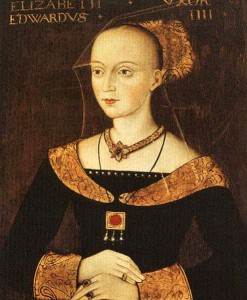

She was the daughter of a king, the sister of the Princes in the Tower, the wife of Henry VII, the mother of Henry VIII, and the grandmother of Edward VI, Mary I, Elizabeth I and James V. Her bloodline shaped the future of England, but she’s often overshadowed by the powerful men and women she was related to.

But Elizabeth was no passive figure. She was a key part of dynastic politics, and her marriage helped end the Wars of the Roses. Today, I’m exploring her remarkable life, her role in uniting the warring houses of Lancaster and York, and why she truly deserves to be remembered as the Queen of Hearts.

Elizabeth was born into a world of instability. Her father, King Edward IV, was a Yorkist king, but his throne was far from secure. The country was deeply divided by the Wars of the Roses, a long and bloody conflict between the royal Houses of York and Lancaster.

Her mother, Elizabeth Woodville, was a controversial figure. She was a commoner, and Edward IV had married her in secret, angering many of his nobles—especially his cousin and former ally, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, known as the Kingmaker.As the eldest daughter of the king, Elizabeth was an important dynastic pawn. If her father remained secure on the throne, she could be a powerful queen consort in Europe by making a good diplomatic marriage match. But in medieval England, a princess’s fate could change in an instant.

In 1470, when Elizabeth was just four, her father lost the throne. Warwick the Kingmaker turned against him and restored the former Lancastrian king, Henry VI.

Edward IV fled into exile, and Elizabeth, her mother, and her sisters took sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. It was there that her brother, Edward, the future Edward V, was born in November 1470.

For months, the family lived in uncertainty, until Edward IV returned to England in 1471, and, with his forces, entered London unopposed, taking Henry VI prisoner. Elizabeth, her mother and siblings were able to come out of sanctuary, and her father was restored to the throne after decisive victories against the Lancastrians in battle. Henry VI was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he soon died—probably murdered on Edward’s orders.

Elizabeth was once again a royal princess, and her father set about securing her future.

In infancy, she’d been betrothed to George Neville, son of the Marquess of Montagu, when her father was trying to build bridges with the Nevilles, but Montagu fighting against Edward at the Battle of Barnet in 1471 put an end to that arrangement. In 1475, when Elizabeth was nine, a French match was agreed upon. When she came of age, Elizabeth would marry Charles, the dauphin of France, son of Louis XI. However, in December 1482, France reneged on this agreement and promised Charles in marriage to the daughter of Maximilian of Austria. leaving Elizabeth’s future uncertain once again.

And then, in April 1483, disaster struck. Elizabeth’s father, Edward IV, died suddenly.

Her brother, the new king, Edward V, was just 12 years old, a boy king, which was far from ideal in a country that had been ravaged by civil war just a few years previously. However, his coronation was planned and he began his journey from Ludlow to London. His party were intercepted by his uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who took possession of the young king and arrested the boy’s other uncle, Earl Rivers, and his half-brother Richard Grey. Elizabeth, her mother, sisters and youngest brother Richard took sanctuary in Westminster Abbey on hearing news of the arrests.

Her brother, the new king, Edward V, was just 12 years old, a boy king, which was far from ideal in a country that had been ravaged by civil war just a few years previously. However, his coronation was planned and he began his journey from Ludlow to London. His party were intercepted by his uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who took possession of the young king and arrested the boy’s other uncle, Earl Rivers, and his half-brother Richard Grey. Elizabeth, her mother, sisters and youngest brother Richard took sanctuary in Westminster Abbey on hearing news of the arrests.

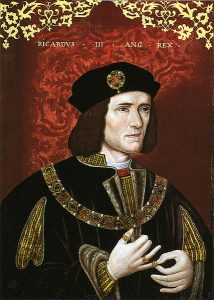

Gloucester was made Lord Protector and in June 1483, Elizabeth’s mother was persuaded by the Archbishop of Canterbury to release Prince Richard from sanctuary ready for the coronation of his brother. The two boys were taken to the Tower of London to prepare for that christening. However, later that month, Rivers and Grey were executed and Parliament declared that Elizabeth and her siblings were illegitimate and barred from the succession due to their father having allegedly been pre-contracted to Lady Eleanor Butler before his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville. Gloucester was offered the throne and became King Richard III. Elizabeth and her sisters, who were still in sanctuary, were no longer royal princesses.

Elizabeth was now a bastard, not a princess, and her once-bright future had collapsed overnight.

A plot to rescue the Princes in the Tower and to spirit Elizabeth, her mother and sisters to safety abroad came to nothing, and a rebellion by the Duke of Buckingham against Richard failed. But Elizabeth’s fate changed with a rather unlikely alliance. Elizabeth’s mother hatched a plan with Lady Margaret Beaufort, wife of Thomas Stanley, 2nd Baron Stanley, and mother of Henry Tudor, a man who was in exile and who was now the main Lancastrian claimant to the throne. At Christmas 1483, in Rennes Cathedral, Henry Tudor vowed to marry Elizabeth of York and set about planning an invasion of England.

In the meantime, Richard III took Elizabeth, her mother and her sisters out of sanctuary and brought the girls to court. This led to one of the most scandalous rumours of the time—that Richard planned to marry his niece, Elizabeth, after his wife, Anne Neville, died.

Was there any truth to it?

One dubious letter—supposedly written by Elizabeth to John Howard, Duke of Norfolk—suggests that she wanted the marriage. But the original doesn’t survive, and later versions are significantly different to each other.

Historians remain divided, but there’s no solid evidence that Elizabeth desired or supported such a match.

Richard publicly denied the rumours, but by early 1485, it didn’t matter—his time as king was running out.

While Elizabeth’s fate was uncertain, Henry Tudor was preparing to invade England. He landed on the Welsh coast on 7th August 1485 and set off marching through Wales, gathering support on the way. Richard set off with his crown forces to meet Henry, and on 22nd August 1485, their two armies met at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Richard fought courageously, but was killed. Henry Tudor and his forces were victorious, and Henry claimed the crown as Henry VII.

But he was careful. He ensured he was crowned king first—before marrying Elizabeth—so no one could say his rule depended on her claim to the throne.

Finally, on 18th January 1486, twenty-nine year-old Henry married the nearly 20-year-old Elizabeth. The marriage brought hope to the country. It reconciled the warring Houses of Lancaster and York, and began a new royal house and era: the Tudor dynasty. Medals depicting Elizabeth on one side and Henry on the other were struck in celebration of the wedding. One of the Latin phrases on the medal translated to “a virtuous wife is like a rose”.

It was a dynastic triumph, but what kind of queen was Elizabeth?Elizabeth’s main role as queen consort was to produce heirs, and she excelled in this, becoming pregnant straight away and giving birth to a healthy son in September 1486. Arthur was followed my Margaret in 1489, Henry in 1491, Elizabeth in 1492, Mary in 1496, and Edmund in 1499. Elizabeth and Edmund sadly died in childhood.

Elizabeth wasn’t as politically astute as her mother-in-law, Margaret Beaufort, and the two women shared the role on intercessor and counsellor to the king. Elizabeth appears to have been intelligent, pragmatic and well-liked, and Margaret determined, strong and experienced. Elizabeth was the Queen of Hearts, the perfect queen consort and loved by all who met her, and Margaret was the matriarch of the Tudor dynasty and a practical organiser. Quite the dynamic duo, I’m sure. Henry VII was certainly fortunate to have two such women around him.

While her eldest son was educated away from court, groomed to be king, Elizabeth was able to preside over the household of her other children, involving herself in their education. It appears that she deeply influenced her second son, the spare who would later take the throne as Henry VIII, who idolised her memory. Some believe his idealised view of women and queenship came from her example.

In 1502, Prince Arthur died, devastating both Elizabeth and Henry VII. Arthur was just fifteen. Elizabeth comforted her distraught husband and then went back to her own chamber to grieve, where she became so sorrowful that it was thought that the king would have to be sent for to comfort her.

The couple still had a spare, Prince Henry, but Elizabeth must have felt the pressure to try and provide another son. She became pregnant and on 2nd February 1503, she gave birth prematurely to a daughter, Katherine. Sadly, Elizabeth died nine days later, on 11th February 1503, her 37th birthday. Her baby girl also died.

On 23rd February, Elizabeth was laid to rest at Westminster Abbey in a lavish ceremony that cost the king £3,000. Following her death, the Venetian ambassador described her as “one of the most gracious and best beloved Princesses of the world”, and her sweet nature was often commented on in her lifetime.

Elizabeth’s death hit her family hard. A manuscript known as the Vaux Passional has an illumination on its presentation page which depicts Henry VII in the centre, two girls sitting in front of a fireplace, wearing black headdresses, thought to be Princesses Margaret and Mary, who would have been 13 and 7 at the time, and then, in the background, a black-covered empty bed with a boy with his hands on his arms, looking as if he’s weeping. That boy is thought to be Prince Henry, the future Henry VIII.

Henry VII was crushed. He never remarried, and for the rest of his life, he guarded her memory closely.

Elizabeth of York is often seen as a passive figure, but her marriage ended a war, created the Tudor dynasty, and shaped the future of England.

She was the mother of one of England’s most famous kings and the grandmother of the long-reigning Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I. And she had been the perfect queen consort. She supported her husband in all he did, acted as a mediator, intercessor and patron, put her duty to her king and country first at all times, was generous, supervised the education of her children, and sensibly never once highlighted her claim to the throne. She was dearly loved by her family and those around her, was respected by ambassadors and scholars, and also won the hearts of her people. Elizabeth of York was a true Queen of Hearts.

Her legacy as ‘the Queen of Hearts’ lives on through most modern sets of playing cards. It’s said that the stylized ‘portraits’ of the queens in card decks is based off of portraits of Elizabeth. Certainly the long lappets of her gable hood seem to be represented in the clothing of the queens. It’s an interesting theory, at any rate.