Anne of Cleves was born on 22nd September 1515 in Dusseldorf to John III, Duke of Cleves, and his wife, Maria. Like Henry VIII’s first wife, Katherine of Aragon, Anne was born into a highly influential and politically active family. Her sister Sybille was married to the Elector of Saxony, and her brother, Wilhelm, became the future Duke of Cleves-Burg, and would be instrumental in negotiations regarding her future marriage.

Anne of Cleves was born on 22nd September 1515 in Dusseldorf to John III, Duke of Cleves, and his wife, Maria. Like Henry VIII’s first wife, Katherine of Aragon, Anne was born into a highly influential and politically active family. Her sister Sybille was married to the Elector of Saxony, and her brother, Wilhelm, became the future Duke of Cleves-Burg, and would be instrumental in negotiations regarding her future marriage.

Anne was born during the volatile reformation period, resulting in reforms against traditionalist Catholicism, which was spreading through western and northern Europe. Her mother has been described as a conservative Catholic, however, her sister Sybille’s husband was a renowned Lutheran, often given the epithet ‘champion of the reformation’, and a good friend of its founder, Martin Luther. Anne was originally intended to be married into the House of Lorraine when she was eleven in 1527. There were numerous negotiations regarding the union, but nothing was cemented, and by 1535 all official wedding discussions had essentially been rejected, leaving the desirable duke’s daughter available on the European marriage market. Henry VIII and his council were searching for a new wife after the death of Queen Jane Seymour in 1536, with rumours of a possible union with the Duchess of Milan. The French had aligned themselves to the Habsburgs and signed a ten-year truce in 1538 (although this never lasted), cementing a union between Europe’s two major Catholic powerhouses. Cromwell, Henry’s leading minister at the time, suggested a counter alliance with a Lutheran house in Germany, even though Anne’s family were relatively mild in their reformist views. Cromwell was aware that England was potentially vulnerable to a Franco-Habsburg invasion, and influenced the king that negotiating with the newly appointed Duke Wilhelm (Anne’s father had died in 1539) would be a successful diplomatic adventure, that would ensure the prosperity of England against foreign invasion.

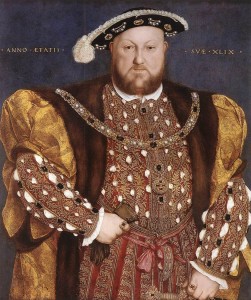

Throughout history, the discussion of Anne’s appearance has divided historians and caused thorough debate. John Hutton, the ambassador to Mary of Hungary, Regent of the Netherlands, stressed that none ‘praised her beauty’ however, most historians have proved this to be an unreliable source, with the statement likely the response of hear-say. Upon discussions, and with Henry’s consent, Nicholas Wotton and Richard Beard were sent to negotiate a deal with Duke Wilhelm. Renowned artist Hans Holbein the Younger travelled to Wilhelm’s court with the instruction to paint both Anne and her sister Amalia. Cromwell had informed the king on behalf of Anne’s appearance that..’Every man praiseth the beauty of the same lady as well for the face as for the whole body… she excelleth as far the duchess [of Milan] as the golden sun excelleth the silver moon.’ Henry was adamant that Holbein should paint Anne realistically, and Wotton swore the portrait was an honest portrayal. It has commonly been believed that Anne was referred to as ‘the Flanders mare,’ however, this term was, in fact, the writing of a seventeenth-century bishop, named Gilbert Burnet, writing some one hundred years after the princess’s death, therefore having no contemporary opinion of her beauty. Her portraits, including the miniature sent to Henry, show a highly attractive woman.

With negotiations settled and Duke Wilhelm’s approval, on 26th November 1539 Anne of Cleves embarked on her journey to England. Her mother Maria was not overly fond of the union, likely the result of Henry’s previously failed marriages, with his second ending in an execution that shocked even the most conservative of Europe. Anne arrived in Rochester on 31st December the same year, after a tiring journey, which was delayed by violent storms. In reference to Anne’s comparison with a horse, popular history repeats the story that Henry was repulsed by her unappealing appearance. However, upon her arrival, the jovial Henry had decided to surprise the soon to be Queen of England, dressed in disguise. The repercussions of this event made for a disastrous first impression, with Anne and her German speaking entourage horrified at Henry’s brash and uncivilised gesture. It is important to note that Anne had not received the kind of education in court culture as her predecessors had, she was no sparkling Renaissance princess from the fashionable English or French courts, and was not raised with the importance of perfecting her singing or dancing skills. Wotton’s report to Cromwell regarding Anne supports this, stating.. ‘She occupieth her time most with the needle, she cannot sing, or play any instrument, for they take it here in Germany for a rebuke and an occasion of lightness that great ladies should be learned in music.’ Anne’s lack of dutiful response has led historians to believe that this event highly affected Henry’s egotistical personality. She had not responded as expected, as Katherine of Aragon had done in earlier instances of Henry’s juvenile acts of courtly humour. Historian Lady Antonia Fraser has stated in her research that..’In 1538 Henry VIII wanted - no, he expected - to be diverted, entertained and excited. It would be the responsibility of his wife to see that he felt like playing the cavalier and indulging in such amorous gallantries as had amused him in the past.’ Therefore, as a result of this unfortunate meeting, the king’s feelings for Anne never manifested into anything other than disappointment and repulsion.

Once the royal couple were married on 6th January 1540, at Greenwich, issues of consummation soon became apparent. Henry complained to Cromwell on several occasions that he was unable to sexually perform, as a man should be able to with his wife. He found her in a ‘manner undesirable and unpleasant’ and put the blame firmly on Anne rather than himself, who was by now almost fifty years old; suffering from a sore and vulgar leg ulcer. The Earl of Rutland was given the task of encouraging Anne to act ‘more pleasantly towards the king,’ in order to provoke some lust into their marriage. However, she believed the union to be prospering; having written to her family in Germany that she was content with her situation. A few days after the royal wedding, a celebratory tournament was held at Greenwich. The contemporary chronicler, Edward Hall, recorded the event and praised the German princess, stating..’She was appareiled after the English fashion, with a French hood, which so set forth her beauty and good visage, that every creature rejoiced to behold her.’ Clearly, Anne was acclimatising to English culture and customs; therefore from an outside perspective, it can be argued that the queen was contently immersing herself in her new role as queen consort, merrily playing cards and settling into court life. The queen had reportedly confided in her ladies in waiting, including Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, that..’When the King comes to bed he kisses me and taketh me by the hand, and biddeth me good night... In the morning he kisses me, and biddeth me, farewell. Is not this enough?’ Anne was firm in the belief that she was in favour with the king, and presents a sense of juvenile naivety in terms of a queen consort’s primary role as childbearer. Further attempts were made to try and get Anne to provide the king with further affection, but relations between the two failed to increase, and Henry’s eyes were beginning to focus on someone else.

Once the royal couple were married on 6th January 1540, at Greenwich, issues of consummation soon became apparent. Henry complained to Cromwell on several occasions that he was unable to sexually perform, as a man should be able to with his wife. He found her in a ‘manner undesirable and unpleasant’ and put the blame firmly on Anne rather than himself, who was by now almost fifty years old; suffering from a sore and vulgar leg ulcer. The Earl of Rutland was given the task of encouraging Anne to act ‘more pleasantly towards the king,’ in order to provoke some lust into their marriage. However, she believed the union to be prospering; having written to her family in Germany that she was content with her situation. A few days after the royal wedding, a celebratory tournament was held at Greenwich. The contemporary chronicler, Edward Hall, recorded the event and praised the German princess, stating..’She was appareiled after the English fashion, with a French hood, which so set forth her beauty and good visage, that every creature rejoiced to behold her.’ Clearly, Anne was acclimatising to English culture and customs; therefore from an outside perspective, it can be argued that the queen was contently immersing herself in her new role as queen consort, merrily playing cards and settling into court life. The queen had reportedly confided in her ladies in waiting, including Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, that..’When the King comes to bed he kisses me and taketh me by the hand, and biddeth me good night... In the morning he kisses me, and biddeth me, farewell. Is not this enough?’ Anne was firm in the belief that she was in favour with the king, and presents a sense of juvenile naivety in terms of a queen consort’s primary role as childbearer. Further attempts were made to try and get Anne to provide the king with further affection, but relations between the two failed to increase, and Henry’s eyes were beginning to focus on someone else.

After six months of marriage, Henry decided to begin negotiations for an annulment. Anne complained that the king was doting on one of her ladies-in-waiting, the petite and pretty Katherine Howard. The king was believed to have used the cover of publicly announcing that the annulment was the result of being in a state of uncertainty regarding Anne’s right to marry, as the relevant documents from Cleves had not arrived regarding her previously arranged union with the House of Lorraine. Of equal importance, was that the Royal couple’s private life had not improved during their short six-month marriage. Historians have stressed that the king was generally repulsed by her body, or that he was psychologically distressed at the thought she may have been a previous man's wife. Anne was distraught at the thought of a separation. On 6th July, when a delegation of councillors sought to inquire about the union, she suddenly felt weak and was believed to have fainted, and upon composing herself, refused to cooperate with the demands of the delegation. Understandably, she was distressed; and the events of the day must have affected her pride vastly. Although believed to be ‘Henry’s luckiest queen’ she, at the time, felt embarrassed and saddened by the situation. After convocation had declared the union invalid on 9 July, Anne had no other choice but to accept the demands and accept the situation. Although a short-lived union, which produced no heirs nor political security; Henry ensured that his fifth wife was given a handsome and comfortable settlement. This included an allowance of 8,000 nobles for her newly appointed household away from court, with the use of the Palaces of Richmond and Bletchingley Manor. She also became an honorary member of the Royal Family, as “King's Right Dear and Right Entirely Beloved Sister”, taking precedence of all women attending court, minus the king’s future spouse and their children.

Anne’s retirement was comfortable for the remainder of Henry’s reign. She was honoured with several visits to court in 1543 and 1546 and was formally introduced to the king’s new wife, (one of her previous ladies) Queen Katherine Howard, during the festive period of January 1541. The two dined with Henry and contemporaries commented that once the king had retired to his chambers, the two ladies danced merrily together. The following day Katherine transferred to Anne two of her New Year’s presents, which included a small ring and two dogs - a display of Katherine’s warmth and acceptance of Anne’s position as the king’s beloved sister. Rumours began to circulate during the aftermath of the young queen’s controversial downfall that the former queen had inquired into remarriage with the king, however, these unsubstantiated rumours came to nothing, and Henry married Katherine Parr in 1543. Henry granted Anne further manors, including Hever, the childhood home of his second wife, Anne Boleyn, and she was kept in comfortable conditions until the king’s death in 1547. Her life under the former king’s children was marred by animosity with her servants and a lack of continuity in her living conditions; having her residence of Richmond confiscated. Initially happy in England, with the embarrassment of returning to Germany after a failed marriage too humiliating to bear, Anne made several pleas to her brother for financial security, however, these interventions failed to provide her with much relief. The former queen remained on good terms with Queen Mary throughout her reign, and attended her coronation with the Princess Elizabeth for her final public appearance in 1553, before retiring to her Kentish estates.

Anne of Cleves died on 16th July 1557 at Chelsea old Manor, aged 41. Reports state she had been feeling somewhat ill during the spring of that year. Her cause of death is unknown, however, Lady Antonia Fraser has suggested cancer as a potential cause. Anne was the only one of Henry’s six wives to be honoured with a burial fit for a woman of her status, in Westminster Abbey. None of Henry’s other five wives was given this privilege, not even the royal Katherine of Aragon, who now rests in Peterborough Cathedral.

By Alex Taylor

For someone who could be so hardhearted by having two of his wives executed, it makes me wonder why, if Henry suspected that Anne of Cleves might have been married before and he was repulsed by her, he made her his “sister” and treated her as well as he did after the annulment. Going by her portrait, she was attractive enough and I wonder if Henry ever considered that a woman’s response to him might not always be sublime. In the article, it reminds us that Henry was an enormous man by this time and the ulcer on his leg must have been badly infected which would have caused an unpleasant odor all its own. He complained about Anne having an odor, but he had little room to talk. I guess it’s a matter of the times and the fact that the king was the King and a wife didn’t complain or give constructive, kind advice. If only we knew that it could have been Anne who might have borne him a healthy son!

It’s so sad how he treated Anne when she seems to have been such a lovely lady who did all she could to be a good queen. I think Henry just felt that he was king, God’s anointed sovereign, and that he was special and there couldn’t possibly be anything wrong with him; it must all be Anne’s fault. They got on so well afterwards, and she got on well with his children too, so I’m sure that given time the marriage would have been a successful one.