Anne Parr was born on 15th June 1515, in the early years of Henry VIII's reign. Her parents were Sir Thomas Parr and Maud Green. Thomas was an English knight, courtier, and Lord of the Manor of Kendal in Westmorland (current day Cumbria). Perhaps more famously known in contemporary historiography as the younger sister of Katherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII, Anne Parr has remained a particularly elusive character in terms of research, when compared to her fashionable contemporaries. However, she led an equally interesting and eventful life. Despite the Parr daughters having a northern-born father, they grew up in the south of England. Their father's seat at Kendal castle was, during their childhood, falling into disrepair, and living in the south was more practical in terms of their father's role at court; Westmorland simply being too far from the centre of government and monarchy. In a manner more cosmopolitan, the Parr family resided at their modest house in Blackfriars, where Anne and Katherine were likely born and raised. This relative closeness to the court was convenient for Maud Parr, who was one of Queen Catherine of Aragon's primary ladies in waiting.

Anne Parr was born on 15th June 1515, in the early years of Henry VIII's reign. Her parents were Sir Thomas Parr and Maud Green. Thomas was an English knight, courtier, and Lord of the Manor of Kendal in Westmorland (current day Cumbria). Perhaps more famously known in contemporary historiography as the younger sister of Katherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII, Anne Parr has remained a particularly elusive character in terms of research, when compared to her fashionable contemporaries. However, she led an equally interesting and eventful life. Despite the Parr daughters having a northern-born father, they grew up in the south of England. Their father's seat at Kendal castle was, during their childhood, falling into disrepair, and living in the south was more practical in terms of their father's role at court; Westmorland simply being too far from the centre of government and monarchy. In a manner more cosmopolitan, the Parr family resided at their modest house in Blackfriars, where Anne and Katherine were likely born and raised. This relative closeness to the court was convenient for Maud Parr, who was one of Queen Catherine of Aragon's primary ladies in waiting.

When Maud's husband died of the sweating sickness in 1517, she made the unconventional decision not to remarry. Instead, she dedicated the remainder of her life to the education of her children and service to the queen. As a woman of renowned intellect, Maud provided her daughter Anne with an enviable education for a female of the early sixteenth century. She employed the Humanist scholar, Juan Luis Vives, to tutor her daughters, as a result of her position as the head of the Royal school at the Tudor court, where Anne and Katherine were educated alongside other daughters of the nobility. It would be wrong to suggest that Anne received an education mirroring her male contemporaries, rather, she undertook subjects thought appropriate for the feminine condition, such as the poetry of the church fathers, classical philosophy and a fluency in romantic languages. Maud’s contemporary, Thomas More, similarly educated his children under the same, humanist syllabus. His daughter, Margaret, undertook classical studies and became a leading figure of feminine education. As historian Linda Porter states, Anne would have accessed, critiqued and studied similar works of the classical greats, including Plutarch, Cicero, & Plato; alongside contemporary sixteenth-century humanists, such as Erasmus.

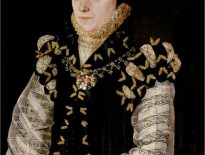

Much of Anne’s life between the years 1528-1538 are poorly documented, when compared to her sisters. However, in 1528 her mother had secured a position at court for youngest daughter as a maid-of-honour to Queen Catherine of Aragon. By this time Anne was thirteen, the appropriate age for a young, impressionable girl to enter court life. Evidently, Anne must have been an attractive and suitable candidate, as only the most exceptional of young, aristocratic girls were permitted to serve the queen at court. To support this, a portrait thought to be Anne Parr in her twenties or thirties, by Hans Holbein the Younger, reveals an attractive woman with light blonde hair and well-shaped lips, in a fashionable black bonnet. During the 1530s Anne retained her position at court, attending on Henry VIII's successive wives. Historian Anthony Martienssen argues that it was the result of Queen Anne Boleyn's influence that resulted in Anne's involvement in the Protestant cause. Whether this is the case, both Parr daughters became resilient religious reformers and associated themselves with other likeminded women at court, such as Charles Brandon's wife, Catherine Willoughby. Unlike her sister, Katherine did not engage herself with court life to the same extent until the death of her second husband, Lord Latimer. Rather, she made a series of childless marriages in the northern part of England. Upon Katherine's introduction into London society, Anne would have been a good source of introduction for her elder sister, having served at court for fifteen years by the time of Latimer's death in 1543.

William Herbert

The Parr family’s status changed dramatically in 1543 when Anne’s sister was married to Henry VIII of England; becoming his sixth consort. Anne’s position transformed from courtier’s wife to the honourable sister of the queen. With such a distinguished position, Lady Herbert (as she would have been titled upon her marriage) was present at the queen’s intimate wedding ceremony performed at Hampton Court Palace on 12th July 1543. Throughout the 1540s her status continued to rise, as her husband was knighted on the battlefield at the Siege of Boulogne during the king’s campaign against the French. Anne became Katherine’s chief lady in waiting at court, and the sisters indulged in educational studying; reading, discussing and patronising artists, academics and poets. Significantly, Anne patronised the Humanist scholar, Roger Ascham. This is primary evidence that Anne continued her childhood love of learning into later life as Ascham, writing from Cambridge in 1545, told Anne that, ‘at last, I send you your Cicero, most noble lady; since you are delighted so much by his books, you do wisely study them’. It was during the queen’s tenure that Anne became the chief member of the intimate Protestant circle of women at court that surrounded the queen; engaging in reformist religious debate in the queen’s private apartments. Alongside these educated women, Katherine was influenced to read and write theological works in the reformist fashion. She anonymously published her pieces entitled: Prayers or Meditations and Lamentatiosn of a Sinner, both emphasising her evangelical faith through biblical scripture and a personal relationship with God.

As a result of Katherine’s endeavours at court she gained a substantial number of enemy’s intent on her downfall; additionally, as a result of her growing influence with the king. These included: Stephen Gardener, Thomas Wriothesley and Richard Rich. This group of conservative men lobbied for the king’s support in denouncing Katherine as a heretic, stressing that her chambers stored forbidden books and that she and her ladies were organising the king’s ‘destruction’. As John Foxe tells it (his account was written after the events and was particularly dramatic as a result of his Protestant sympathies), the conservative faction believed Katherine to be a genuine threat, and that her highness was influenced domestically by her scheming women, particularly three women: The queen’s sister, Anne; Lady Lane, her cousin; and Lady Tyrwhitt. Foxe continues that ‘it was devised that these three should first of all have been accused and brought to answer to the six articles (put forward in 1539), and upon their apprehension in the court, that their closets and coffers should be searched.’ Essentially, these men intended to find any incriminating material they could in order to advance their cause of disgracing Katherine from Henry’s affection. Luckily for Katherine, she cleverly fell on the king’s mercy and was ultimately forgiven, much to the dissatisfaction of the conservatives.

Anne’s employment did not end upon the king’s death on 28th January 1547, instead, she and her children resided at the now queen dowager’s house at Chelsea and were part of the household there. Lord Herbert was appointed one of the guardians of the new king and was an initial supporter of the Seymour protectorate. Once the former queen Katherine had died of childbed fever in September, Lady Herbert soon began service as one of the ladies in waiting to the Lady Mary, future queen of England. The end of Henry’s reign did not cease the future successes of the Herbert family, as they continued to rise in status during the initial years of the 1550s. Anne’s husband was created Earl of Pembroke on 11th October 1551 and received the disgraced Duke of Somerset’s Wiltshire estates, alongside extensive woodland on the borders of the New Forest. Unfortunately for Anne, she died on 20th February 1552. The cause of her death is unknown; however, she was thirty-six years of age at her death, a similar age to that of her elder sister Katherine when she died in 1548. The Countess of Pembroke was buried on 28th February 1552 in the Old St Pauls Cathedral. When her husband died on 17th March 1570, he was interred next to her. Anne’s memorial, described in Latin, states that she was ‘a most faithful wife, a woman of the great piety and discretion’. This is not a particularly unusual epitaph, rather, sixteenth-century memorial inscriptions, for women, often promoted their mortal virtues and devoted life to service.

By Alexander Taylor

Picture: An unknown lady, possible Anne Parr, by Hans Holbein the Younger

Leave a Reply