ringing in town. With Parma’s men over three miles away, Sainte Alderginde underestimated the Spanish will to counterattack. But quick reaction was Parma’s strength; he prevailed later that day and the siege continued.

By July 1585, Giambelli needed new ideas to break the siege. Too many fire ships continued to be blown by the wind onto debris or sandbars. Even the heavier Fortune had grounded on a sandbar. He was running out of crews and had lost the element of surprise that made Hope’s detonation so cataclysmic. On the suggestion of an unnamed German sailor, Giambelli built two small Hellburners powered solely by a single underwater sail attached to the hull, theoretically creating a drag that would catch the current. One ship had hooks to grapple the bridge as it exploded. It isn’t known which of the ships was more heavily armed, but one of them had four thousand pounds of explosives, less than the seven thousand pounds on Hope and Fortune. The ebb tide of River Scheldt was strong in the sixteenth century, an era often referred to as the “little ice age.” The German sailor’s theory turned out to be feasible. Both ships reportedly approached the bridge straight and fast without being diverted by eddies or wind. Even though the Spaniards were primed to expect anything by now, it must have been an astounding sight: crewless, self-propelling and self-detonating. Both ships damaged the bridge, but they hadn’t contained enough explosives to again break the siege.

In August 1585, with food running low and pressure from Antwerp’s Catholic citizens, Antwerp’s leaders began negotiations with Parma to surrender. By the standards of his day, Parma wasn’t a brute and eschewed mass reprisals. But it was a hard-won victory for Parma. In his journal during the siege, he is clear that it was the number and variety of new weapons that sapped Spanish morale. He maintained a wary fear of his opponents’ “industrious genius” and “obstinate dog” temperament. In the hand-to-hand fighting with the remnants of Sainte Aldergonde’s units holding Kouwenstein dyke, he noted that the last men to flee were English volunteers.

Fast forward to August, 1588

After six days of indecisive fighting in the English Channel, the impregnable crescent formation of 120 Spanish war and transport ships waited outside Calais for Parma’s forces in Dunkirk to join them. The English commanders, Admiral Charles Howard, 2nd Baron Howard of Effingham, Sir Francis Drake, Sir Martin Frobisher and Sir John Hawkins had ships plying to and fro in the Straits of Dover. They were in despair, having thrown the best Elizabeth’s navy had in gunnery at the enemy to little effect. Spanish admiral Don Alonso Pérez de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, expected an English attack and placed small boats around the perimeter of his formation to repel fireships. He ordered his subordinates to keep formation.

The mood among the Spanish captains could have been buoyant; they’d survived six days of fighting in the English Channel with only a couple of ships lost. But two pieces of news sabotaged their confidence. Parma, who hadn’t known of the Armada’s progress, sent word from Dunkirk that he needed two weeks to join them, while the mayor of Calais town, neutral in the war, advised Medina Sidonia that their anchorage was dangerous. If a violent storm hit them, their ships could be dashed against the high cliffs. Still, orders were to keep formation.

Near midnight, Spanish lookouts saw six large burning ships gliding toward them on the tide. Terror gripped the Spanish soul. The lookouts saw death coming at them and yelled “Hellburners!” over and over again, generating a contagious panic and shambolic flight. The English fireships burned out on water or on the beach and did no damage at all. Illusion; panic; fatal mistake. Illusion for the Spaniards proved more powerful than six days of gun battles. A fortune in Philip’s iron sank to the seabed. Spanish ships lost manoeuvrability, some crashed into each other and the rest is well chronicled in children’s history books. A north wind pushed the Armada north, and without cables or anchors they couldn’t regroup. With the Armada’s formations broken, English warships were able to inflict significant damage on many Spanish ships during the next morning’s battle. Sailing home around the western coast of Ireland, most of the ships were wrecked and many of the troops perished.

From the siege of Antwerp in 15854-5 until the Spanish Armada in 1588, the canny Elizabeth fed Spanish fear. Giambelli wasn’t a natural ally to the Protestant coalition. A Catholic Mantuan with a brilliant mind, short height but giant ego, he went to Spain and first offered his designs for defensive walls to his overlord, Philip, but Philip didn’t receive him. Insulted, Giambelli went to England where he received an audience with Elizabeth, telling her Privy Counsellors that the next time the Spaniards encountered him they would “remember his name.” Elizabeth liked his defensive ideas and gave him a subsidy and letter of recommendation to the Antwerp burgomasters, where he’d be “closer to the Spaniards on whom he wished to avenge himself.” The Antwerp burgomasters didn’t approve any changes to city walls but gave him two cargo ships for a secret new weapon. When Antwerp surrendered Giambelli fled to England, since the Spaniards now “knew his name.”

In England, he asked to build Hellburners while not sharing his proprietary recipe for gunpowder. Elizabeth refused. She said that England didn’t have enough reserves of gunpowder, and, despite the bombs’ new destructive power, they hadn’t saved Antwerp. Elizabeth may have also had an unspoken reason. Since her youth, she’d had to dodge plots by her relatives to bring her down, and survival had given her an exquisite understanding of male vanity. She must have realized that a Catholic who owed his loyalty to Philip, and was so quick to take offense and turn against him, could turn against her too. To assuage his ego and keep the Spaniards guessing. she made sure that he was seen in the company of the “best persons in the realm” surveying England’s defences. He met Sir Francis Drake. Philip had spies in London, so the optical tease she gave them by a sighting of the inventor of the diabolical machines with Spain’s most dreaded naval enemy, El Draco, offered a useful deception tactic.

Final Irony

Elizabeth employed Giambelli from 1585 to 1602, assessing how to bolster defensive fortifications. Since England wasn’t invaded, his defensive ideas were only tested once, when Spanish Armada ships were expected to penetrate the River Thames in 1588. Giambelli constructed a boom across the Thames consisting of a chain supported by 120 ship masts. It broke at the first flood tide. The Virgin Queen usually didn’t “look through her fingers” at failures by men of lower rank that cost her money, but she continued to employ the highly-sensitive Mantuan.

It’s fun to play what if and speculate about alternative history. If Philip had granted Giambelli an audience, would the Spanish Armada have landed in England and forced it back to Catholicism? If Giambelli had understood that his sovereign had a mental disorder undiagnosed until centuries later-- severe obsessive compulsive disorder--would Giambelli have reacted to Philip’s indifference to his ideas and felt pity rather than rage? To the despair of Philip’s counsellors, their king could immerse himself for weeks resolving a dispute over which monk was entitled to sleep in what size cot in a monastery he was endowing, while dispatches from his military commanders went unanswered. His counsellors had no name for this workaholic trait, which Philips’ biographer Geoffrey Parker recently suggested illuminates how Philip made choices. Small personality quirks can have great consequences, which is the charm of history.

Were the Dutch Weapons Fantastical or Ahead of their time?

Hellburners weren’t replicated for many centuries. It wasn’t because they didn’t work, but because the amount of gunpowder needed for a single explosion was too costly.

Fin de la Guerre. What did the Dutch get wrong? According to naval historian Captain Roger Crossland, the theory wasn’t completely wrong. But a deep draft and extraordinary amounts of cork would have been required to float it. And that wouldn’t have accounted for the problems of recoil had the ship’s cannon ever fired. It wasn’t until the Crimean War that the Russians successfully deployed a mortar ship with four anchors spread like an X to absorb the recoil of large guns.

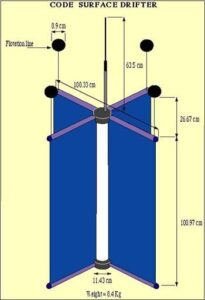

Hellburners propelled by an underwater sail. The utility of underwater sails wasn’t fantastical either. Here’s the design that the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration uses to accurately measure currents and tides.

So the Dutch were ahead of their time, and their vision spooked their more pragmatic enemy to the extent that it materially impacted the war between Spain and England.

Loretta Goldberg's The Reversible Mask

For fans of Philippa Gregory, John le Carré, Alison Weir, and C. J. Sansom:

For fans of Philippa Gregory, John le Carré, Alison Weir, and C. J. Sansom:

Summer 1566. A glittering royal progress approaches Oxford. A golden age of prosperity, scientific advances, exploration and artistic magnificence. Elizabeth I's Protestant government has much to celebrate.

But one young Catholic courtier isn't cheering.

Conflicting passions--patriotism and religion--wage war in his heart. On this day, religion wins. Sir Edward Latham throws away his title, kin, and country to serve Catholic monarchs abroad.

But his wandering doesn't quiet his soul, and when Europe's religious wars threaten his beloved England and his family, patriotism prevails. Latham switches sides and becomes a double agent for Queen Elizabeth. Life turns complicated and dangerous as he balances protecting country and queen, while entreating both sides for peace.

Intrigue, lust, and war combine in this thrilling debut historical novel from Loretta Goldberg. Find out more at http://getbook.at/reversiblemask

About Loretta

Loretta Goldberg writes historical literary fiction with battle scenes. She loves this genre because she finds in history’s frames, where events have beginnings and endings, a magical mirror in which we can see ourselves more fully. Her debut novel, The Reversible Mask: An Elizabethan Spy Novel, won the International Firebird Book Award in Historical Fiction and New Fiction in 2023. It also won a Book Excellence Award Finalist in 2019. Her second novel, Beyond the Bukubuk Tree: A World War II Novel of Love and Loss, won an International Firebird Book Awards in 2023 for War Fiction, the Storytrade Book Award in 2024 for LGBTQ Fiction and a Literary Titan Gold Book Award in 2024 for Fiction. Beyond the Bukubuk Tree is a Finalist in the Hemingway Book Award novel for Wartime Fiction 2024, the contest ongoing.

Loretta Goldberg writes historical literary fiction with battle scenes. She loves this genre because she finds in history’s frames, where events have beginnings and endings, a magical mirror in which we can see ourselves more fully. Her debut novel, The Reversible Mask: An Elizabethan Spy Novel, won the International Firebird Book Award in Historical Fiction and New Fiction in 2023. It also won a Book Excellence Award Finalist in 2019. Her second novel, Beyond the Bukubuk Tree: A World War II Novel of Love and Loss, won an International Firebird Book Awards in 2023 for War Fiction, the Storytrade Book Award in 2024 for LGBTQ Fiction and a Literary Titan Gold Book Award in 2024 for Fiction. Beyond the Bukubuk Tree is a Finalist in the Hemingway Book Award novel for Wartime Fiction 2024, the contest ongoing.

Her characters are flawed strivers, often in love with the wrong person or at odds with social norms, or both, who get caught up in history’s iconic struggles and risk all to make a difference. Kings, queens, maids, Ottoman diplomats, spies, farmers, nurses–they all have nuance. Her world view evolved from living the highs and lows of being a professional pianist, tempered by the pragmatism of years as an insurance agent and registered representative with employee payrolls to meet, and diverse jobs she held along the way, including house painter, advertising bill collector and telemarketer.

An Australian-American, she earned a BA (Hons.) in English literature, Musicology and History at the University of Melbourne. She came to the USA on a Fulbright scholarship to study piano. Her CDs of new music are in over 700 libraries (See Discography). She premiered an unknown work by Franz Liszt on an EMI HMV (Australian Division) album, and her edition of the score for G. Schirmer is in its third edition.

Her published non-fiction consists of articles on financial planning, arts reviews and political satire. She lives with her spouse, commuting between New York City and Chester, Connecticut, where she enjoys family, friends and colleagues. For the New York Chapter of the Historical Novel Society, she started the chapter’s published writer public reading series at the Jefferson Market Library, New York City, and is the chapter’s current chair. She is a member of The Authors Guild and National League of American PEN Women.

NOTES

- Parma’s journal on his battles in the Netherlands were published in a seventeenth-century history by Jesuit historian Famiano Strada. Strada had what we call today exclusive access to Parma’s papers in order to write a definitive account of the conflict between the Dutch rebels and their Spanish rulers from the perspective of one of Spain’s most celebrated generals. Strada published De bello Belgico decas primain 1617 and De bello Belgico decas seconda in 1647. The volumes were translated into English and published in London by Sir Robert Stapylton in 1650 as The History of the Low Country Warres.

- Hooghe, Romeyn de - Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

- Hellburners at Antwerp by Famiano Strada.

- Wikipedia, cropped: 17th century fireship. The burning of the 4 at the Battle of Solebay, 28 May 1672.

- Cropped: Engraving from the eighteenth century depicting the explosion of one of Giambelli’s “hellburners” at the bridge of boats of the Duke of Parma in the Siege of Antwerp (1585) . https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/hellburners-weapons-destruction.html

- Frans Hogenberg - https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/RP-P-OB-78.775 Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Leave a Reply