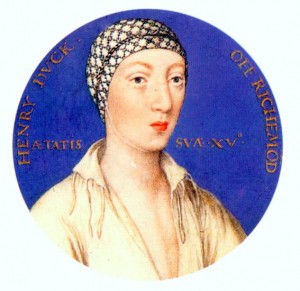

Henry Fitzroy

In 1519, Bessie had been sent by Cardinal Wolsey to reside at the prior’s house of the Priory of St Lawrence, in Blackmore, before her pregnancy became visible. It is not known when Bessie gave birth to Richmond, or when the child was christened. His birthdate is traditionally given as 15th June 1519, but Elizabeth Norton, historian and author of “Bessie Blount: Mistress to Henry VIII”, wonders if Richmond was actually born on 18th June because Cardinal Wolsey was with Henry VIII on that day and then although he was expected at Hampton Court Palace on 19th June he disappeared until 29th June. It was Wolsey who acted as Richmond’s godfather and who organised Bessie’s confinement, so it is reasonable to assume that he went to Blackmore. Also, as Norton points out, Henry VIII chose 18th June 1525 to elevate his son to the peerage and 18th June 1524 to award Bessie and her husband with a royal grant, so these events may well have tied in with the boy’s birthday.

Richmond was baptised at the chapel at Blackmore with Cardinal Wolsey acting as his godfather.

Henry Fitzroy was enobled at the age of 6 in 1525. He was given the title Earl of Nottingham first and then made the Duke of Richmond and Somerset. Suzannah Lipscombe points out that there were only two other dukes in England at this time and by giving him a double dukedom Henry VIII was making his son the highest ranking peer in the country. Other offices he was granted during his short life included Knight of the Garter, Lord High Admiral of England, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord President of the Council of the North, Warden of the Marches and Chamberlain of Chester and North Wales.

In 1527, various girls were put forward as potential brides for Fitzroy, including Mary of Portugal, the daughters of the Queen of Denmark, and even his half-sister Princess Mary, but they all came to nothing when the king became consumed with his own marriage problems. But on 26th November 1533, Fitzroy married Mary Howard, daughter of Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, at Hampton Court Palace. They were both fourteen years of age.

The wedding appears to have been rather low-key, so much so that it is not mentioned by chroniclers Edward Hall and Charles Wriothesley, and even Eustace Chapuys, the imperial ambassador, only mentions it in passing at the end of a letter to Charles V:

“I have nothing more to say, save that to-morrow the marriage of the duke of Richmond to the daughter of the duke of Norfolk is to take place.”

Fitzroy’s biographer Beverley Murphy points out that the Pope had to grant a dispensation for the marriage on the grounds of consanguinity because the bride and groom were related. Fitzroy descended from Elizabeth Woodville and Mary descended from Elizabeth’s sister, Katherine, Duchess of Buckingham. Although Chapuys’ letter appears to date the marriage to 25th November, with Chapuys saying on 24th that the marriage was due to take place “to-morrow”, the dispensation dates the marriage to the 26th.

But how did Fitzroy end up marrying Mary Howard?

Well, the Duke of Norfolk, Mary’s father, put it down to Henry VIII, commenting in December 1529 to Chapuys that “the King wishes the Duke to marry one of my daughters”, as did Mary herself in a letter to Thomas Cromwell in 1538:

“The marriage was made by his [the King’s] commandment without that ever I made suit therefor, or yet thought thereon, being fully concluded then with my lord of Oxford, which marriage would to Christ had taken effect […]”

But, as Beverley Murphy points out, “the true architect of the arrangement seems to have been Anne Boleyn”, and Mary’s mother, Elizabeth Stafford, Duchess of Norfolk, certainly blamed Anne for it. In a letter to Cromwell in 1537 regarding her jointure and that of her daughter, she wrote “Queen Anne got the marriage clear for my lord my husband, when she did favour my lord, my husband.”

In 1530, Chapuys wrote of how the duchess had clashed with Anne Boleyn because the duchess wanted Mary to marry the Earl of Derby “but the Lady Anne opposed it, and used such high words towards the Duchess that the latter narrowly escaped being dismissed from Court.” It obviously suited Anne for Fitzroy to be married off to one of her relations, rather than to a European princess. Murphy writes that “Henry’s subsequent reluctance to acknowledge the union strongly suggests that he was persuaded into it by Anne, who cannot have viewed the prospect of Richmond making a sparkling European marriage with any pleasure.”

The marriage was a political match, rather than a love match, and it is not clear how the couple felt about it or how well they knew each other. Mary had been at court for several months before the marriage serving her cousin, Anne Boleyn, but Fitzroy had been away in France for most of that time. The couple did not live together after their marriage and were not expected to consummate their union because of their youth, with Henry VIII not wanting to risk the health of his son.

Unfortunately, Fitzroy died on 22nd July 1536 at St James’s Palace. He was just seventeen years old and it is thought that his death was caused by some type of pulmonary infection, probably tuberculosis. His death was a huge blow for Henry VIII, not only because he loved his son deeply but because he was left without an heir. Henry had made both his daughters illegitimate and now he couldn’t even legitimise his bastard son. Fitzroy’s widow Mary never remarried.

Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, was originally buried at Thetford Priory, Norfolk, but his tomb was moved to St Michael’s Church, Framlingham, Suffolk. His wife, Mary Howard, was interred in the tomb after her death in 1557.

Further Reading

- Bastard Prince: Henry VIII’s Lost Son, Beverley Anne Murphy

- 1536: The Year That Changed Henry VIII, Suzannah Lipscomb