Ambrose Dudley was born the fourth son of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, and his wife, Lady Jane Guildford. Ambrose came from an exceptionally large family; he had twelve siblings. The family were renowned for their Protestant zeal: Ambrose’s sister, the Countess of Huntingdon, promoted her Protestantism by opening a school in the north of England for young gentry women. Among her pupils was Lady Margaret Hoby, a noted diarist whose pious daily accounts survive to this day. Much of her diary reflected her strict, daily, religious observances, with little information regarding her personal life. Similarly, Ambrose’s father was a prominent reformer during the reign of Edward VI. He was ultimately executed for his involvement with promoting Lady Jane Grey as queen through lobbying the ailing king Edward VI for support; in violation of the former king Henry VIII’s decreed will.

Ambrose Dudley was born the fourth son of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, and his wife, Lady Jane Guildford. Ambrose came from an exceptionally large family; he had twelve siblings. The family were renowned for their Protestant zeal: Ambrose’s sister, the Countess of Huntingdon, promoted her Protestantism by opening a school in the north of England for young gentry women. Among her pupils was Lady Margaret Hoby, a noted diarist whose pious daily accounts survive to this day. Much of her diary reflected her strict, daily, religious observances, with little information regarding her personal life. Similarly, Ambrose’s father was a prominent reformer during the reign of Edward VI. He was ultimately executed for his involvement with promoting Lady Jane Grey as queen through lobbying the ailing king Edward VI for support; in violation of the former king Henry VIII’s decreed will.

While the Dudley family’s religious convictions were well established during the 1550s, little is known of Ambrose’s early years and those of his siblings. Little surviving evidence remains that mention where he spent his childhood years, what subjects he studied or who he was taught by. However, historians have suggested that Ambrose, and his brothers, were taught by the mathematician (later astrologer under Queen Elizabeth I) John Dee. The Dudley boys likely undertook a similar humanist education to their noble, protestant contemporaries, such as Lady Jane Grey, who studied the great writers of antiquity, including Plato, Cicero and the early Church fathers. Ambrose’s early career began in 1549 when he was around the age of nineteen or twenty. He is recorded as serving with his father against the Norfolk rebels, now commonly referred to in historiography as ‘Kett’s rebellion’. However, historians have argued that the revolt was not mutually exclusive with previous Tudor rebellions, such as the religiously motivated Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. Rather, Kett’s rebellion was in response to land enclosures and occurred as a result of agricultural grievances rather than the religious changes decreed by the Edwardian government.

In terms of Ambrose’s personal life, he married, as his first wife, Anne Whorwood, daughter of William Whorwood. Unfortunately for Ambrose, this was a short-lived marriage as Anne reportedly died of the sweating sickness in May 1552. The couple did, however, produce one child together; a daughter named Margaret, (this is disputed) however, she died shortly after birth. Ambrose’s second wife, Elizabeth Tailboys, 4th Baroness Tailboys of Kye, provided Ambrose with a more substantial marriage. They were married for a decade, and the marriage appears to have been fulfilling, excepting the lack of children. (The Baroness reportedly suffered a phantom pregnancy in the mid-1550s) Lady Dudley died in 1563, again leaving Ambrose a childless widow. He took as his third, and final, wife Anne Russell. The ceremony took place on 11th November 1565 in the chapel royal at Whitehall Palace. The wedding was a notably lavish affair, which included elaborate tournaments and banquets. Additionally, the union united two significant Protestant families of high Tudor society: the Russells and the Dudleys.

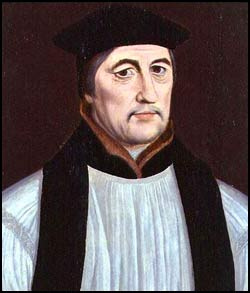

Ambrose’s life changed considerably as a result of his participation in the Lady Jane Grey affair. He, along with the rest of the Dudley family, and in affiliation with the Grey family, were staunch opponents of the reintroduction of Catholicism that would have resulted from Princess Mary Tudor ascending to the English throne. In July 1553, with Mary marching on London from her headquarters in East Anglia, Ambrose and his father surrendered at Cambridge. Following their defeat, they were arraigned together with two of Ambrose’s brothers: Henry and Guilford. It was around this time, specifically in 1554 when Ambrose was still in the tower, that Lady Dudley proved herself to be an astute and competent ally of her husband’s family. She lobbied Roger Ascham, a leading scholar of the period, to ensure her husband’s release. Her endeavours were fruitful, for in December of 1554 Ambrose had been released and joined his brother, Robert, in the tournaments arranged by Philip of Spain (Queen Mary’s Spanish husband) to cement Anglo-Spanish relations. Queen Mary was ultimately a benevolent, but vigilant, queen who forgave those who supported the Grey/Dudley faction; Frances Grey, Lady Jane’s mother, lived under the watchful eye of the queen up until her death in 1559.

It was with the Elizabethan era that Ambrose’s future improved. In March 1559 he was granted the manor of Knebworth Beauchamp, Leicestershire, and the office of Master of the Ordnance. Additionally, during the early 1560s, Ambrose was granted several more privileges, including the lordship of Warwick, a series of castles and the Barony of Lisle. Evidently, the now styled Lord Warwick was reaping the benefits of serving under a Protestant monarch; her relationship with Warwick’s brother, Robert, helped cement good relations between the Dudleys and the royal family. Lord Warwick was also able to demonstrate his military prowess through the expeditionary force to Newhaven (Le Havre) in France in 1562. While the situation was challenging regarding the religious factionalism, Elizabeth was content with Warwick’s work at intervening to the best of his capabilities, with his return to England deemed honourable. Sadly, for Warwick, upon his return to England, his wife died. His next marriage to Anne Russell, then aged sixteen, was deemed potentially inappropriate but, as stated earlier in this article, the unification of two Protestant houses overshadowed any doubts of Anne being too young for Lord Warwick.

The remaining two decades of Lord Warwick’s life were successful, and he received a post on the privy council on 5th September 1573. While he was initially active and participated in council meetings regularly, records show that his attendance began to decline during the latter end of the 1570s. There are several possibilities for this decline: firstly, Warwick was known for his enjoyment of private, country life, specifically at his house of North Hall in Hertfordshire, and secondly, that his ailing health prevented him attending. While Lord Warwick was evidently the less glamorous and awe-inspiring Dudley brother, when compared with the charismatic and vivacious Earl of Leicester, the brothers did enjoy an affectionate relationship. This is hardly surprising following the tumultuous events that took place in the early 1550s; resulting in the execution of the Dudley patriarch and his son, Guildford. Leicester and Warwick, on several occasions during the reign of Elizabeth I, went on progress together and made visits to the Midlands. Additionally, the brothers wrote affectionate letters to each other, emphasising their brotherly bond and shared interests.

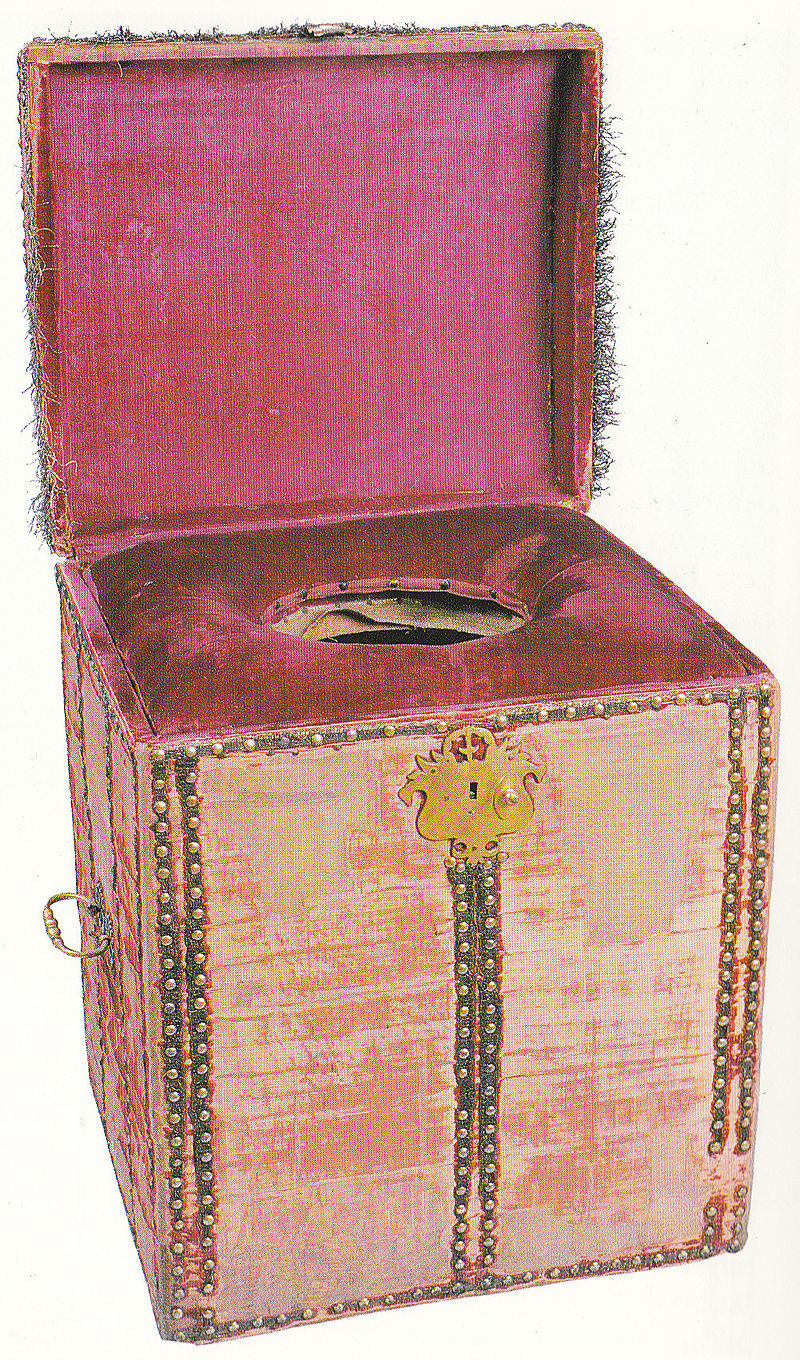

During Lord Warwick’s later life, the Dudley family grew smaller as a result of the deaths of his siblings: Lady Mary Sidney died in 1586, followed by the Earl of Leicester in 1588; much to the sadness of the queen who lamented his death for the remainder of her life. By the time of Leicester’s death, Warwick and his sister, the Countess of Huntingdon, were the last remaining Dudley children alive. Warwick made his own will on 28th January 1590, just before the amputation of his leg; this was the result of a wound he received during his campaign in Newhaven during the earlier years of the queen’s reign. His will decreed money to his wife and the use of North Hall for the remainder of her life, including items left to his sister. Lord Warwick died at Bedford House on 21st February 1590. His funeral took place on 9th April, and like Leicester, he was buried with all due pomp and ceremony, befitting his position as a leading magnate of the period. During his mortal life, Warwick gained a reputation as the ‘Good Earl of Warwick’. Although a rather affectionate sobriquet, there is little evidence to suggest that Warwick was a particularly charitable benefactor, nor was he known for his outward kindness.

by Alexander Taylor

Here is a photo of Ambrose Dudley's tomb in the Beauchamp Chapel of the Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick. You can click here to read more about his death and to see more photos of the chapel.

Leave a Reply